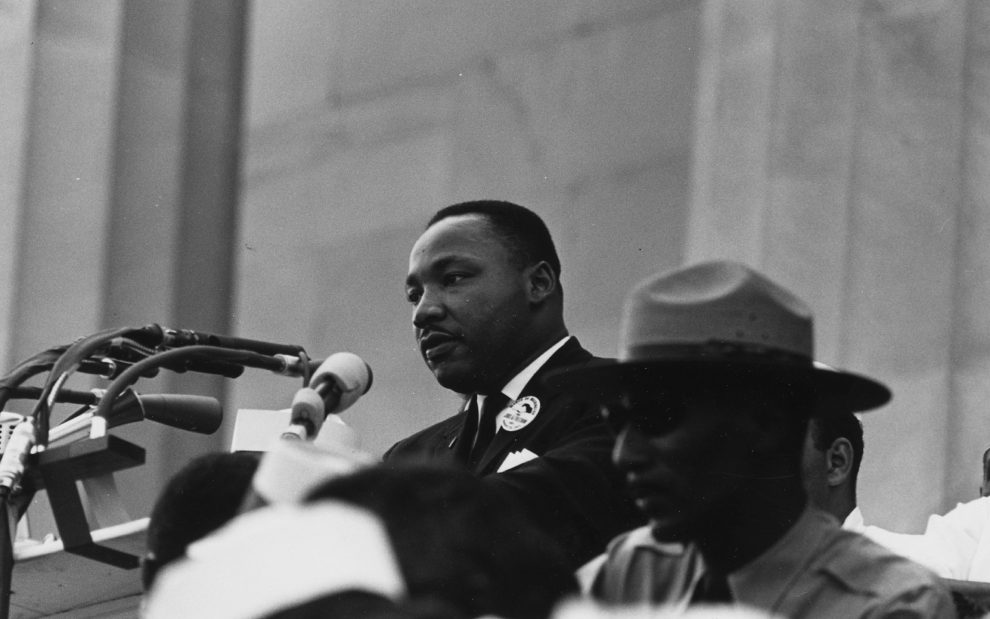

Sixty years ago, on August 28, 1963, a young Black minister addressed what was the largest assembly of civil rights protesters in the nation’s history. He recounted the country’s legacy of broken promises over racial equality, which he described as checks returned marked “insufficient funds.” He described the “great trials and tribulations” that so many had endured: harassment, beatings, and the horror of being crammed in dank, narrow jail cells for their convictions. Yet he implored them to continue their grinding, treacherous, and dangerous work for justice: “Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to South Carolina, go back to Georgia, go back to Louisiana, go back to the slums and ghettoes of our northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed.” And then, at the urging of a gospel singer, Mahalia Jackson, he shared a dream: a litany of inspirational visions of what one day will be because of what they dared to do now. Martin Luther King Jr. dreamed while Black.

People study King’s landmark “I Have A Dream” speech as a masterpiece of public religious discourse. The speech is a powerful melding of the highest aspirations of the nation’s ideals with the Judeo-Christian tradition’s prophetic conviction of the equal human dignity of all people, without exception.

And yet, today the radical force of this seminal address is often diluted and suppressed. Most know only the final three minutes of this 20-minute speech. Many of us can recall King’s hope that his children will one day live in a country where they will be judged by their character not their skin color. But few know the searing critique that preceded his expression of hope. We pass over his denunciation of a nation whose deeds rarely match its professed creeds and whose commitment to justice for Black and poor people is too often tepid, anemic, and half-hearted at best. We forget his scathing criticisms of those who would settle for a false peace that suppresses the terrible realities of inequitable housing, employment, education, and health care.

Our memory of King is selective. Jonathan Eig, in his recent biography of King, observes that people hear of his dream of universal brotherhood but not his call for “fundamental change in the nation’s character, not his cry for an end to the triple evils of materialism, militarism, and racism.”

In a growing number of places, King’s speech and especially his later writings cannot be taught in public schools. His uncompromising critique of the nation’s deeply embedded structural racism is rejected as a form of “critical race theory”—which is the label some give to any racial analysis that makes too many white people uncomfortable.

In our Western culture, with our overly rational educational systems, we tend to disparage dreams and visions as being impractical. We dismiss them as idle distractions. But I have long been obsessed with the power of the human imagination, especially the imagination of the despised, disdained, and stigmatized. I am inspired by how, despite all that they have been through and still endure, people dream of new worlds. We persist in the hope that reality not only should—but will—be other than it is. Dreams are what propel people to do risky and dangerous things for the sake of justice.

Anniversaries are times of remembrance and rededication. We must remember King more fully and accurately. He summons us to dare to dream boldly, audaciously, even subversively. For in the face of ongoing wars, xenophobic nationalisms, and anti-Black violence, we don’t need less imaginative hope. The need for animating visions, sustaining dreams, and motivating imaginations is more, not less, urgent.

Like King, we must dream of and work for a world animated by true Christian love for all, especially the least among us. As he said in 1967, near the end of his life, “I still have a dream, because, you know, you can’t give up in life. . . . I still have a dream that one day justice will roll down like water, and righteousness like a mighty stream. . . . I still have a dream today.”

This article also appears in the September 2023 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 88, No. 9, pages 40-41). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Archives.gov/Rowland Scherman

Add comment