It’s impossible to list all the books that New Testament scholar and

historian N. T. Wright has written in the space allotted on the facing

page. His career spans more than 40 years, during which he has published

dozens of books—some large, some small, some academic, and some geared

toward a popular audience—aimed at helping readers understand the New

Testament in a new light through the lens of first-century history.

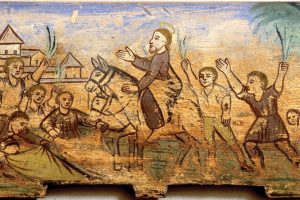

His new book, The New Testament in Its World (Zondervan Academic), is an attempt to summarize this decades-long career into a single volume accessible to churchgoers, first-year students, and scholars alike. Along with his coauthor, Michael Bird, Wright has compiled more than 900 pages of writing, illustrations, diagrams, charts, and timelines. (As Wright says, “If the 900-page book was all prose, you might think, ‘Heavens, I’m just rowing across the Atlantic. Will I ever get there?’ ”)

The resulting chapters—some of which are based on previous writing and some of which are brand new—are organized into three overarching sections: the New Testament as history, as theology, and as literature. It is vital, Wright believes, to understand scripture through each of these lenses in order to understand both its historical context and what it means to people of faith today.

Why focus on the New Testament as history, theology, and literature?

You need all three lenses to make sure that you’re understanding things correctly. In order to truly understand any text—whether it’s T. S. Eliot, William Shakespeare, or the Bible—you have to know quite a lot about its original context. Otherwise you will inevitably commit massive anachronisms.

History involves probing into the minds of people who think differently from ourselves. One of the great things about being a New Testament scholar is that we know a lot about the first century. We’ve got good source material: coins, inscriptions, the writings of Josephus, and the Dead Sea scrolls. The more we immerse ourselves in this raw material, the more we can tell what scriptural passages probably meant.

A great example is when Martin Luther challenged the typical reading of Mark 1 in the late medieval church. In the scripture Jesus says, “Repent, and believe in the good news.” Repent was translated as poenitentiam agere in Latin, which means “to do penance.” So people argued that what Jesus meant is that repentance involves saying five Hail Marys. But then Luther comes along and says, “No, Jesus means to have a change of heart.” But in fact, if you understand the first-century context you know that Luther was right, but he didn’t go far enough. People who were saying that kind of thing in the first century didn’t just mean a change of heart: They meant to have a change of politics, a change of policy, a change of agenda.

To understand the New Testament through literature is to understand the genre. When reading a parable of Jesus, such as the Prodigal Son, it makes no sense to say, “I need to know where the farm was and what the father was called.” That’s not the point of the story. And when we read Matthew, Mark, Luke, or John, they are very clear that isn’t the point of the story. Jesus is not a fictitious example of some general spiritual principle: This stuff happened, and it mattered.

That may be a trivial example, but it’s helpful to understand how books like those in the New Testament got put together and why people read them in the way they did. It’s important to know things like the function of letters in the ancient world, especially in today’s social media world where people don’t write letters anymore. I grew up writing letters. When I was in boarding school I wrote a letter home every week or I would be in trouble. But people don’t do that anymore.

And then there are books like the Revelation of John. It’s really important to know what sort of book that is, because the theology is obviously the subject matter. So much of it is about God and the world and Israel and Jesus and the church and Jesus’ death and resurrection. There’s this kind of grammar to it; it’s not just odd ideas scattered loosely around. Already in the first century early Christians were constructing what we, in hindsight, can call “theology”: There is a coherence to these ideas. It’s their attempt to read the mind of God out of the events concerning Jesus.

The church has always been at least partially defined in terms of what it believes, which means that creeds are important. No other world religion has creeds, but the church is defined as people who believe in this God rather than any others. So theology is the delighted exploration of how people address the big questions of God and the world and Israel and Jesus and us.

These three realms—history, literature, and theology—all intersect. But each also has its own proper domain. It’s possible and even desirable to examine the three lenses separately before putting them back together again.

Can you give an example of a scriptural passage that people often misunderstand?

