In 2013 Pope Francis banished a bishop who scandalized the church in Germany by building a lavish $34 million residence. The German media dubbed him the “luxury bishop.” From the very beginning of his papacy, when he paid his own hotel bill and chose a small car, Francis has walked the Christian walk and impressed many by doing so.

He has said in an address to seminarians and novices that it “truly grieves me to see a priest or a nun with the latest model of a car,” asking them to pick a more “humble” one. He concluded: “And if you like the beautiful one, only think of all the children who are dying of hunger. That’s all! Joy is not born from, does not come from things we possess!” The pope is serious about clergy and religious being witnesses to simple living.

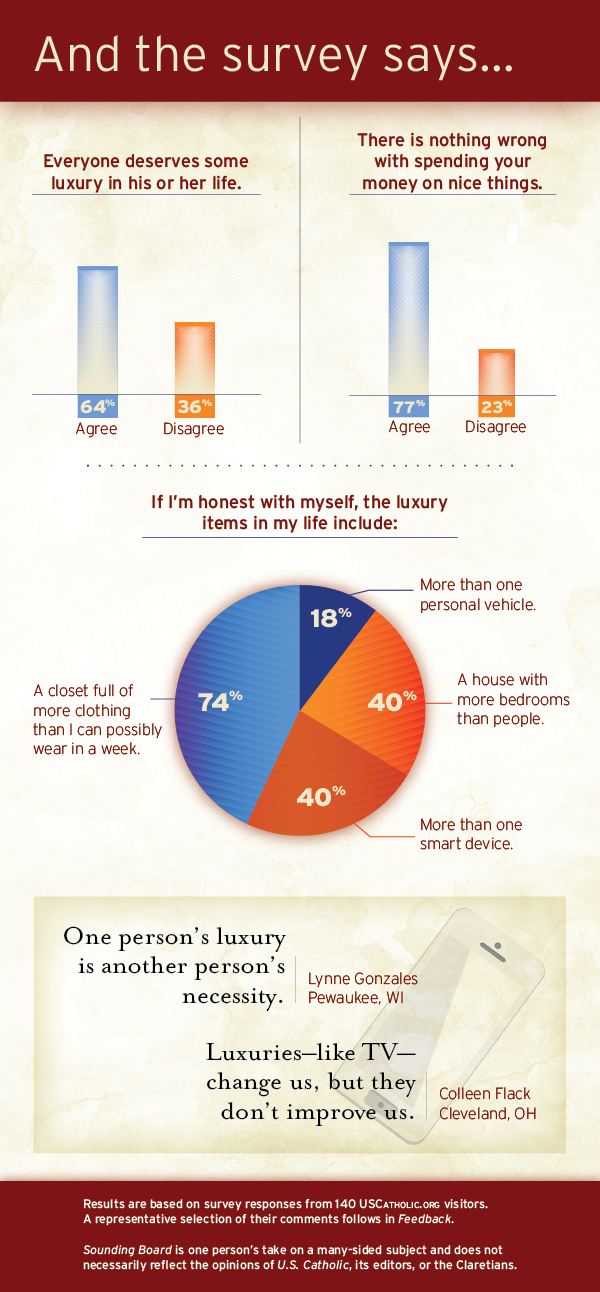

But it’s always easier to pick on the sins of others. What about the sin of luxury in our own lives? Hasn’t “too much” become an ordinary, acceptable standard in our own homes and parking lots? The philosophers of the ancient world and the prophets of the Israelites were united in criticizing such displays of excess wealth and, from Plato on, the term luxury was applied to this vice. They weren’t against all possessions; they just thought there was a line, an “acquisitive ceiling” (in historian Brad Gregory’s words), beyond which humans shouldn’t go. Luxury meant an inordinate desire for possessions and—as the story of the luxury bishop illustrates—we continue to share a sense that things can go overboard. But don’t we go overboard all the time in our daily lives?

It is true that Jesus’ disturbing commands to leave all possessions behind have never been applied to all Christians. We do not all have to be St. Francis. But, on the other hand, we shouldn’t ignore these commands. Glen Stassen and David Gushee suggest Christians try to avoid the problem of luxury by spiritualizing it to death; we tell ourselves we can have possessions as long as we are “detached” from them. Yet, if we are really detached, then we should be able to discern and reject excess as luxury.

