On March 15, Brian Rodenas, a prison inmate in Rhode Island, wrote a note to his mom from “your favorite son.”

“I hope you’re doing good. I got in trouble so I’m in [segregated housing], get out of seg on April 18th. Don’t worry, I’m fine. I’m still coming home next year, that is my promise to you. 2024 will be my year.”

But Rodenas did not get out of “seg” in April, and he won’t keep his promise to his mother. He was returned to solitary confinement because of other minor prison infractions. On May 2 he took his own life, the third Rhode Island inmate—and the second in solitary confinement—to kill himself over a three-month period this spring.

On January 23, 300 inmates in Texas concluded a three-week hunger strike organized to protest the broad use of solitary confinement in the Texas system. Michele Deitch, director of the Prison and Jail Innovation Lab at the University of Texas at Austin, told the Texas Tribune that prisoners in Texas have been restricted to solitary for months, even years, with “their only human contact the occasional brush of a hand through their food slot while receiving a dinner tray.”

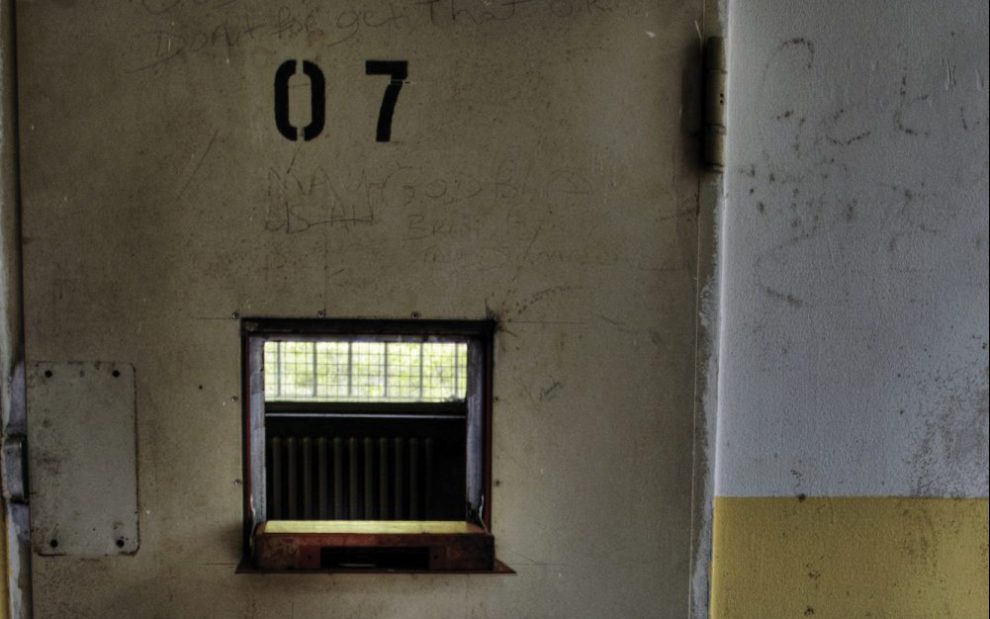

Solitary confinement as a tool of security, control, and punishment remains a “normal” aspect of life inside the nation’s criminal justice system—an expectation that is unique among industrialized peer states where rehabilitation and restoration remain primary objectives. Reliable figures are hard to come by—solitary confinement can be hidden behind euphemisms such as “involuntary protective custody”—but each day in the United States there are at least 80,000 people sealed off behind concrete and steel in units designed to diminish or eliminate sensory stimuli.

Activists who hope to end the use of solitary argue that human beings are programmed for socialization, not isolation. Under long-term solitary confinement, inmates can begin to suffer paranoia, crushing anxiety, hallucinations, and violent mood swings. People predisposed to mental illness or who are already diagnosed can be especially affected. The psychological and physical impact of prolonged solitary confinement can be long-lasting, if not permanently debilitating. It is hard to argue that such confinement does not merit the description of cruel and unusual punishment.

South Africa’s Nelson Mandela served 18 years in solitary confinement while imprisoned by the apartheid regime. He famously said that “a nation should not be judged by how it treats its highest citizens, but its lowest ones.” That standard would render a hard judgment on the United States, where the United Nations’ “Mandela Rules,” which prohibit solitary confinement beyond 15 consecutive days, have not been accepted in many jurisdictions.

But there are signs of change. Nine states are currently contemplating broad criminal justice reforms. Other states have outlawed solitary confinement for teenagers or mentally ill inmates. In several states, notorious supermax facilities have been shut down.

Pope Francis has been celebrated for his decision to declare capital punishment “inadmissible.” Less noted has been the pope’s consistent unease with lifetime sentences, which he calls “a hidden death penalty,” and the use of solitary confinement, which he describes as a kind of torture.

But if his moral appeal for the humane treatment of people behind bars isn’t sufficient, let’s recall that the vast majority of the 2 million people locked up in America’s prisons and jails will eventually return to its streets and communities. They can return to those communities whole individuals with the best possible chance of reintegrating into society or they can return damaged and broken beyond repair because of excessively cruel treatment. In a merciful, rational society, the choice would be an easy one.

This article also appears in the July 2023 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 88, No. 7, page 42). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Pexels/Donald Tong

Add comment