The Mary of my girlhood was modest in every way. She didn’t take up much space or make much noise. Everything about her demeanor proclaimed sexual restraint—except, of course, that she had a baby. But Mary’s motherhood did not erase her virginity. Mary was the model of discipleship offered to us as young women and, as she was a perpetual virgin, we could only hope (and fail) to imitate her.

I grew up Catholic in the 1990s on the Jersey Shore, just a few blocks from the Atlantic Ocean. We spent much of our summer jumping through crashing waves, building sandcastles, and playing “King of the Mountain” on the dunes. Bathing suits were our play clothes. Then, in seventh grade, our Sunday school teacher organized a pool party for the class. When she told the girls that two-piece bathing suits were prohibited, I was genuinely confused about why my sporty tankini—great for active play—wouldn’t be allowed. My teacher raised her eyebrows and asked, “Did Mary ever wear a two-piece?”

This was even more confusing. It crossed my mind to retort that Mary had probably never flushed a toilet either. But I began to think my teacher knew something about myself that I did not. Maybe I was veering into sin with my swim gear. I probably should have asked for further clarification, but instead I began to feel anxious about my soul. Was I unknowingly committing other actions that defiled my purity? What about my other clothing choices? Were shorts okay? Probably not. Skirts? Maybe, if they reached my ankles.

As I continued my theological education and began to adopt a feminist approach to my Catholic identity, questions about my childhood view of women’s discipleship emerged. Why had everyone focused on chastity as the most important Christian virtue? Why had my Catholic formation never stressed service to the poor or justice work as part of women’s discipleship? Was there any space within Catholic Marian devotion for me to grow into healthy womanhood? Could Mary the perpetual virgin mean anything to me as I navigated adult sexual relationships and, eventually, a sexually fulfilling marriage?

I began to wonder: What if Mary’s perpetual virginity—and, consequently, Mary as a model for women—has less to do with modesty and more to do with women’s autonomy and bodily integrity? Ironically, finding the stories of other virgins in the Christian tradition—the virgin martyrs—helped me to understand the perpetual virginity of Mary in more liberating ways.

Throughout history, men could enjoy personal and spiritual autonomy no matter their state in life. But for women, virginity was often the only path to autonomy and the primary option to resist male control. Unmarried women had more freedom to serve the poor, write, travel, or live in community with other women. They were freer to do God’s will and serve their neighbors.

As an alternative to patriarchal marriage, early Christian women fought for the opportunity to remain virgins. Women’s commitments to remain lifelong virgins were, as theologian Elizabeth Johnson puts it in Truly Our Sister: A Theology of Mary in the Communion of Saints (Continuum), an attempt to “dispose of their bodies as they pleased by keeping them out of circulation.”

Stories of women who heroically insisted upon their independence from male control, even to the point of death, have long reigned in the Catholic imagination. These virgin martyrs are models of courage and creative agency in the face of violence. Their stories show that women are not objects to be controlled but disciples of the living God who desires their freedom.

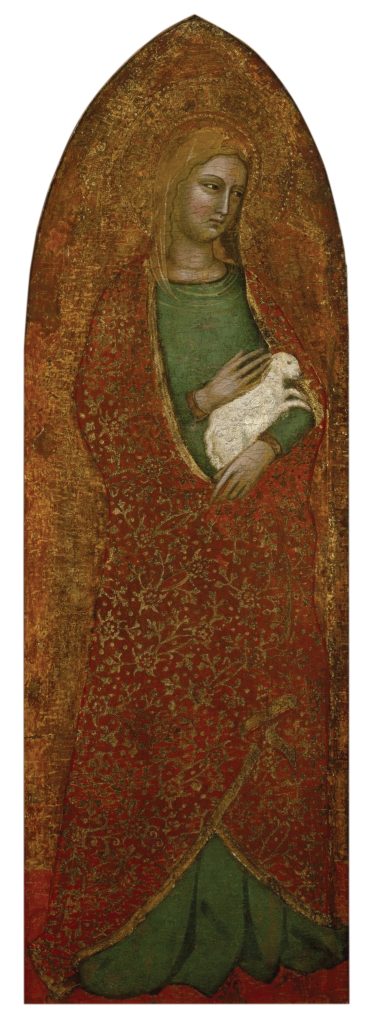

One of these women, St. Agatha, is thought to have lived in the third century. A content warning: Her story highlights resistance in the face of horrible sexual violence.

Agatha was determined to live as a virgin, but Quintianus, the consular official of Sicily, wanted to have sex with her. When she refused, Quintianus ordered his executioners to stretch her on the rack and cut off her breasts. While being tortured, Agatha declared to Quintianus that he should be ashamed of his actions and that he would never destroy her: “Impious, cruel, brutal tyrant, are you not ashamed to cut off from a woman that which your mother suckled you with? In my soul I have breasts untouched and unharmed, with which I nourish all my senses, having consecrated them to the Lord from infancy.” Agatha belonged to no man.

Later, the apostle Peter appeared to Agatha in prison and healed her. Quintianus, enraged, tortured her again. This time, the story goes, the Earth erupted in an earthquake, as if in protest of her treatment. After the inhabitants of the town demanded that Quintianus stop, he relented and sent Agatha back to jail. But Agatha, refusing to obey her tormenter, gave her soul to God and died on the spot.

Another woman of the early church revered as a virgin martyr is St. Agnes, who was pursued by a powerful prefect who wanted her to marry his son. She refused and when threatened replied: “Do whatever you like, but you will not obtain what you want from me.” The prefect then stripped her naked and sent her to a brothel. When the prefect’s son went with his friends to the brothel, hoping to assault Agnes, he was struck dead. Agnes miraculously brought him back to life, but a lieutenant, afraid of her powers, attempted to burn her at the stake. The flames parted and would not burn her, so the lieutenant murdered her with his sword. After Agnes’ death, she appeared to other women and encouraged them to live as she did.

St. Lucy, another early Christian woman who was determined to remain unmarried, took her dowry money and distributed it to the poor. The man she was betrothed to, enraged at this, denounced her as a Christian and turned her in to the local consul, Paschasius, who threatened to whip her. Lucy informed the consul that she could not be silenced because she had the Holy Spirit within her. In response Paschasius threatened to send her to a brothel to be “defiled.” But Lucy replied that nothing he did could defile her: “If you have me ravished against my will, my chastity will be doubled and the crown will be mine.” Paschasius ordered a crowd of men to attack her, but Lucy could not be moved. Paschasius then tried to burn her, but, like Agnes, she repelled the flames. Finally, like Agnes, she was murdered with a sword.

Mary, the mother of Jesus, should be understood as someone more like Agatha, Agnes, and Lucy than as someone quiet and docile. Her pregnancy disrupted her community’s notions of sexual purity. Her “yes” to God came quickly and without consultation of male authority. Her courage in traveling alone to visit Elizabeth upended the expectation that women should stay hidden at home. Mary and the virgin martyrs are models of women’s independence and singular focus on God.

Certainly, Mary also experienced the demands of marriage and family life. But understanding Mary as inspiring that early tradition of women virgins helps us remember how courageous and creative she was as she mothered God. Mary is a model for women’s discipleship not because of some unattainable purity, but because of her insistence—like that of the virgin martyrs—that she belongs to God alone.

This article also appears in the March 2023 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 88, No. 3, pages 16-18). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: St. Agatha, Guarino, Francesco, 17th or 18th century. Wikimedia Commons.

Add comment