There’s a certain diagnosis you will hear over and over if you start to ask Catholics about Jesus—particularly about other Catholics’ relationships with Jesus. “I think for some people, Jesus is a Facebook friend who you sometimes want to block from your newsfeed,” says Jake Braithwaite, who attends a Jesuit parish in Manhattan. “I have friends who I imagine have yet to find a way that makes sense to them and meets them where they are. At this point, maybe he’s an acquaintance rather than a close friend.”

Braithwaite and his friends aren’t alone. “Catholics often have an easier time talking about the church than they do about Jesus,” says Jesuit Father James Martin, author of several popular books including his most recent, Jesus: A Pilgrimage (HarperOne). “Catholics can talk ’til the cows come home about Pope Francis, their own parish, and Mass. But when you ask them about their relationship with Jesus, they’re tongue-tied.”

Historically—and stereotypically—Catholics have not been as comfortable as some Protestants using the language of “friendship” with Jesus. Even referring to a “relationship” with Jesus can sound too intimate and casual. But that seems to have been changing in recent decades, as the Catholic Church has formally encouraged laypeople to open their Bibles and encounter Jesus directly. So, after decades of cultural and theological changes piled on top of centuries of tradition, what is the state of the American Catholic relationship with Jesus in 2015? How do Catholics talk about Jesus, conceive of him, and connect with him?

“When people say, ‘What would Jesus do?’ I say, which one?” Martin says with a laugh. Jesus has always been a figure whom some will try to mold to the perceived needs of the time—and then reinterpret when times change. When artist Warner Sallman painted his iconic portrait of a blue-eyed Jesus in 1941, for example, he was inspired by a dean at his Bible college who had encouraged him to paint a Jesus who was “virile” and “rugged, not effeminate.” Within just a few decades, that ubiquitous painting was derided by other Christians for possessing exactly the opposite properties. One critic called it a “pretty picture of a woman with a curling beard who has just come from the beauty parlor.” Even when it comes to one particular image of Jesus, people see what they want to see.

Some of the difficulty has to do with the shifting winds of culture. But it also stems from the remarkable range of depictions of Jesus in the gospels themselves. Mark emphasizes Jesus’ humanity, calling him a carpenter and referring frequently to his emotional responses. In the book of John, by contrast, Jesus is first a divine figure who is then made flesh. Taken as a whole, the gospels present Jesus as a remarkably complicated figure, at times serenely above the fray, at other times impatient, even angry.

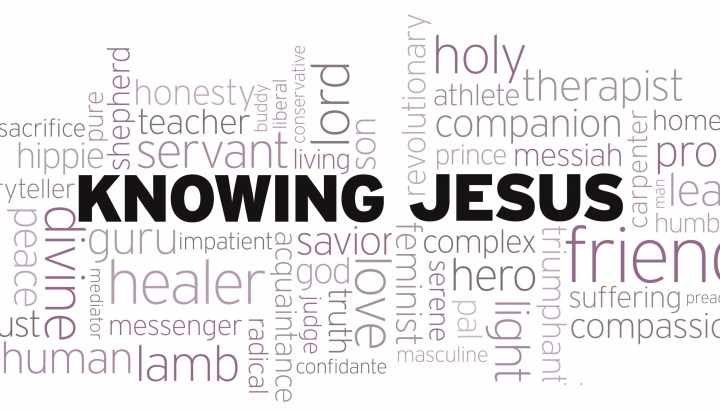

If anything, the intervening millennia have only made a “true” picture of Jesus more difficult to capture. If you go looking for Jesus in Christian culture today, you’ll find just about any character you want to: therapist Jesus, hippie Jesus, revolutionary Jesus, feminist Jesus, masculine Jesus, and guru Jesus, not to mention still-popular traditional images of Jesus as the healer, the shepherd, and the teacher. There’s blond Jesus and black Jesus, suffering Jesus and triumphant Jesus, and even athlete Jesus and homeless Jesus. There’s the Jesus glowing with purity and holiness, and the one defined by his roughness and humanity.

Father Robert Barron, a well-known author, speaker, theologian, and founder of the media ministry Word on Fire, has even advanced the notion of Jesus as a “divine fighter,” a nonviolent warrior. In short, today it’s less clear than ever what a person might mean when he or she refers simply to “Jesus.”

Past and present

For some scholars, the answer to Martin’s question—Which Jesus?—ought to be a simple one. The only knowable Jesus is the man whose life can be verified through scholarly historical research, nothing more or less. In the 1980s and ’90s, this approach culminated in the founding of the Jesus Seminar, a group of scholars who attempted, with much fanfare, to reconstruct a coherent and verifiable account of the life of Jesus on earth.

