I should take them to Utah.

Like all of my crazy ideas, this one popped into my head while I took my morning shower. As a divorced dad who lives six hours away from his kids, I’m constantly looking for new and creative ways to be in their lives.

A huge fan of the West, I wanted to see my kids’ faces when they first saw the rolling plains of Kansas, the towering Rocky Mountains, and the strange rock formations jutting out from the desert floor near Moab. Seeing their faces would be worth whatever meltdowns we might face on a 20-hour drive.

I planned the trip by contacting friends in Utah and setting up places to stay. As I talked about these plans with other people, some thought I was nuts to take a long road trip with three kids. Others thought I should stay in the Midwest and not take 10 days off of work. One person asked me, “Aren’t you afraid of being gone from work that long? Aren’t you afraid they might figure out they don’t need you? What about all the work piling up while you are gone?”

These questions seemed strange to me, as I looked forward to the break and the opportunity to spend time with my kids. I’ve always found vacations to be restorative times that help me get perspective on my life and my work. Without them, I find myself getting caught in a rut and developing an unhealthy lifestyle.

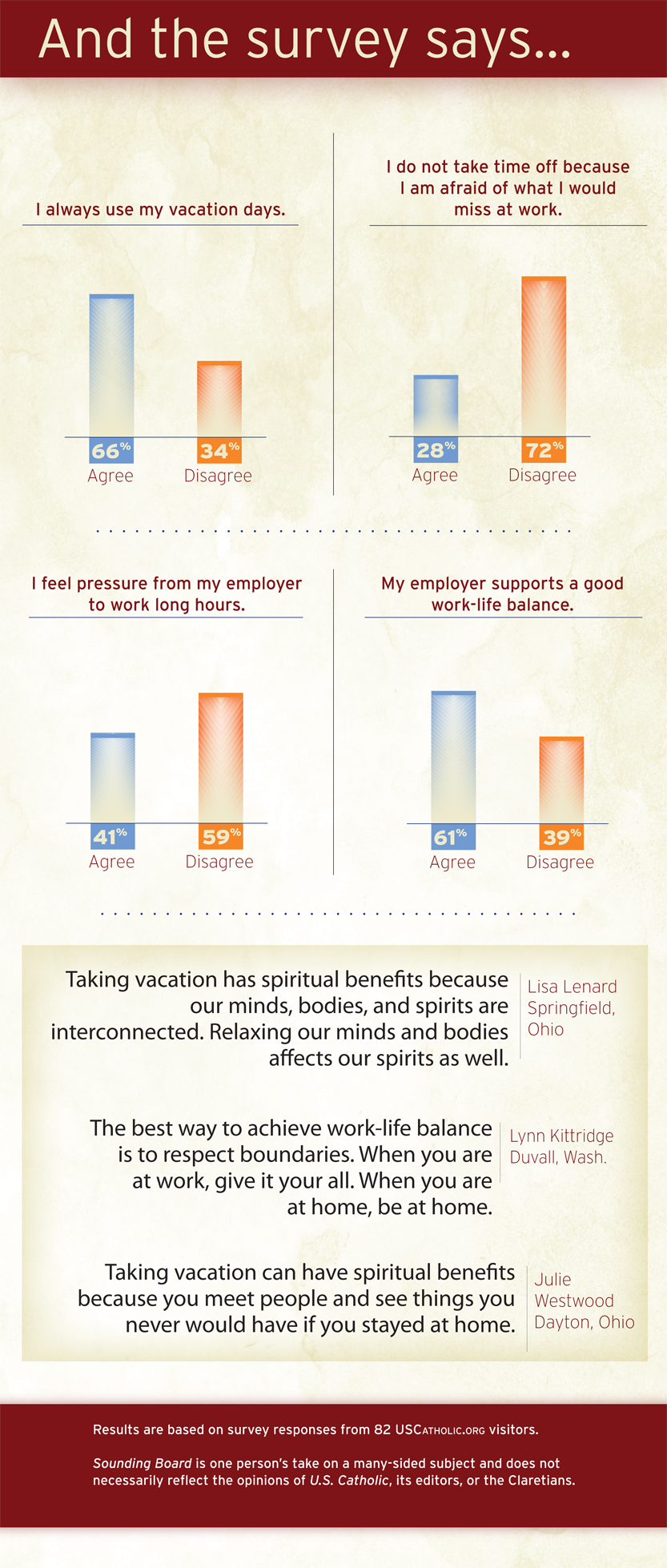

But it turns out I’m in the minority. Last July NPR ran a report about a study they did in conjunction with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. It stated that over 50 percent of Americans who work 50 or more hours a week don’t take all or most of the vacation time they’ve earned. The report contained stories about people claiming they loved work and that they were afraid to take off any time, either because something might go wrong or because someone might take their jobs.

