The first sign that something was wrong was at the luncheon following my father’s memorial Mass at St. Gregory the Great Church in Chicago in February 2020. In conversation with friends, the subject of the new virus/flu was broached. One friend said he wanted to bring his daughter home from school in Europe due to increased anxiety over the fast-moving epidemic. Being neither a husband nor a father, I took a cavalier attitude and uttered a Churchillian sort of “keep calm and carry on.”

Two weeks later things went from Churchillian to Orwellian as the Archdiocese of Chicago, in concert with city, state, and federal officials, shut everything down. Within months, COVID-19 had exploded into a global pandemic with no foreseeable cure. For that first dystopian year, it seemed the Earth itself was dying.

My studio at St. Gregory, where for 20 years I wrote and painted as an iconographer and artist in residence, had always been an epicenter of artistic frisson with workshops, classes, tours, exhibits, and my own work creating icons. Now it was empty and silent. Even my iconography, through which I tried to bring light and hope to others, seemed superfluous with millions dying from COVID-19 and millions of others unable to work. What the world needed was medicine, food, and cures—not icons.

My pastor, Father Paul Wachdorf, and pastoral minister, Deacon Paul Spalla, brought me back to my vocational obligations. During that vertiginous year of lockdown, both came to their offices every day. Father Paul emailed homilies and reflections, called parishioners and staff, and, when allowed, visited the sick and prayed with the dying. Deacon Paul called the sick and elderly daily and left groceries on their doorsteps.

Their calm commitment to their vocation was a potent counterpoint to my hopelessness and hysteria. They showed me that even during a global pandemic, mission and ministry are nonnegotiable obligations in a vocation.

Buying panels and supplies with which I could create my icons, however, was a luxury of the past. With many companies declaring that deliveries would take four to six weeks, if they came at all, I was introduced to a new phrase in the world’s collective lexicon: the supply chain crisis.

With Father Paul’s blessing, I began a search and recovery mission throughout the basements, garages, and boiler rooms of the parish plant, searching for any solid surface upon which an icon could be painted. I found a dented and cracked four-foot board that had probably served as a school desktop. As Sherlock Holmes might have said: The game was now afoot.

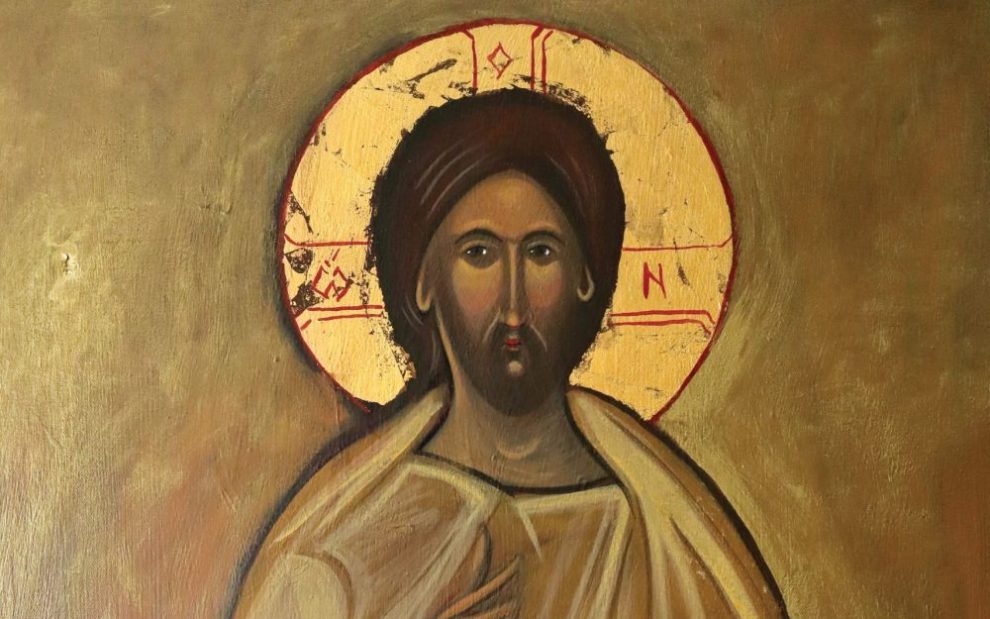

What began to emerge after several days was the icon of Christ the Healer, the silently majestic image of the glorified Lord. Instead of the usual portrayal of the torso of Christ, holding a book of the gospels and one hand raised in blessing, I chose to show just the face. The immediacy of contact with the compassionate eyes of the Creator, Savior, and Judge was both overwhelming and intimate. My icon was offered as a universal plea for help and healing.

Auxiliary Bishop Andrew Bartosic blessed the icon in a healing liturgy that was live streamed throughout the archdiocese. It was a powerful experience that spoke to a greater reality. Through our prayers, the Holy Spirit was made present in the community, now collectively reflected in the eyes of Christ the Healer.