But many Christian scholars, including many Catholics, object to this rather limited view. Luke Timothy Johnson, a New Testament scholar at Emory University in Atlanta, has been critical of the historical Jesus movement on the grounds that it ignores what makes the figure of Jesus so meaningful to so many Christians. “It seems to me it’s not only futile and impossible to accomplish, but beside the point,” he says. The parts of the gospels that most trouble historians—Jesus’ miracles and other historically implausible occurrences—are the parts that tend to resonate most with believers. “For Christians,” Johnson says, “Jesus is a present living reality, and the resurrection is not just something that happened on Easter . . . it’s an invitation to the life and power of God.”

“You have to understand both the Jesus of history and the Christ of faith,” says Martin. “They’re the same person.” Since Jesus was a first-century Galilean, it’s impossible to understand him without some knowledge of first-century Galilee. But Martin emphasizes that the divine Christ is just as important as the historical one. In Jesus: A Pilgrimage, Martin traces the path of Jesus’ life through Bethlehem to Galilee to Golgotha and beyond, in search of the Jesus both fully human and fully divine.

Passionist Father Donald Senior, professor emeritus of New Testament studies at Catholic Theological Union in Chicago, argues that it’s possible to appreciate the specificity of Jesus’ identity as a first-century Jewish man while still maintaining faith in a divine and eternal figure. In the decades since Senior first published his book Jesus: A Gospel Portrait (since revised, Paulist), he says he has come to appreciate even more deeply the historical reliability of the gospels. “They’re not histories in our sense of it, obviously, but there’s a credible connection between the circumstances of first-century Palestinian Judaism and what was going on in that world, and what is still embedded in the gospels,” Senior says. “I find, more and more, the depth of those links.”

Partly in response to the restrictive approach favored by some proponents of the historical Jesus movement, Johnson has put forward the idea of the “living Jesus,” one who is “not merely a memory that we can analyze and manipulate, but an agent who can confront and instruct us,” as he put it in his 1998 book Living Jesus: Learning the Heart of the Gospel (HarperOne). As Johnson reflected recently, “Jesus is not a figure of the past like Socrates or Plato or Caesar; he is present in the spirit—not physically, but in the spirit.”

Jesus is my BFF

For laypeople, scholarly wrangling over Jesus’ exact movements and words in the first century may not be of pressing daily concern. Instead, the question is more often closer to Johnson’s formulation: Who is Jesus today, or perhaps more important, who is he to me?

In the Evangelical Protestant tradition, it’s commonplace to hear Christians talk about Jesus as their “best friend” or “personal savior.” Catholicism, by contrast, has typically emphasized mystery and holiness. For some, then, it’s more natural to dwell on Jesus as God more than man. “Catholics in general are more comfortable with the divine Jesus than they are with the human Jesus,” Martin says, “maybe because so many stories we hear on Sunday are the miracle stories.”

But it’s clear that the last half century has brought significant changes to the way laypeople read the gospels along with an increasing comfort and familiarity with the person of Jesus. Johnson makes a distinction between expressions of piety before and after the Second Vatican Council. Before the council, piety regarding Jesus focused overwhelmingly on his divinity; although it was vibrant in its way, it was very different from what Johnson describes as the “Jesus is my Lord and savior” expressions of Protestantism. Johnson sees a shift when the council encouraged laypeople to read their own Bibles in English, which he said fostered a “more robust appreciation for the ministry of Jesus, not just the mysteries of the incarnation.”

The fifth-century scholar St. Jerome said that “ignorance of the scriptures is ignorance of Christ,” a line now embedded in the Catechism of the Catholic Church. But it was only with Vatican II that Catholics were actively encouraged to read their Bibles independently, something many now say is the most meaningful path to encountering Jesus. Dei Verbum, the council’s 1965 document on divine revelation, also proclaimed that “easy access to sacred scripture should be provided for all the Christian faithful,” including accurate translations in multiple languages.

Over the ensuing decades, those clear and radical instructions led to a flowering of Bible studies, video resources, and other popular study tools that have given laypeople much more familiarity with the Jesus of the gospels. In more recent years, a renewed interest in lectio divina, a Benedictine practice of reading and prayer, has led more people to direct encounters with scripture.

But Martin says the lack of those types of encounters persists even today. “Some Catholics misunderstand the Jesus of the gospels because they’re not as familiar with the gospels,” he says. “They’re familiar mainly with the passages read out loud on Sunday. So because there’s not a history of Bible study as much [in the Catholic Church], they miss out.”