With that amount of pressure, is it any wonder that the American Psychological Association reports that six of the top 10 most deadly diseases are a direct result of our stress levels? Why do we continue to disregard these known scientific facts and still choose not to take a break?

Alexandra Corning, a professor of psychology at the University of Notre Dame, knows why we get tunnel vision when it comes to refusing to take a vacation. “My clients often arrive in therapy due to high levels of stress. They feel overwhelmed and, although they are able to identify general sources of stress, they often are not able to arrive at effective and healthy responses to their stressors,” she says. “A vacation from our daily lives provides us the opportunity to experience a different way of living and open our eyes to new possibilities.”

People make the unwise decision not to take a vacation and get locked into a downward spiral of stress that causes more unwise decisions. St. Ignatius addresses this process when he writes in the Spiritual Exercises, “To overcome oneself, and to order one’s life, without reaching a decision through some disordered affection.” By this he means we are to center our life on Christ and everything we choose must flow from this devotion. When we don’t, we’re liable to elevate something else in God’s place and make it an idol.

Our disordered affection in America is our obsession with our work. It has become a true American idol, and we will sacrifice anything on its altar, including time with our families. But where did this obsession come from? Some historians would call it the Protestant work ethic. It’s more accurate to call it a Puritan work ethic. The Puritans believed work was the highest good and would keep the devil at bay. They claimed this position had biblical authority, but in reality it’s a picking and choosing of particular verses that suited their own worldview.

Whatever the reason, this view of work runs deep in the American psyche. It’s also in direct contrast to the Bible and the teachings of the Catholic Church, which express the value of rest and taking the time to celebrate life. This emphasis on rest is centered on Jesus’ words in Chapter 12 of the Gospel of Matthew. He explains to the Pharisees that the Sabbath was made for man, not man for the Sabbath. They had made the day of rest such a burden to their fellow Jews that it was no longer a time of rest from their labors.

Jesus reminds the Pharisees of the creation story, where God rests on the seventh day—not because God needs it but to set up the Jewish work week. There are also numerous references to rest in the law God gives to Moses, including a command for the Jubilee year, a time when all debt is forgiven, allowing a rest from the burden of financial trouble.

God builds into the Jewish mindset the idea that rest and recreation are key to a holy life. When we rest, we’re invited into a deeper contemplation of God’s love and care for us. We can’t do that when we’re constantly busy and working. God doesn’t think rest is just a good idea but commands it because it’s a vital part of our spiritual life.

In the life of a Christian, taking vacation means we can reconnect with the two chief commandments that God has given us: to love God and to love other people. With this thought in mind, I planned my road trip with my kids. I didn’t want to rush them from one site to another. Instead I wanted them to take the time to rest and breathe, to reconnect with these commandments. I hoped it would remind them of their own dreams for their lives.

At breakfast on the first day of the trip, we talked about taking a pilgrimage to worship God and appreciate God’s gifts. In Kansas we stopped at the Cathedral of the Plains and the wood-carved beauty of the Cathedral of the Madeleine in Salt Lake City. In each place we lit candles and offered up prayers. On Palm Sunday we went to Mass at a small parish in Moab and kept our palms on the dashboard of the car for the rest of the trip.

We reconnected as a family, driving for miles, singing absurd songs, and listening to ghost stories on podcasts. I watched as my youngest drew pictures and wrote about our experiences in her trip notebook. I smiled as my middle son shared his encyclopedic knowledge of the various places we visited, expanding the research he learned before we even got in the car. And I stood in awe as my eldest son climbed up small notches in a canyon wall.

None of this would have happened if I hadn’t risked challenging the idol of work in my own life. I could have skipped vacation, edited another book, and been considered valuable at work. But I’m glad I didn’t. I doubt I’ll remember most days at work when I’m 80. But I’ll remember that trip because it helped me step outside of my own perspective to see God and the developing personalities of my children. With my reordered affection toward God and my kids, work resumes its proper place in my life. All because I took my vacation days.

This article also appears in the July 2017 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 82, No. 7, pages 25–28).

Add comment