As I paced up and down the aisles of the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels in Los Angeles on a quiet, gray January morning, I found myself transfixed by artist John Nava’s tapestries. Pausing and pointing out my favorite saints to my friend, the presence of the people of God felt palpable, even as we were basically alone in the cathedral.

In muted natural tones, Nava’s tapestries seek realism in their presentation of 136 holy men and women. The apostles are Middle Eastern. Sts. Augustine and Monica are beautifully and accurately depicted as North African. I found myself transfixed by three young women of color, Sts. Perpetua, Felicitas, and Kateri Tekakwitha, all of whom were not much older than my college students when they died. Walking interspersed among the named saints are unnamed holy men, women, and children who are simply our neighbors.

After two years of a pandemic, and as my family marks the one-year anniversary of my grandmother’s death from complications of COVID-19, pausing on the communion of saints gives me comfort. The communion of saints, with the invitation into a liminal space between past, present, and future, is something I find comforting. Yet, as I paused with the tapestries, I also felt uneasy and unsettled. I thought about the encampments of people without homes we’d walked by on our way to the cathedral.

Surrounded by all these named and unnamed holy men and women, it was not only the presence but the challenge of the people of God that was palpable. The Second Vatican Council urged that “it is the task of the entire people of God” to interpret and respond to the world around us, to alleviate suffering and dismantle injustice. Easter is a time of new possibility, a time when we renew our baptismal promises. It is also a moment for us to remember that doing so means actively living as the people of God, without fear and without exception.

For white Catholics like myself, Easter is a liturgical moment to recommit oneself to anti-racism and active work for racial justice. Division is evident everywhere we look. Antimask protests masquerading as cries for religious freedom and calls to ban books reveal a deep crisis of the common good. This crisis exists not only in secular spaces but within the church itself. In her book Towards a Politics of Communion (Bloomsbury), theologian Anna Rowlands notes that “to discern how a society views the common good requires an engagement with the mythos of a people and a willingness to be part of its (re)formation.” What might this mean for Catholics in the United States?

There is not merely one mythos of the United States, yet the narrative that many white Catholics do not want to engage but must is white supremacy. It cannot be ignored, downplayed, or treated as a relic of history. In her new book Undoing the Knots: Five Generations of American Catholic Anti-Blackness (Beacon Press), theologian Maureen O’Connell uses the image of being trapped in the “upper room of whiteness.” Like the first disciples, O’Connell argues that we are “trapped in the liminal space of a present where we assume nothing new is possible, since we’re neither learning from the past nor imagining a different future.” And as both O’Connell and Pope Francis note, being closed off in a room with only those like you makes the community sick.

We cannot build a shared sense of the common good in isolation, closed off from our neighbors, afraid of what facing deeply rooted histories might challenge us to rethink. Walking together as the people of God requires that we discern and form together a common good based on racial justice.

In Our Lady of the Angels, the people of God are presented as an inclusive and dynamic people in procession toward the altar. Each saint is depicted in their historical, racial, and cultural context. Our neighbors present similarly as we meet them walking around our neighborhoods. Nava’s tapestries invite us to reflect upon the communion of saints, but they also offer us a vision of what it means to be the people of God. And as I keep firm in my imagination that liminal space, one that is open and inclusive, I reaffirm my baptismal promises and pray that as a community the U.S. church will more fully take up the call to be the people of God.

This article also appears in the April 2022 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 87, No. 4, pages 40-41). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

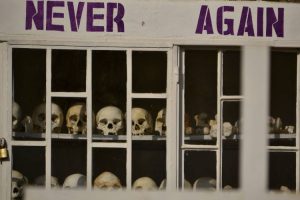

Image: Flickr/Catholic Church England and Wales

Add comment