When Damar Hamlin collapsed on the field during the January 2 Monday Night Football game between the Buffalo Bills and Cincinnati Bengals, it felt like watching a nightmare. I could vividly imagine the fear and anxiety that must have been present for everyone who knew and cared for him. And I did the only thing I felt I could. I began to pray.

I wasn’t the only African American with this response. Across the nation, Black people sent their support and prayers to his family and friends. We saw a man suffering with no ability to physically help him, so we prayed.

At the same time, a different response began to emerge from many white allies in those same spaces. Many began to criticize the impulse to send thoughts and prayers, citing instead a need for Black people to call the NFL to account for racism and lack of care for its players. The common refrain was that thoughts and prayers will not affect change—and don’t Black folks want change?

Even though this reaction is well-intentioned, it is an example of how Black religious expression is policed in American culture. And this is nothing new in United States history, either. In the antebellum period, enslaved men and women had to sneak away to hush arbors to sing, pray, and dance without fear of their enslavers. After the Civil War, Black Christians, both Protestant and Catholic were kept from ordination, preaching, and even entering white churches. The majority of Americans opposed the civil rights movement, a revolution born from Black churches across America.

The reaction to Damar Hamlin’s injury shows how that historical racism continues to poison culture today. White allies, who are ostensibly seeking the same aims as Black men and women, criticized the same people they are trying to aid without pausing to examine why. Their response ignores important truths about African American culture and spirituality, demonstrating the gap between the desire of white allies to support people of color and the lack of cultural understanding those allies often share.

This isn’t only a secular concern. At least 75 percent of Black Catholics worship in congregations where we are in the minority. We do not regularly experience our culture and concerns reflected in the liturgies and parish programs that are offered. We rarely see people who look like us at the altar or next to us in the pews. Catholics of every ethnicity have an urgent need to expand our cultural competencies if we want to be inclusive of everyone who enters our church doors.

What cultural truths, then, are evident in the outpouring of thoughts and prayers for Damar Hamlin? First, that African religious expression across the diaspora upholds the real world efficacy of intercessory prayer. Secondly, for those of us descended from enslaved Africans, prayer has been and continues to be a response to racism when there is no other recourse.

When we speak about Black belief in the efficacy of intercessory prayer, it is critical to recognize the African influence on Black spirituality. Scholars identify many shared characteristics in religious practices across the African diaspora, whatever religion is practiced. Black Americans, particularly, show close affinity to West African religious practices—which aligns with the fact that most enslaved Africans were kidnapped from that region. Of particular importance to understand the importance of prayer are the understanding of time and community.

In the worldview passed from enslaved Africans to their descendants, past, present, and future are not separated from each other with clear linear divisions. God, too, is not detached from time. Rather, as Flora Wilson Bridges points out in her book Resurrection Song: African American Spirituality (Orbis), “God is the beginning, and God is radically related to all of existence and binds existence together in a circular relationship of connectedness and interrelatedness.” That is, all of time and history, our being, our ancestors, and our descendants are living and present spiritually through the one, true, eternal, immanent God. It is a worldview which embodies the saying of Jesus that God “is not God of the dead but of the living (Mark 12:27a).” God connects the community to God’s self and to each other throughout all of time and space.

Because of this understanding of God’s deep connection to the community, Black spirituality views God as profoundly committed to the good of the community. It also sees the ancestors as spiritually present and working as intermediaries to God for their descendants. The community, both living and dead, can intercede with God. God listens to the community because God stands at its head and wills its wholeness. Prayer, in this understanding, actively calls upon God and those in communion with God expecting something to happen. When the community prays for someone, we believe that God will act and that our prayers make a real impact on the outcome.

The belief that God will act for the good of the community is also a belief that God will act against what harms the community. For Black Americans, racism continues to be the most harmful force in our lives. The evil of racism is not logical. It harms both the oppressor and the oppressed, creating rifts in the eternal community connected through the living God. It is no wonder, then, that we continually turn to prayer as a remedy. Prayer is an action which acknowledges one’s goodness and connection to God. Prayer does not return evil for evil, but unites us to the community and to a God who works for our good. Through prayer God restores wholeness to the rifts in both the individual and the community.

It is true that not every prayer is answered in the way we wish. The mystery of relationship with God is that we don’t know what the outcome will be when we pray. Enslaved men and women cried out for years in prayer for an end to their captivity. Yet it took two centuries and a bloody war for that to come to pass. Racism has not ended and Black people still suffer disproportionately in America. Prayer, while effective, is not a magic bullet.

It is here we can only point to our Lord Jesus Christ crucified, a God who dies naked, abandoned, and alone. Sometimes what follows the prayers of Gethsemane is the Way of the Cross. This path does not negate God’s loving goodness. Instead it reveals a Savior who suffers alongside us, trusting resurrection will come. Black Spirituality sees in Christ one just like us.

These lessons from Black Spirituality are lessons for all Catholics. All Catholics believe in the efficacy of intercessory prayer through the communion of saints both on Earth and in heaven. All Catholics have moments where our pain and struggle become too much to bear and we need restoration. Everyone will have loss and grief in spite of the most fervent prayers being offered. While the wisdom comes from Black culture, it is something all people can share. So instead of criticizing the impulse to offer thoughts and prayers in times of crisis, see that impulse for what it is: an acknowledgment that God is near to us, that God cares, and that, when we pray, it does actually make a difference.

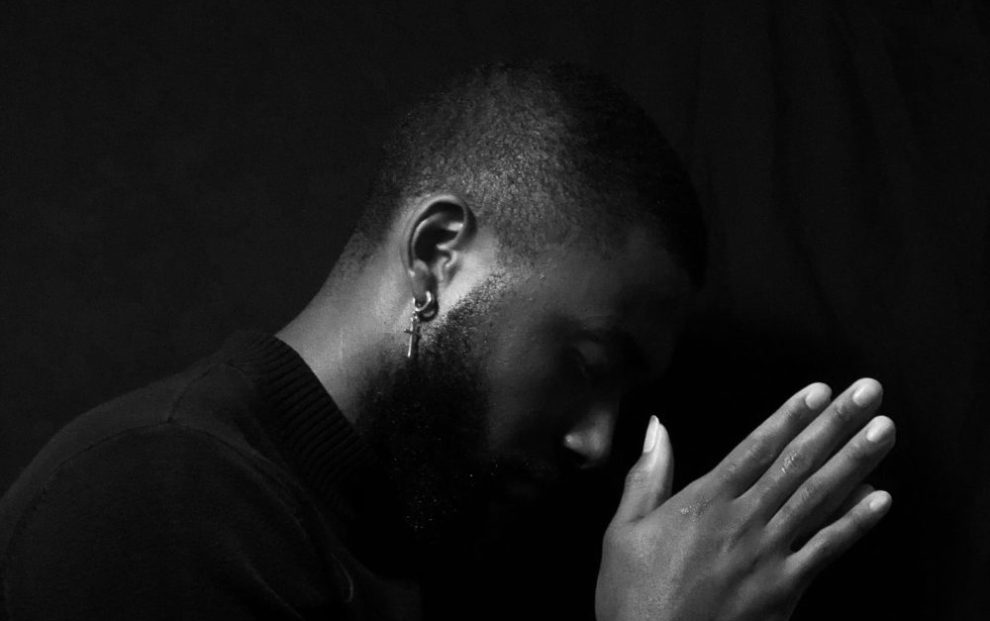

Image: Unsplash/Marquise Kamanke

Add comment