My scavenging operations, expanded into the alleys around St. Gregory, yielded a bumper crop of more wood destined for repurposing: old paintings, damaged canvases, and framed reproductions. Another tabletop became a painting of St. John of the Cross, which I did (presumptuously) in the style of the Spanish master Diego Velázquez and the Italian genius Caravaggio.

St. John, the mystical doctor and Spanish Carmelite who composed spiritual verse of incomparable beauty regarding the soul’s journey to God, stands contemplating the rough crucifix in his hands. Like all of us wandering in the darkness of COVID-19, John is bathed in night yet fixes his gaze on the suffering Christ, whose light is reflected in the folds of his snow-white mantle.

The studio was returning to life, as was my vocation and, it seemed, the world. COVID-19 was no longer a runaway train, driverless and barreling toward the abyss. In my work on the icons, there was a slow but perceptible shift from offerings of desperation and supplication to celebrations of hope and thanksgiving. A thick chunk of desk veneer became an icon of the Theotokos Hodegetria, the God-bearer who shows the way.

The Virgin, covered in a red maphorion (outer garment) symbolizing life, passion, and suffering, holds the infant Christ child in the crook of her arm. She gestures warmly to her son, visually manifesting her words at Cana to “do whatever he tells you.” Her son, triumphant even as a child, says with his resolute gaze and blessing hand, “Do not be afraid!”

For another Pantocrator I found an abandoned canvas in an alley. The rough and damaged surface of the canvas allowed me to reduce all elements of the icon—color, form, and gesture—to simple expressions of inner reality. Perhaps the lockdown isolation was preying upon my emotional equilibrium as I fancied the icon as rendered by a time-traveling Andrei Rublev inspired by the paintings of Henri Matisse, Paul Gauguin, Paul Cézanne, and Georges Rouault at the Musée D’Orsay in Paris.

In this image Christ is seated, slightly off centered, on an unseen throne with his right hand raised in blessing and his left holding an open book that proclaims in Greek, “I AM ALPHA OMEGA.” The background is painted in a neutral earth tone covered with washes of liquid gold paint. Christ’s garments, painted in almost the same value as the background, are rendered luminous by the Naples yellow highlights radiating from his clothes, face, and hands. The canvas, like the halo and Jesus’ right hand, is wounded but, unlike the chiaroscuro of the John of the Cross image painted earlier in the pandemic, the image radiates light in four cardinal directions.

People who heard about the pandemic icons, and the few who saw them at the studio, asked the same question: What theme united them all? It occurred to me that the choice of the images and the imperfect materials upon which they were created expressed the same reality.

For years I created icons with the assumption that wood panels, expertly crafted and sanded to perfection, would always be available along with plenty of brushes, paints, and gold leaf. When that supply dried up, I was forced to grab at anything within reach, like a drowning person grasping at any object to keep from going under.

Objects I normally would have dismissed as parish detritus became life-saving flotation devices. Literal junk became symbols of hope and conduits of light when made anew as icons of Christ, the Virgin, angels, and saints. I made no attempt to repair the cracks or holes in the surfaces because, as I would tell my studio assistants when making an irremediable painting mistake: “It’s now part of the story.” Somehow, the wretched condition of the panels became part not only of my story but the story of all who, in that first year of COVID-19, would wake to a dystopian Monday not knowing if they would live to see the next Saturday.

It is not clear what, if any, lasting effect my icons could have on anyone not ultimately connected to those not simply staving off the effects of quarantine, fear, and boredom with creative activity but struggling, hoping, and praying to survive. There may have been no quantitative effect, but there were binding ties. The wounded panels linked me to the wounded world beyond my studio.

My COVID-19 icons are in themselves as brittle and breakable as the panels on which they are painted. However, when bound with the global efforts of others standing their ground and giving of self in the service of others, they become part of an unbreakable whole, a note in a monumental symphony of ministry and mission in the face of desolation.

The pastoral staff at St. Gregory continued their ministry to the locked-down, the suffering, and the poor. Scientists worked to find a vaccine. Medical professionals performed acts of selfless heroism. City, state, and federal officials around the world worked to relieve the material and financial suffering of their citizens. I painted icons.

What began as a solitary journey of fear into a heart of darkness ended as a proclamation of hope and light that rendered anew two scriptural passages I had only now began to understand. The first, from the prologue of St. John’s gospel, is, “The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness did not overcome it.” The second, from Isaiah, prefigures not only Christ’s suffering and triumph but also my fragile and broken icon panels: “By his bruises, we are healed.”

This article also appears in the September 2023 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 88, No. 9, pages 30-35). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

All Images: Copyright Joseph Malham

Add comment