But where do we draw the line? In his speech, Pope Francis joked that someone might respond to him by saying, “So, Father, you are telling us to use a bike?” No, he said, cars are useful for getting certain things done, but one does not need “fancy” for that. The pope’s example points us to how we define luxury. To discern it in our own lives, we need to ask the question: What are possessions for?

The word sin is derived from a Greek word for “missing the mark.” You can only know sin if you know the target at which you’re aiming. Our possessions, according to the Catechism (no. 2402), have two purposes or targets: to meet the basic needs of our household and to “allow for a natural solidarity” to be built among people. We go overboard—and miss the mark—when we use possessions to create and serve false needs in ourselves and to foster rivalries among people. That’s the vice of luxury: We want lots of things we don’t really need, and getting those things incites envy and competition with others. It’s a vice because we become habituated to it; it’s as if we are accustomed to pursuing fancier stuff even when it’s clearly unnecessary and the old stuff works fine.

In the back of our minds, I think we know the truth of these statements. We know keeping up with the Joneses is silly, and we know that stuff won’t ultimately lead to our happiness. Indeed, a lot of studies by social scientists back up our intuitions. Excess stuff and materialistic competition with others don’t make for higher levels of happiness. Yet we seem unable to stop as a society, constantly escalating everything material. And besides, isn’t that new iPhone just so cool?!

It is cool—magical, even. But here’s where we face a particular problem in today’s world regarding luxury that the ancient thinkers never imagined. We have a whole industry of marketing dedicated to telling us over and over how “magical” this or that consumer item is. Why? Because we will spend more money if we’re convinced of the magic. One instructional book for makers of high-end products reminds them that what they are selling is not simply a material thing, but a “feeling,” a “desire to feel special.” Another suggests luxury products correspond to a “dream” and a “quest.” Yet another praises a certain tech company seen by its millions of devotees as not “just a brand” but a “religion.”

From a Catholic perspective, we should recognize the potential magic in material things. We even have a word for it: sacrament. But it’s a very different kind of magic. Beyond the seven sacraments, many Catholic thinkers talk about a “sacramental worldview” in which we are constantly building up the spiritual relationship with God and neighbor through the material world. The most common example? The gift. Gifts—before they became objects of marketing frenzy—were seen as an example of sharing material goods in service of the invisible bonds of social solidarity.

Pope Benedict put this “astonishing experience of gift” at the center of his writings on the Catholic economy. He said we should strive to make all our economic interactions with others have a quota of gift within them. This possibility of gift, of a sharing of excess to build up human relationships, is the real magic latent in our possessions. The marketers of luxury simply want to redirect it; they know material goods aren’t just material goods. They try to convince us that the magic is about an experience for yourself or an exclusivity that sets you in a special club above others (who don’t or can’t have the luxury).

Thus, we really have a choice. If we are fortunate enough to have excess possessions, will we hit or miss the target? Will we pursue the illusory magic of luxury or will we make our excess a sacrament for God and for others?

It’s not wrong to have possessions or even excess possessions. As I said, not everyone receives the call, seen often in the gospel, to leave everything for Jesus. But that doesn’t mean everyone else is off the hook, especially those of us living in the richest country in the history of the world. Instead, we too have a choice.

It’s a choice many of us face every day. Bishop Robert Barron writes that when you are faced with any purchase, ask yourself: Can I do with less? Or can I do without? Like starting an exercise program, this can be painful at first, but after a while, it’s liberating, especially since it frees up other possibilities for the resources. This is probably the most important point. Instead of luxury, we can use our resources to build bonds of solidarity and love through our purchasing.

For example, buy something handcrafted with real love and skill. Or buy from the farmer who actually cares well for his animals and his land. You pay a bit more, but that’s exactly the quota of gift Benedict talks about. You don’t pay more for some phony magic. You pay more in order to make the purchase a sacramental exchange, an effective sign of God’s grace active in the world and in your life. That’s hitting the target. And if Catholics do this regularly and together, the world will respond to our parishes much the same way it has responded to Pope Francis: by recognizing we are people who actually walk the walk.

This article appears in the March 2016 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 81, No. 3, pages 32–35)

Add comment