Today that long-standing tension means there can be some discomfort even with the language of having a “relationship” with Jesus, or with thinking of Jesus as a living presence as opposed to a remote deity. Senior questions whether most Catholics see Jesus as a living person who is part of their lives. “For a lot of Catholics it’s not quite that clear,” he says. “I think for some, Jesus is an example. He’s understood to be divine, to be God incarnate. But it’s not like some other person—not that unctuous, immediate emotional contact that I think evangelical piety has.”

But the changes over the last half century have contributed to a landscape in which many Catholics do indeed talk about having a personal relationship with Jesus. Jake Braithwaite, the New York Catholic who sees his peers struggling to develop a relationship with Jesus, grew up attending Catholic schools near Philadelphia. His parents were deeply involved in a parish on the campus of Villanova University. Braithwaite, now 26, says his social and spiritual life revolves around the Church of St. Ignatius Loyola, a Jesuit parish on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. Those experiences have deeply influenced how he sees Jesus.

“There’s something that has been stressed formally and informally throughout my education about God becoming flesh, and how radical that incarnation is,” Braithwaite says. “He celebrated meals with friends, and went to friends who were sick. I can share my relationship with Jesus just as much in those times as in a more conventionally religious [moment].”

For Braithwaite, Jesus is a teacher, a friend, and a storyteller. “I turn to Jesus a lot to understand how he saw and lived in the world when he was a part of it,” he says. “I go to his life as an example, and as a teacher, really frequently in things both large and small.” Whether it’s a petty office dispute or a significant family issue, contemplating Jesus’ approach is a way for Braithwaite to reorient his own thinking. “My human instinct is so often to do things one way, and then when I look at Jesus, the way he radically went against a lot of those instincts—not that those instincts are wrong, but there’s a higher level we aspire to from his example.”

Braithwaite says he maintains a connection to God through the Eucharist and through prayer, which he compares to a conversation. More unusually, he also finds a kind of spiritual experience in the theater, where “you’re in the same room as the people telling that story.” But he feels a communion with Jesus in particular in “those really person-to-person moments, because I know Jesus felt all those things, too, in this very human way.”

Ivalyn “Tee” Jones-Actie is 53 and serves as a eucharistic minister at her large, primarily African American parish in Baltimore. She describes her approach to Jesus as a “personal relationship, a friendship.”

“It’s very intimate, where I can talk to him and go to him with anything, and I know he’ll never fail me,” she says, adding with a laugh: “I may not always get what I think I want, but I’ve come to know that what I wanted was not always what I needed.” Raised Baptist, Jones-Actie converted to Catholicism because her first husband, whom she married in 1981, was Catholic. When he died by suicide five years into their relationship, the church served as a comfort and support for her and her two young daughters. She eventually met her second husband there.

Today, Jones-Actie says the Eucharist is one of the most meaningful ways she maintains her relationship with Jesus. But she also finds him in prayer, in her parish’s Bible study, by listening to Christian radio, and in talking with him. “I don’t consider it prayer, but I talk to him a lot,” she says. For her the physical image of Jesus as a “gentle African American man” is the one that resonates most. “If he says we’re made in his image, that gives everyone the right to see him in their image,” she says.

Relationship boundaries

Some might fear that opening the door to the quasi-evangelical language of Jesus as a “friend” runs the risk of molding Jesus in the image of each individual believer. As Senior puts it, “This idea of ‘Jesus my buddy,’ it doesn’t fly with the gospels,” which Senior sees as portraying a Jesus who is always somewhat elusive and mysterious. “The more intimate your language, the more personal, the more sentimental—there’s a certain influence of our culture on that way of piety.”

In some extreme cases, a devotion to Jesus becomes something so unique it is separate from a devotion to the church. Novelist Anne Rice, who has published two novels about the early years of Jesus’ life in addition to her well-known series of vampire novels, made headlines in 1998 when she returned to Catholicism. More than a decade later, however, she announced she was through with the church—but not with Jesus. “I remain committed to Christ, as always, but not to being ‘Christian’ or to being part of Christianity,” she wrote on Facebook. “It’s simply impossible for me to ‘belong’ to this quarrelsome, hostile, disputatious, and deservedly infamous group.”

But in Martin’s experience, if the relationship with Jesus is grounded in the gospels, it’s more likely that the opposite will happen: Jesus molds the believer, not the other way around. “More often people encounter the Jesus who can be challenging, not the Jesus who is tamed and nonthreatening,” Martin says. “In the story of the rich young man, Jesus says to give up everything. That means different things for different people, but it’s challenging.”

