Putting aside, for a moment, the election of a reality TV star as president of the United States, history may ultimately judge that the most significant cultural event of 2016 was actually the awarding of the Nobel Prize for Literature to Bob Dylan. That decision, handed down by those ultimate high-culture deciders in Stockholm, finally ratified the ascension of the American popular arts that began in the music and movies of the 1930s, built to a crescendo in the 1960s, and has been the new normal for most people ever since.

Scholars have been nominating Dylan for a Nobel for years, but nobody really expected him to get the award. After all, he is, or at least was, a pop star, so his elevation was bound to raise questions. The most common one went like this: “Sure Dylan’s work, most of it anyhow, is great, but is it literature?” The Nobel committee hedged by citing Dylan’s “new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition.”

In purely literary terms, Dylan’s work represents the evolution of a multiracial American folk tradition that had already entered the canon through the likes of Carl Sandburg and Langston Hughes. After an apprenticeship at the feet of Woody Guthrie, in the mid-1960s Dylan arrived at a fusion of that tradition with a surrealist and symbolist stream of poetry that came down to him through Allen Ginsberg and the other Beats. In Dylan’s subsequent work, the folk tradition became a natural, living expression of what it feels like to be human in the postmodern world. Literature, from Homer onward, is, among other things, the expression of a people and their times, rooted in their history and traditions. And that is precisely what Bob Dylan has been doing for the past 55 years.

The centrality of the folk tradition in Dylan’s work has been indelibly confirmed over the past 20 years. After his career floundered for a while in the 1980s, in 1992 and ’93 Dylan regrouped and put out two albums of traditional folk songs, performed solo with guitar and harmonica. Then, in 1997 at the age of 56, he came out with his first album of new material in seven years. Time Out of Mind was a startling return to form that won the 1998 Album of the Year Grammy and launched an astonishing renaissance that has continued through the late 2012 release of Tempest.

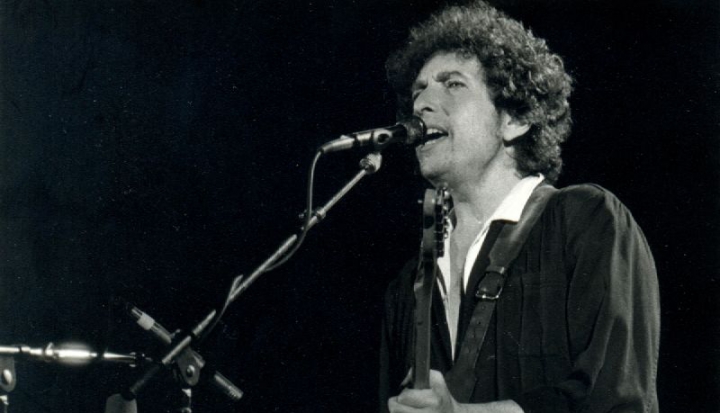

After the initial spate of headlines, outrage, and elation over the announcement of Dylan’s Nobel, the artist himself kept the story alive by refusing to acknowledge the award. In Stockholm, the prize committee sat by a silent phone as night after night Dylan went on stage, played his shows, and never uttered a word about the prize.

Those mind games about the Nobel are, of course, right in line with Dylan’s lifelong pattern of cultivating an air of mystery. Ever since he changed his name from Robert Zimmerman, the creation of a character named “Bob Dylan” has been a central aspect of his art. He arrived in New York claiming to be an orphan who had been bumming around the country since he was 12, when in fact he’d had a very conventional middle class Jewish boyhood in Hibbing, Minnesota. This was the same guy who, for a while there in the mid-1970s, performed every show in white face. This shape-shifting aspect of the Dylan legend was best captured by Todd Haynes’ brilliant and baffling 2007 movie, I’m Not There, which claimed to be “inspired by the music and many lives of Bob Dylan.” In that film six radically different actors portray different Dylan personae with different names. And all of them sing the songs of Hibbing’s own Robert Zimmerman.

One of the roles Dylan tried on for a few years was that of a born-again Christian (though Dylan argued such a label wasn’t accurate), a move heralded by the 1979 release of the album Slow Train Coming. But the excitement this generated among evangelical Christians quickly faded into bafflement as Dylan also explored his Jewish roots and later seemed to move away from any formal religious practice. But those Christians who had celebrated Dylan’s conversion missed the point. By 1979 Dylan had already been spouting mystic prophecies for most of two decades. For example, “A Hard Rain’s A’Gonna Fall,” with its “seven sad forests” and “a dozen dead oceans” has ancestry in the books of Revelation or Daniel. And “When the Ship Comes In,” which Joan Baez sang at the 1963 March on Washington, paints a vision of justice delivered (“the chains of the sea will have busted in the night”) that echoes the prophet Isaiah.

During his great comeback of 1997 Dylan, in a rare moment of candor, settled the question of his religious leanings by reaffirming his allegiance to American roots music traditions. “I believe in a God of time and space,” Dylan said, “but if people ask me about that, my impulse is to point them back toward those songs. I believe in Hank Williams singing ‘I Saw the Light.’ I’ve seen the light, too.”

With the Nobel recognition of Dylan, a historic corner has been turned. There is now room in the cathedral of literature for every charismatic and uncredentialed genius who has seen a light and can find a way to make us see it, too. Having recognized a neo-poet of the pop culture era, the Nobel literature committee should also start looking at our neo-novelists, the filmmakers. When they are ready to consider an American again, they really should look at Martin Scorsese.

This article also appears in the February 2017 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 82, No. 2, pages 38–39).

Image: Flickr cc via Xavier Badosa

Add comment