“Know who you really are and how God can use you,” one of my seminary teachers exhorted. Living this injunction, simple albeit powerful in message, has been an unfolding journey over my three decades of pastoral ministry and my current calling as a minister in the United Church of Christ.

I have always tried to understand who I really am, as well as the person I ideally want to be. However, not only is my ideal self unreachable, it is also inauthentic. As my seminary teacher pointed out, God wants my real self, which means that even characteristics that I deem blemishes can be used for God’s purposes. It is for this reason that I connect with St. Columba of Iona, who ancient biographies reveal as a complex character who was both “wolf” and “dove,” and who—similar to me—actively worked to embrace the contrasting aspects of his authentic self.

In 521 Eithne, the wife of Fedelmid Mac Fergus of Donegal, bore a son named Crimthann, which means “wolf.” They hoped he would possess the wolf-like cunning desired by their clan. But Crimthann’s spiritual disposition earned him another name, Columba, which means “dove.”

Columba’s parents sent him to be educated at the monastic school of Moville, where he showed strong inclinations toward spiritual contemplation, leading to his ordination as a deacon. Historians fail to record Columba’s calling to the priesthood, but later folk tradition tells of a vision in which an angel instructs Columba, “Arise and renew sound doctrine in Ireland.”

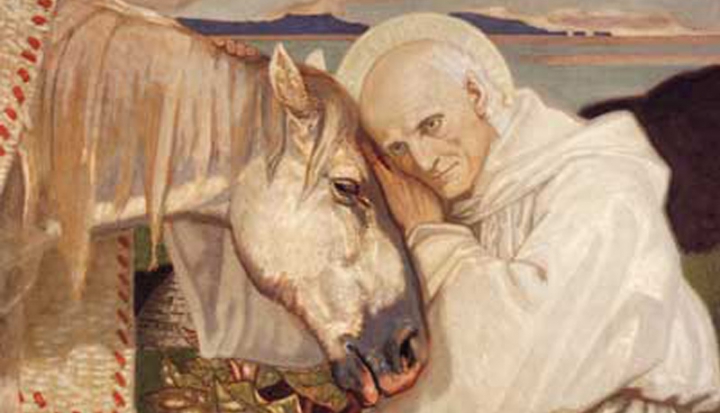

Columba’s dove-like attributes were certainly part of his real nature. He was famous for gentleness toward animals; he once received a vision that a wounded heron would land on the shore—and when, sure enough, it arrived, Columba cared for it tenderly and released it back into the wild. Like the saint, I’ve benefited from the companionship of four-footed and winged friends, from a raccoon on a log in the forest with his hands folded that seemed to be praying beside me to my beloved dogs.

Columba could be equally as tender with emotionally wounded people; in one recorded incident, an estranged husband and wife saw their love for one another passionately restored after Columba prayed with them. In discharge of my own calling, displays of dovish compassion have been vital. I’ve helped dig a grave, counseled people in a late-night crisis, and followed an ambulance to the hospital.

Yet, throughout his life, Columba’s cunning inner wolf often shadowed his dovish qualities. He worked tirelessly for the kingdom of God—but also for his own political faction. When Columba established a monastic empire, he appointed his Uí Néill clansmen to rule each abbey and then asserted the right of his abbots to crown local rulers.

Columba’s wolfish ways were also evident when he coveted and stole another monastery’s special Book of Psalms. The High King of Ireland ordered Columba to return the book, but Columba called his clansmen to arms, resulting in a terrible battle and slaughter.

Following this barbaric feud, the leaders of Ireland’s churches banished Columba from the Emerald Isle. This banishment cast him onto the shores of Iona, in Scotland’s Hebrides, where he built the monastery that established Christianity in Scotland. Today, Columba’s Iona Abbey draws thousands of pilgrims from around the world.

This incident calls to mind how I’ve had to learn to deal with my own pride. One of my spiritual mentors told me, “No one follows a perfectly pure calling, there are always bits of pride or ambition mixed in. The trick is to recognize them.” My parents were scientists, and my father had multiple postdoctoral degrees, so I learned early in my life to idolize education. This led to an intellectual arrogance in seminary and into my pastoral career. Early in our courtship, I practically drove my wife-to-be crazy by arguing over obscure points of doctrine. Seeing the shortcomings of such hubris has been a valuable lesson in tempering my wolfish self.

It would be easy to say we all have our good and bad sides, but Columba’s dove and wolf natures defy categorization as good-versus-evil. God used both the dove and the wolf within Columba. Without his wolf’s strength, Columba would not have evangelized Scotland, unafraid of jealous opposition from Druids and Pictish chieftains. He needed cunning and a warrior’s courage to proclaim the new faith and establish its churches across the land. According to legend, even the Loch Ness Monster heeded Columba’s stern command. Yet, along with the saint’s wolfish side, his dove-like compassion was also essential for God’s purpose. As Columba healed broken relationships, cared for the sick, and addressed the needs of common people, he applied salve to the wounded nature of the stratified, violence-ridden Pictish society.

As I look back at my decades in ministry, I can see the value of having a complex and sometimes contrasting personality. Often I’ve acted as a dove, but hard circumstances have sometimes required a wolf’s cunning and resolve. All aspects of my nature—even those that might be thought contradictory to one another and those I dislike—have proven at times to be necessary.

As a child, I feared my father’s anger. He was mostly a wonderful parent, but he had a passive-aggressive streak. He would quietly go along with the rest of the family until he could bottle his feelings no more, and then he’d occasionally lash out in sudden fury. In one such outburst, when I was 11 years old, he bent my BB gun into a metal pretzel because my Beatles music annoyed him.

I learned to fear displays of strength or defiance—in my father and in myself.

But my calling to ministry has required me to allow the wolf to come out on occasion—not to let the wolf behave in savage fury, but to growl when necessary. In several of my churches, I have had to deal firmly with issues of congregational safety. I conduct thorough background checks on every person involved in church ministries. When potential legal issues are flagged, I set boundaries and give notice that any violation will result in a report to appropriate legal authorities. Responses vary, from “Thank you, Pastor” to “I’m not coming to this church again.” Sometimes, the sheep in a congregation benefit from their minister keeping a wolf’s eye over the flock.

After Columba’s death, his monks on Iona wrote down his instructions for their way of life. He said there were “three labors in the day, which are prayers, physical work, and reading.” Columba didn’t quantify the amount of daily reading, but he did recommend, “Your measure of prayer shall be until your tears come” and “Your measure of physical work shall be until you have much perspiration.” Pray until you cry and work until you sweat; the saint’s advice reflects his own approach to life, experiencing all the raw emotions that came to him without flinching, struggling with the world in its earthiest forms. This full welcoming of reality enabled him to embrace both the wolf and dove aspects of his nature. In my life and ministry, Columba of Iona walks beside me, unrelenting in his call to embrace tears, sweat, and the complex fullness of who I am.

This article also appears in the August 2016 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 81, No. 8, pages 45–46).

Image: Via Wikimedia Commons

Add comment