Just when I thought I’d outgrown mentors, a friend introduced me to David Stang. His enthusiasm for his favorite subject, his sister Dorothy, is contagious.

“She whacked me around as a kid,” he admits. “A tomboy, she played the best football in the family.” That tenacity carried Dorothy Stang through the Amazon, where she was a feisty defender of the poor and the rain forest. After her death, Stang continues to be a role model in the arenas of the environment, aging, and women’s roles in the church.

Her story has the attributes of heroic legend, so let’s tell it that way. First, the setting. In Brazil less than 3 percent of the population owns two thirds of arable land. When the government gives land to displaced farmworkers, loggers and ranchers burn their poor settlements, sell the valuable timber, and graze cattle (to supply our McDonald’s!). The resulting loss of the rain forest is tragic: It contains 30 percent of the world’s biodiversity. Some call it “the lungs of the planet,” and as it shrinks, global warming increases.

It’s hard to imagine a place more distant from Brazil than Dayton, Ohio. Young Dorothy lives here, her backyard a model of organic gardening where she learns composting and the dangers of pesticides. In 1948 she joins the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur and becomes a teacher. Rather than becoming a benevolent nun who dies of old age in a quiet convent, this is where her story gets interesting.

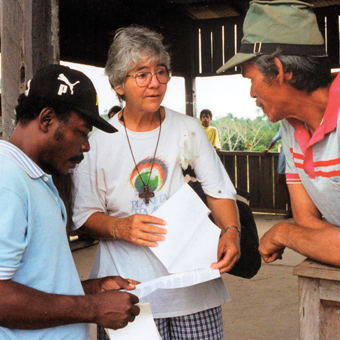

Our heroine volunteers for Brazil when her order calls for missionaries. She accompanies families to Pará, a state bordering the rain forest, to defend their land. Stang organizes people into cooperatives: They learn crop rotation, read the Bible, and worship with music and dance. Because priests are scarce, she becomes their shepherd.

When her people are attacked, she tells them brusquely, “Quit crying; start rebuilding!” Her old VW Beetle wobbles over bridges with rotting planks—where David makes a nervous sign of the cross. Stang takes the peoples’ case to the government. When officials deny receiving her letters, she finds them in their files. Persistenty she asks for protection of poor farmers, but nothing is done.

Amazingly, she keeps this up for 38 years. Stang starts fruit orchards with women and projects for sustainable development with 1,200 people. The Brazilian Bar Association names her “Humanitarian of the Year” in 2004.

Enter the villains. The ranchers hire gunmen who shoot her to death on Feb. 12, 2005. Seeing the gun, Stang doesn’t run or plead for her life, as most folks would. Instead she pulls out her Bible and reads the Beatitudes aloud. She must’ve spent a lifetime preparing for that moment. Now she teaches me how to live.

When I breathe in the piney air at home in the Rocky Mountains, I recall Stang’s joy outdoors. Without much institutional church, she finds God in the cathedral of forest. Stang reminds me that when we lose our sacred connection to the earth, we’re stuck with small selves. In film footage she proudly shows off a tree farm, exulting, “We can reforest the Amazon!”

Stang has encouraged me to stop eating beef, since grazing requires destruction of the rain forest. I’m learning “green” alternatives to wasteful habits. Like most North Americans, I have enough stuff and now lean toward a simpler life. David explains, “She was so in love with what she was doing, she didn’t notice her dirt floor, primitive plumbing, no electricity.”

Holy once meant pious and passive. But Stang models how to raise Cain and act for justice. As we baby boomers age, Stang is patron saint for slow butterflies and reluctant caterpillars. She didn’t remain captive to her upbringing. Vivaciously she tried new things, journeyed to new places. Her face is so youthful, it’s hard to think of her as 73. If I want to look that luminous at that age, I, too, must shed fears and risk.

I want to love as gladly and fully as she did. It’s easy to get caught up in trivia: social commitments, work deadlines, domestic chores. But is this how we want to spend the precious coinage of brief lives? At Stang’s funeral her friend Sister Jo Anne announced, “We’re not going to bury Dorothy; we’re going to plant her. Dorothy vive!” If I want that immortality, I should examine what seeds I’m planting now, how I’ll live on in memory.

Stang has ruined my easy cop-out: How can one small person offset complex and apparently hopeless wrongs? Stang and I are the same height, 5 feet 2 inches. Yet look what this giant accomplished: Her killers’ trials, televised to every Brazilian classroom, have given children hope.

Her family and community won’t pursue canonization, preferring to give the poor that money. Many already consider Stang a saint and martyr—in the early church that’s all that mattered. As for her role as a woman, David has the final word: “Don’t ever call my sister second-class!”

This article appeared on the April 2008 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 73, No. 4, pages 47-48).

Add comment