One thing I didn’t expect about working at a parish named Our Lady of Sorrows was the frequency with which friends, acquaintances, and strangers, upon hearing the name of my place of employment, were perplexed or perturbed.

“Our Lady of what?!” they’d exclaim.

“That’s a bit dark,” they’d wince.

The people who were unfamiliar with this particular devotional title for Mary—non-Catholics and Catholics alike—found the name gloomy and unsettling, to say the least. I was always quick to give this way of knowing Mother Mary a positive spin.

While I agree that Our Lady of Sorrows lacks the uplift of some of Mary’s other monikers—say, the Queen of Heaven or Mother of Mercy—I find the meaning behind the title both interesting and comforting. Our Lady of Sorrows is one of Mary’s names because the gospels record seven sorrows in her life: the prophecy of Simeon in the Temple that a sword would pierce her soul; the flight into Egypt to protect her child from murder; the loss of child Jesus in the Jerusalem Temple; her walk with Jesus on the way to Calvary; Jesus’ crucifixion and death; his removal from the cross; and finally, his burial.

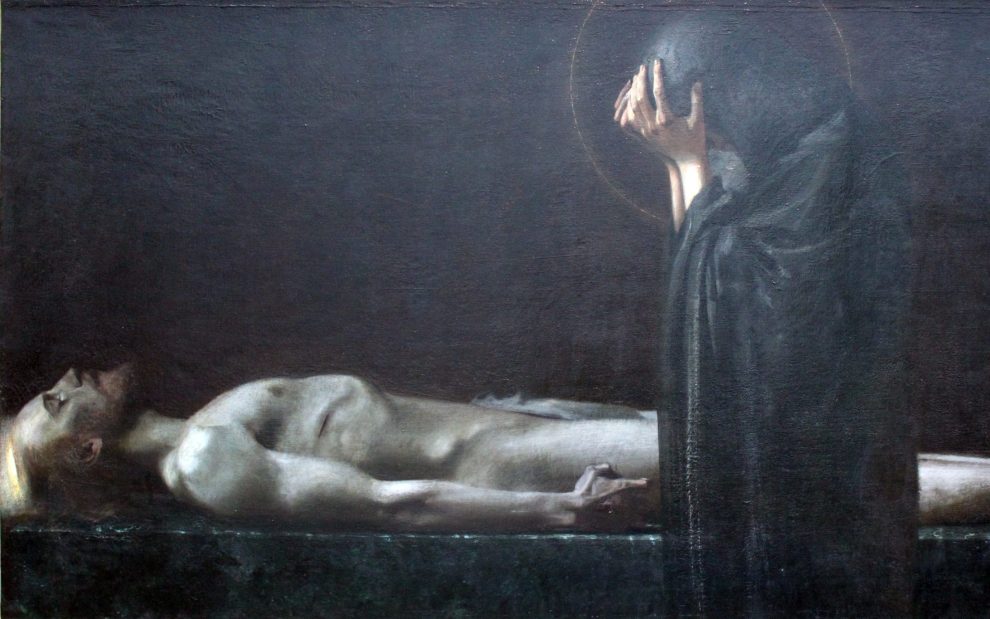

These sorrows have become a popular theme in religious art. (A common image is that of Mary being pierced by seven swords.) Michelangelo’s Pieta, a statue housed in St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City, is a portrayal of Mary’s sorrow over her dead son; visitors to the statue are themselves often moved to sorrow as they are drawn into the sculpted depiction of Mary’s agony.

While Mary is often shown in tears or wearing a sorrowful expression, that doesn’t make this aspect of her nature inherently dark or dour. Rather, I find Our Lady of Sorrows to be a validating and resonant image for modern parents and caregivers.

Call me Debbie Downer, but I find something inherently sorrowful about being a parent. I know I’m not alone when I say the love I feel for my children has an intensity that’s beautiful and wonderful, yes, but also utterly terrifying. Let’s put it this way: if I peek in on my babies when they’re fast asleep in their beds with peaceful expressions on their chubby faces, the sensation I feel is more akin to a punch in the gut than a warm wash of rainbows and butterflies. My husband and I often say to each other, “They are too good for this world.” It’s true, and thinking of the decades (hopefully) they will spend on this damaged planet makes me sad and scared, both for them and for myself. In the words of C.S. Lewis, “To love at all is to be vulnerable. Love anything and your heart will be wrung and possibly broken.”

Sure, most of us won’t have to watch our sons endure a brutal and unjust execution, as Mary did, but our children’s inevitable pain, of one sort or another, will wring our hearts. Suffering is an inescapable aspect of being a human on this Earth, and being a parent means we will witness our children’s physical and emotional anguish. At best, their pain will be the standard fare of growing up: vaccines and skinned knees, social and romantic rejections, disappointments at school and work, maybe a broken bone or two along the way. At worst, our children may encounter life-altering diagnoses, serious motor vehicle accidents, emotional traumas, and random disasters, all beyond our protection. Either way—at best or worst—I’m filled with dread when I consider the trouble my children will inevitably face in life.

The sorrow I will experience alongside my children’s pain has no antidote—but Our Lady of Sorrows offers a gentle and merciful reminder that we are not alone as we travel these darker roads of the parenthood journey. She, too, traveled them, two thousand years ago.

Beyond the comfort of camaraderie, Mary provides more practical help as well. The stories of her seven sorrows offer us guidance and wisdom as we react to our own children’s suffering. When witnessing the pain of our children—and anyone we love for that matter—we are often tempted to try to “fix” the situation by removing the cause of suffering. Or we may offer our children advice we feel will help them avoid or alleviate their pain. We may seek to minimize their pain by encouraging them to “see the bright side.” And when we see our child struggling with a task, most of us parents have had to bite our tongues or walk away in order to keep ourselves from intervening.

It’s excruciating to watch someone we love having a hard time, and our impulse to try to “make it better” isn’t inherently wrong. The problem is that our interventions often don’t actually remedy anything. (Being told they’re better off without the ex-boyfriend or -girlfriend, for example, doesn’t lessen the sting of rejection.) Even if we can reduce our children’s suffering, our involvement might undermine the development of their own resilience and problem-solving skills.

Of course, there will be plenty of times when we will intervene in our children’s lives to help them. Heck, I’m 34, and my mom still hems my jeans and helps me navigate various perplexing aspects of adulthood. But our parental interventions should look more like accompaniment as our kids face struggles, and helping them figure out creative ways to be resilient, rather than shielding them from hardship. Like Mary walking beside her son to Calvary, we can go with our children through the hard times they face—but we can’t carry their crosses for them. Children must learn to face life’s disappointments and challenges, while we parents must learn to endure the pain we feel when seeing theirs.

Our Lady of Sorrows provides an excellent example. She doesn’t flee from Jesus’ suffering at Golgotha but stands with him through it. She doesn’t yell at the Roman soldiers, protesting injustice on her son’s behalf, but trusts his decision to submit to authority. And because she accepts both her son’s sorrow and her own, she can be attentive to him through it, offering him the true gift of a calm, loving, and gentle presence.

May we learn from Our Lady of Sorrows how to give such a presence to our own children—and may we ourselves receive it from Mother Mary.

Image: Wikimedia Commons/Franz Stuck, Pietà, 1891

Add comment