The phrase “kingdom of God” or “kingdom of heaven” in Matthew’s gospel is often taken to mean going to heaven when you die, and it really, really doesn’t mean that. It doesn’t matter what religious tradition you’re from—Catholic or Protestant, liberal or conservative—many people make this assumption. But that’s not what that phrase is about. It’s about God becoming king on earth as in heaven: about heaven and earth coming together, not people escaping earth and going to heaven.

In the 20th century, people started assuming that Jesus’ announcement of the kingdom of God meant the end of the world. It also doesn’t mean that, although it’s interesting to track why people thought that and what effect it had on 20th-century theology. Instead, what we see in the New Testament is something more interesting and complicated: It’s the arrival of God’s kingdom on earth as in heaven, but not in the manner anyone expected. Jesus’ whole public career is saying: “No, it’s like this, not like that.” It’s not a great military revolution and certainly not like the end of the world. It’s not teaching people how to escape this world and go to heaven, but the transformation of this world and of human life within it.

How does understanding the historical context change how you interpret this passage?

Well, we could look and see what a first-century Jew might have meant by God becoming king. For example, kingdom can be considered an active noun, not a place. It’s more about the act of a king ruling and less about the place over which a king rules. If we talk about the kingdom of George I, we could draw the boundaries of his domain, but it’s more about the sort of rule he exercised, the laws he passed, what he did, and where he put pressure.

When I was working as a bishop I used to say: “What would Durham look like if God was in charge?” That’s a bit of a scary question, but that’s what Jesus is asking the whole time: “What would this world look like if God was in charge? Let me show you.” And he heals a blind man. “Let me tell you.” And he tells a parable about someone sowing seed.

He’s taking this Jewish idea that we want God to be king and saying, “OK, God will become king, but it won’t be like you think it will.”

There’s this radical misunderstanding that Jews believe in a worldly kingdom and Christians believe in a spiritual, heavenly kingdom. In other words, it’s OK to forget the world: We’re off to heaven. And although Jesus did redefine the kingdom, it wasn’t in the way Christians often think. He teaches us that the hungry for justice people, the mourners, the meek, the peacemakers, and so on are the means by which this world will become the kingdom of God on earth.

Is there one bit of historical context everyone should know before reading the New Testament?

The New Testament includes three worlds: the Jewish world, the Roman world, and the Greek world. They overlap all over the Middle East, not least in what we usually think of as the Holy Land.

Obviously, the Jews are a people with a great memory and a great narrative: “The God who called us is the God who made the world and will remake the world. Somehow we are holding on to that promise and possibility and trying to be faithful, because when he does we want to be sure we’re his people.”

That narrative clashes with the Roman narrative, which says, “The republic of Rome is now an empire, and Augustus and his successors are sons of God. They are lords of the world.” And guess what? That is being said just at the moment when early Christians are about to say, “Jesus is the son of God and the lord of the world.”

So oh my goodness, we have a confrontation here, which goes on in different modes over the next few hundred years. The Caesar cult was the fastest growing religion in Paul’s world. So when Paul says, “Jesus is Lord,” he means that Caesar isn’t. That’s serious stuff.

And then there’s the Greek context, which is fascinating. Paul grew up in Tarsus, which was one of the major philosophical centers of the ancient Near East. And he was obviously familiar with the Stoics, the Epicureans, the Platonists, and the Aristotelians and is deliberately setting out to outthink them with what is basically a Jewish philosophy rethought around Jesus.

You write in one of your first chapters that the “world of early Christianity was a bookish culture.” What do you mean by that?

The main perception of the Christian movement was that it was kind of like a philosophical club, because early Christians were talking about how the world works and they were very strong on ethics. In the ancient world, religion was not so much about ethics. The gods might care a bit about how you behave, but if you wanted to know about how to act you went to the philosophers. At the same time, early Christians were teaching one another to read. They were conducting a social experiment in which they lived as a multiethnic, outward-facing, mutually beneficial, fictive kinship group. Nobody had dreamt of doing that before.

We think of Christianity as a religion, but in the ancient world they probably didn’t: Religions had sacred buildings, priests with garlands, animal sacrifices, oracles, etc. Christians didn’t do any of that stuff. Instead, Christians had prayer and sacred texts. Of course they also had the Eucharist and baptism, but it was the words and the books that people would have been able to name as religious things.

