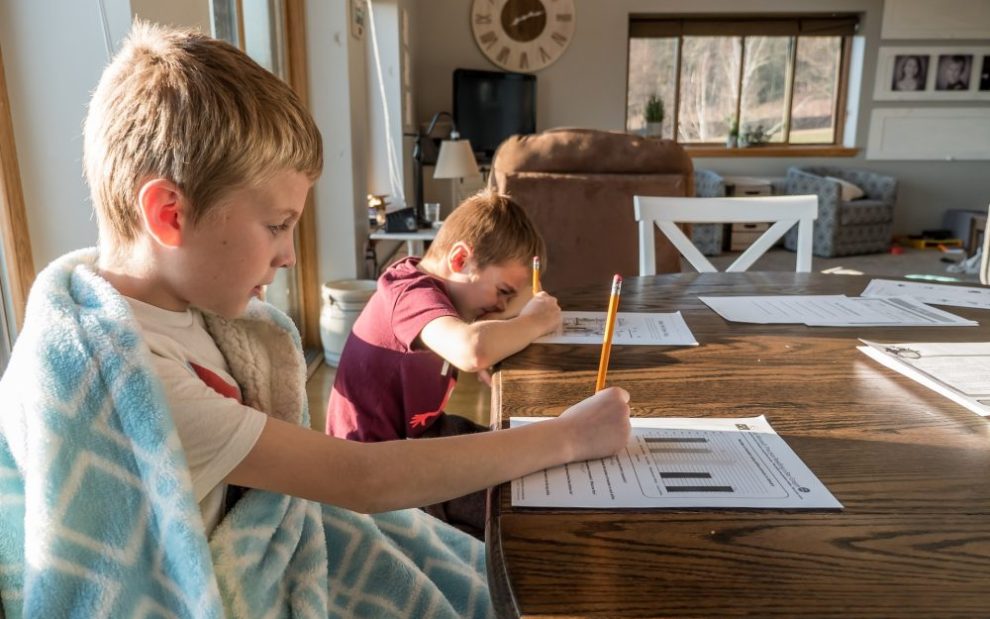

Home schooling, once a niche option for countercultural groups, has become more mainstream. Data from the Census Bureau indicate that between 1999 and 2012 the rate of home schooling rose rapidly. The rate plateaued at around 3 percent following 2012, until the COVID-19 pandemic prompted another rapid increase. In the fall of 2021, more than 11 percent of families of school-age children reported some form of home schooling.

While some home education arrangements were temporary responses to the pandemic, home schooling remains on the rise. And so do questions about its viability. The popularity of home schooling among Catholics and other Christian faith groups, especially, comes with a communal responsibility to assess its strengths and weaknesses in light of the common good.

Home schooling offers an array of benefits, including increased flexibility and greater involvement of parents in their children’s education. It can benefit students less at ease in a “normal” school environment. Parents may also opt to home-school due to concerns about public health and increased gun violence. However, there are issues with home schooling as well, especially when parents are not equipped to be educators or home-school for the wrong reasons.

Conversations about home schooling are deeply personal for me, as a veteran of the early days of contemporary home schooling. In the early 1980s, there were few home schooling programs catering to different educational needs or ideological preferences. We had no protocols for having our work evaluated by school districts. When we met other people our age and explained that we “went to school at home,” this usually translated in their minds to “didn’t go to school at all.”

My mother, a pioneer in the home schooling movement with a graduate degree in education from Columbia University, was well equipped to teach us. In retrospect, I missed out on some things, such as a more rigorous scientific education, better engagement with contemporary literature, and access to less whitewashed historical sources. Despite this, I entered college better prepared than most of my peers.

Although I missed out on team athletics and a more diverse peer group, I was lucky to live on a horse ranch that was also a retreat center and summer camp. There, I made close friends; dealt with cliques and bullying; experienced hopeless crushes; rebelled against authority; and stayed up late having impassioned conversations about God, love, life, and death. In short, I had the requisite adolescence experience.

