When Time magazine and the New York Public Library compiled their lists of great children’s books, authors notorious for their Christian motifs—like J. R. R. Tolkien, C. S. Lewis, and the late, great Madeleine L’Engle—were well represented.

The representation of Christian writers on the list doesn’t come as a surprise to historians of children’s literature. Spiritual formation has long been an important theme within children’s books.

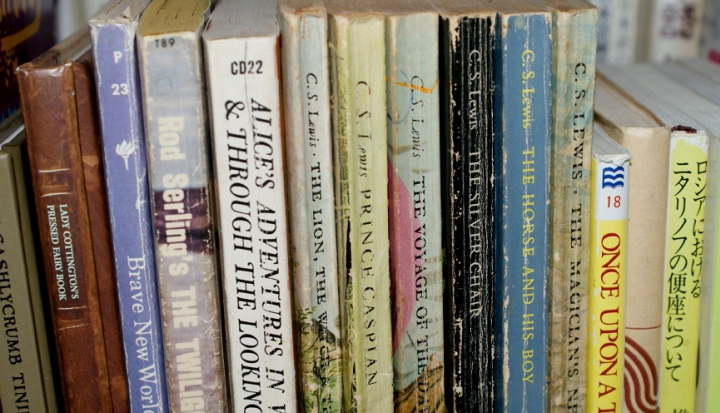

The first literature written specifically for children was, in fact, a basic primer for living a good, faithful life. The Venerable Bede, Aelfric, St. Aldhelm, and St. Anselm all wrote school texts in Latin during the Middle Ages, which continued to be used in schools in England and colonial America for hundreds of years. In his twin masterpieces for children, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking Glass (1872), Lewis Carroll (the pen name of Charles Dodgson) uses Wonderland—a place no human but the eponymous Alice has seen or experienced—to encourage children to place their trust in matters of spirit and faith that cannot easily be defined.

God’s unconditional love and forgiveness for humanity, from pre-flood Noah to the military arms race of our present era, is one of the prevalent themes of Madeleine L’Engle’s Time Quintet (1962–1989), as is the importance of adding beauty to the world through artistic and scientific exploration.

In my 10 years in children’s book publishing, one of the questions I have been asked time and time again at industry conferences is, “Why are there no Christian writers writing for children and teens today?” The truth is that there is a plethora of children’s books with Christian motifs in the industry today; the cultural touchstones of children’s literature have just changed in tone to meet the realities of modern children and childhood.

Most people outside of the children’s book industry are unaware of the large number of children’s books published each year. What you see on the shelves of Barnes & Noble, at your local indie bookstore, or featured on Amazon or in a Scholastic book fair are really only a fraction of the titles produced by children’s publishers around the world. Children’s book publishers used to release only a few new titles a month; now larger publishing houses like HarperCollins can publish as many as five new titles per imprint per week.

While some might assume that this heightened production is a result of the publishing world’s constant search for the next Hunger Games or Divergent blockbuster—and it would be valid to do so—it’s also true that children today have such varied interests and cultural experiences that figuring out what stories captivate them or they find relatable can be unpredictable.

Yet, if you look at the descriptions of any of these new releases, you’ll notice that thematically they all come down to one thing: how to live a good, meaningful life. In this way, children’s literature continues to explore the same themes of spirituality and faith that its authors have explored for hundreds of years. For example, while Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy (1954–1955) could be summed up as a multi-arc and multi-perspective narrative of the Fellowship’s journey to face and embrace their own natures while battling the great evil of Sauron, Emery Lord’s When We Collided (Bloomsbury) narrates a teen’s struggle to leave an artistic mark on the world and not self-harm in the wake of her diagnosis with bipolar disorder.

Literary giant David Levithan’s entire canon of work between 2003 and the present day reinforces for readers the importance of love in various forms—self-love, romantic love, friendship, the bonds of family—and forgiveness, just as C. S. Lewis’ Chronicles of Narnia series did almost 60 years ago.

In Levithan’s Every Day (Random House), protagonist “A” wakes up each day in a different body, living someone else’s life. It’s a lonely existence . . . until A meets and falls in love with Rhiannon. As A endeavors each day to interact with Rhiannon—in different bodies of all shapes, genders, sizes, and socioeconomic backgrounds—Levithan raises important questions regarding whether we fall in love with someone’s external trappings or their soul. Similarly, the Pevensie siblings only find the ability to unify and successfully liberate Narnia from the White Witch in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe when they are able to see and love each other for who they each intrinsically are, rather than the people they want each other to be.

Both When We Collided and Every Day present a key tenet of Christian teaching—respect for oneself and others. They remind readers to look beyond topics that might be considered controversial to what makes us each beautiful in God’s eyes. Both books also reflect the reality of young adulthood today and uphold the notion of human dignity.

As such, it would be wrong to assume that children’s books no longer promote a Christian perspective or that there are no longer Christian authors writing for the mainstream audience today. The Holy Spirit is always present and at work, even in books you might not expect. If you put off reading Phyllis Reynolds Naylor’s Alice series (Simon & Schuster) because she puts her characters in realistic situations teens encounter growing up, including masturbation and casual sex, you’ll miss a wonderful testament to the importance of using our gifts to change the world. If you neglect to read Neil Gaiman’s Newbery Medal and Carnegie Medal winner The Graveyard Book (HarperCollins Children’s Books) because the protagonist lives with several ghosts in a graveyard, you’ll skip a fantastic commentary on not being afraid to define your own identity and belief system, even in the face of tremendous pressure to act a certain way.

Books for children have changed so much over the years and the evolution of them will, no doubt, continue as society’s values evolve. After all, many of the books on Time magazine’s and the New York Public Library’s lists, including ones from Tolkien, L’Engle, and Lewis with overt thematic and doctrinal ties to Christianity, have been burned and banned for their “immoral” content at some point in history.

But as long as children’s literature continues to promote and encourage works with universal messages of love, forgiveness, and courage, I have no doubt there will be plenty of new Christian children’s books and writers for children to discover.

This article also appears in the August 2016 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 81, No. 8, pages 32–33).

Image: Flickr cc via vintagecat

Add comment