In some ways the Catholic Church, with its many centuries of argument, tradition, and cohesion, is uniquely situated to absorb and mold the more evangelical-tinged expressions of personal encounters with Jesus. “The church is first of all a historical institution with traditions, a creed, a canon of scripture, and a teaching authority,” Johnson says. “This provides a framework for those experiences.”

The church is also profoundly centered in community, Johnson adds. Encountering a living Jesus within the church’s practices ensures that “it’s not so much ‘Here’s what Jesus said to me this morning’ but ‘Here’s what we as a community are discerning as the work of the Holy Spirit and Jesus’ presence among us.’ ”

According to Senior, the experience of Jesus is in a way mediated for Catholics. “For a lot of lay Catholics, those that participate in a regular way in the Eucharist, there is the presence of Christ there, but it’s more a communal experience,” he says. It’s that thoroughly communal aspect of Catholic culture that Senior sees as protection against the excesses of the radically individualistic mind-set.

“The liability for the evangelical experience,” he says, “is that it becomes sentimental and it becomes individualized: ‘This is my Jesus.’ ” By contrast, the emphasis on community helps push back against those instincts. “If we’re in tune with the full spectrum of authentic Catholic tradition, I think it’ll help us from having a truncated view of who Jesus is.”

Which Jesus?

With the multiple Jesuses offered up by American culture, it can be hard to know how a layperson can go about finding the right one. Some versions have perhaps been overemphasized, while others go sadly ignored for long periods.

“I think that one of the elements of the Jesus of the gospels we have tended to lose sight of is prophetic Jesus,” Johnson says. That Jesus is most visible in Matthew and Luke, which both depict Jesus as countercultural, one who challenges his followers to see the world in a truly different way. “I think sometimes Catholics are too eager to settle in with the Gospel of John, with its picture—true in its way—of Jesus as bringer of divine benefits.”

As for theologically troubling interpretations of Jesus, like the wealthy Jesus offered by proponents of the so-called “prosperity gospel,” there’s at least one solution that might help correct them. “The way in which these are countered is living within the framework of the living community, with its traditions, its canons, its creeds, and its sacraments,” Johnson says. “An effective way of demolishing those reified Jesuses is by reading through the gospels slowly from beginning to end. The Jesus we encounter in the gospels is infinitely more demanding, more living, and more resistant to our projections than we might imagine.”

Suzanne Harris, a lifelong Catholic who attends a parish in Spokane, Washington, describes Jesus as a friend, though she does not always distinguish between her relationships with Jesus and God the Father. “He’s someone I can talk to, to share my ideas with, my joys, my concerns,” she says. “Like any friend, I don’t necessarily always agree or want to listen to what he has to say, but it’s just so completely part of my life. I don’t think more than an hour or two goes by in a day where I don’t think, ‘Oh, that was wonderful!’ or ‘What were you doing there?’ Most of my prayer is just regular conversation.”

Along with that daily flow of conversational prayer, Harris says she encounters Jesus through other people, particularly those at the margins of society. It calls to mind Jesus’ words in Matthew 25, that to help those who are struggling or forgotten is to help Christ himself. So when Harris sees a person in need, she says, it is a reminder that “Jesus is right here with us, all the time.”

Harris concedes that her sense of the ever presence of Jesus may still be unusual in the church. “I think many people grew up with an idea of God as someone distant, who holds power over us and we have to please him. Or they have this child’s picture of Jesus, the baby Jesus in the manger,” she says. “Unfortunately, too many people don’t have a close, personal relationship with Jesus.”

For some, their approach to Jesus changes as their life changes direction. “In my experience as a priest, when people are suffering greatly or in some kind of crisis, their relationship with Jesus becomes much more personal and emotional,” says Senior. “The crucifix, there’s an idea there, even for people for whom this has not been their usual practice; in a moment of suffering they’ll turn to that and find consolation in that.”

Meanwhile, individual traditions within the church will suggest their own paths and styles. Martin, a Jesuit, suggests that Jesuit culture and traditions lend particular insight into Jesus—after all, the order’s full name is the Society of Jesus. The most common Jesuit method of prayer is imaginative contemplation, in which the person praying imagines being within a scene from the gospels. “Nothing is as important to me as that kind of prayer,” Martin says. “You experience yourself in the scene and can appropriate it for yourself. It becomes not simply someone else’s experience of the resurrection, but your experience of the resurrection.

“Ignatius says that after the meditation we should have a conversation with Jesus as one friend to another,” he adds. “It’s something more and more Catholics are becoming comfortable with.”

This feature appeared in the April 2015 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 80, No. 4, page 12–17).

Add comment