Today, my siblings and I have graduate degrees and good jobs in fulfilling careers where we can exercise our talents meaningfully. It might be tempting to use our experience to silence critics. But the truth is that home schooling worked for us because of a variety of circumstances, not all replicable. And even when home schooling does “work” in a pragmatic sense, ethical questions remain.

First, home schooling is only possible with a certain degree of privilege. It feels strange to look back on my childhood and recognize privilege, considering how poor we were, but it is true. My parents had the privilege to choose to drop out of conventional society, the support of loved ones, and the education to know which choices were available to them. And while we were poor in money, we were rich in free time.

For home schooling to work, at least one parent needs to have time to devote to educating their children. In today’s economy, which favors the rich while burdening the working class, many families find this impossible. Additionally, some children have special needs that parents may not deal with as effectively as trained professionals. Considerations such as access to resources are also relevant.

Second, not every adult is equipped to teach their children effectively. I was lucky to have a professional educator as a parent. Other parents may not have the aptitude, inclination, or training to teach well. Teaching is a skill. It is not something just anyone can do. Our public school system exists so that every child can, in theory, have the same opportunities, instead of being held back by circumstances. We turn to professionals when we need someone to fix a car, give legal advice, or perform surgery. So why do we assume that just anyone can teach?

Third, while concerns about socialization may be exaggerated, the alacrity with which many home schooling parents brush off these questions is irresponsible. Yes, some families have access to social activities and healthy peer groups, but not all home schooling families do. And if a child’s only social interactions happen within an ideological bubble, this does not equip them to maneuver in a world where they will encounter people who live and think differently than they do.

Because successful home schooling hinges on economic, social, and geographic privileges, it is unhelpful to say “oh, just home-school” to parents experiencing difficulties with their children’s schooling. Home education may be a good option for some families, but it is not a viable alternative to fixing problems in school systems. Increased acceptability of home schooling should not mean we cease to invest in our public schools and teachers. Protecting the rights of home schooling families, within reasonable parameters, must never be at the expense of the common good.

Home schooling trends among conservative religious groups prompt additional concerns. While home schooling culture is no longer dominated by religious conservatives, it is still difficult, in some areas, to find home schooling groups that are secular or progressive. Finding an affordable curriculum that is not slanted heavily toward right-wing religious beliefs can also be difficult.

Why would this be a concern for Catholic families? Wouldn’t Catholic parents want to include religious formation in their children’s education?

The problem is that the kind of Christianity represented in these programs and textbooks is a specific iteration in which patriarchal gender roles are celebrated, science is replaced with pseudoscience, and history is slanted in favor of white European colonialism. Parents who follow the church’s teachings on social justice, and who do not view science and faith as incompatible, may have difficulty finding a curriculum that aligns with these values.

Some conservative Christian educational formats discourage dialogue and diversity. They may also create a culture of indifference to the needs of the larger community—as we saw during the COVID-19 pandemic when many conservative Christian groups were at the forefront of opposing public health measures.

Today, with the phenomenon of people “deconstructing” from harmful religious traditions, home schooling is coming under new scrutiny. Many young Christians are realizing we were fed white supremacist and misogynistic ideologies. Others are speaking out about the harm done to them in an environment in which emotional, physical, and sexual abuses may flourish, as children have fewer options for reporting or escape.

Following the mass shooting at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, the Federalist published a piece arguing that school shootings “make a somber case for home schooling.” This was not the first time conservatives responded to gun violence in this way. I have seen home schooling mothers respond to school shootings by boasting about how they don’t need to worry about gun violence, even implying that they are more invested in their children’s safety than other parents.

If an adult’s response to mass murders in public schools is indifference because it does not affect them, this makes a somber case indeed—against home schooling.

As a home schooling parent myself, I recognize that I can only make this choice because of a certain level of privilege and that this is not the only viable educational paradigm. It is simply one that works well for us right now. As other parents weigh different schooling options for their children, I encourage them not to rule out home schooling. But they should know that it comes with its own set of challenges, that it is not the best alternative for every child or family, and that it can never fill the societal need that is met by a robust and well-funded public educational system.

Image: Unsplash/Jessica Lewis

Add comment