A great many of the early converts—slaves, poor people, and women, I’m afraid—were probably functionally illiterate. Christians taught them to read so they could read Israel’s scriptures and then, later, get on board with the gospel. So one of the primary things early church teachers were doing was teaching people to read.

The early Christians were also in the forefront of the book business. Up until then most people had scrolls. If you’re a Roman gentleman in 40 B.C.E. and you have a private library, it would be a set of little pigeonhole boxes with lots of holes to put scrolls in. But the Christians wanted to have Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John all together. That was too big for a scroll, so they were among those who invented the codex, a predecessor of the modern book. A codex binds leaves together in a way that allows for more material to be put together. Early Christians were kind of responsible for this technological revolution, which I find very exciting.

Why was it so important to early Christians that people read all four gospels together?

I think there was an instinct from quite early on that the four gospels were four portraits of Jesus. It’s like when any great person gets painted: You probably want more than one portrait, because human beings are complex characters. Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John give very different facets of Jesus. And yet they’re not contradictory; they are wildly complementary. Together they provide a complex portrait of a complex yet very simple person.

The other thing is that by roughly the middle to end of the second century there were other books being written by different groups, like the Gospel of Thomas. Christians have this strong sense that they need to be telling the story in a particular way, climaxing with Jesus’ death and resurrection. Other gospels don’t do that.

How does it change our interpretation to read the gospels as a drama with a beginning, middle, and end?

The New Testament implies its position in a much longer drama. Each of the gospels evokes the scriptures of Israel. For instance, Mark starts with quotations from Malachi and Isaiah. Luke begins with a wonderful scene that could have come straight out of 1 Samuel, leading up to the birth of John the Baptist. John starts by evoking Genesis: “In the beginning was the Word.” And Matthew, of course, begins with a genealogy that runs from Abraham to Jesus, basically a summary of the whole of the Hebrew scripture.

With each of them, there’s a sense that this is the story so far, and if you read the story of Jesus without that backstory, you may put the story of Jesus into the wrong controlling narrative. The drama is that creator God calls Israel as the means of rescuing the world from its disasters. And the story of Israel is summed up densely and quintessentially in the person and work of Jesus.

That isn’t to forget Israel. The gospels say, “Jesus is the climax of the story.” All the things that the Old Testament says will come true when God sends the Messiah start coming true with Jesus.

Interestingly, that starts with care of the poor. The Book of Acts says there was no poor person among the early Christians, because they shared all their resources. That’s a direct evocation of Deuteronomy, of the Psalms, and of Isaiah. In other words: “Hey guys, scripture is coming true!”

That’s followed by a sense of, “Help, what do we do now?” A sense of going off into a strange, unmapped, new land. That’s how the narrative works: Jesus as climax sums up the long story that came before and generates a new story. It’s where the original story was always going, only people hadn’t quite seen it that way.

What do you want people to take away from your book?

I think some Christians idolize early Christians and imagine, “Oh, they had it easy. They knew Jesus, while we’re so far away.” But actually, if you look at the early church in its historical context they were just as muddled as we are, just as messed up. Even the disciples themselves, who lived with Jesus night and day, kept on getting it wrong.

I think the New Testament was partly written in order to tell the story with warts and all and to say, “Yep, that’s how it is.” Early Christians continued to follow Jesus even though they didn’t understand it all; that’s what we have to do. Obviously we struggle to understand things better, but the great news is that God doesn’t wait until we’ve understood everything before working through us.

God is not limited by our ignorance. There’s all sorts of things that none of us have quite in focus yet, but that doesn’t mean God doesn’t work in the world and through us. At the same time, if the church is to be as authentic as possible and not be blown off course, then it is urgent that every generation study the New Testament as intensely as possible to make sure that we are staying on track and not just quietly drifting away.

I sometimes say to my students, “If you’re an engineer and you get your sums wrong and you design a bridge and the railway engine is going over it and the bridge falls down, people get killed, you get sued, you may go to jail, etc. But if a theologian does the same thing, nobody will notice for about a generation and then there will be a serious decay and decline and quite possibly some disaster in a church or movement. And people may not even realize who the engineer was who got it wrong.” It’s imperative that we all work at the foundations and make sure we’re getting it right so that doesn’t happen.

This article also appears in the March 2020 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 85, No. 2, pages 28–31). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Courtesy of Zondervan

Add comment