A priest prone, his face to the floor, his arms stretched like broken wings. The chapel silent and expectant. Thorny-voiced Isaiah: “He was despised and forsaken; he was pierced for our transgressions; he was crushed for our iniquities.” Then the voices from all around the chapel—the young priest near the altar, a girl high in the balcony, a boy in a deep dark corner:

“What is truth?” says Pilate.

“Hail, King of the Jews.”

“And they struck him repeatedly.”

“We have no king but Caesar!”

“Behold your mother.”

“And bowing his head, he gave up his spirit.”

Silence.

The congregation sinks to its knees as if stricken all at once.

“We swim in an ocean of tragedy,” says the priest quietly, “and around us there is death and despair, Columbine and Oklahoma City, war and disease and death. But light defeats darkness. Christ defeats death. Death has no dominion over us. We are not a Good Friday people but an Easter people.”

And we pray, for the Jews, who were first to hear the Word, and for the pope and bishops and priests, and for unbelievers, and for the sick, and for travelers, and for us all, every one, and then the young priest walks over to the massive wooden cross and hoists it aloft over his head, straining with its oaken weight, and then he hands it to the altar boy and the altar girl, and they prop it up between them, and the most extraordinary hour of the Catholic year begins for me: the Veneration of the Cross.

The ritual is ancient, having originated in Jerusalem shortly after the supposed recovery of the cross of Jesus in the fourth century. From the Holy City it spread across the early Christian world with the spread of relics of the cross. By the year 750 it had found its way into the liturgy of Good Friday in Rome, and from the Eternal City it spread to every corner of the Catholic world, even unto this small cedar chapel at the edge of the New World at the edge of the 21st century.

The slow, poignant shuffle begins. I sit in the balcony and weep, overcome by the prayer and poetry of these faces from every walk of life, men and women and children of every shape and size and state of disrepair, a microcosm of the entire church itself walking slowly toward the symbol of a gaunt man’s murder many years ago—to kiss it, touch it, remember him by it.

An old man who cannot bend. His wife who bends.

Twin girls, teenagers.

A priest with cancer. A teacher whose father died Tuesday.

A girl in overalls. A girl with loud shoes. A boy all long bones.

A man, seven feet tall, who folds down to touch the crosspiece. A woman with an infant in arms. The infant stares fascinated.

A woman with a walker whose walker hits the cross as she turns away.

A girl, sobbing.

Some bend in to kiss the cross as tenderly as you would kiss a child.

A girl who leans her head against the cross for an instant. A priest, barefoot. A small boy who kneels some feet away, awed.

Some touch it with one finger, two fingers, one hand. One man embraces it.

A blind man whose steps shorten carefully as he senses the cross before him. A girl with her leg in a cast.

A girl with a hole in her jeans. A man who carefully removes his glasses and closes his eyes before he kisses the cross.

A woman helping her aged mother. A man with a cane.

A girl who leaves a lover’s kiss.

A weeping man.

A very large man who stays long on his knees.

The choir, one by one.

The musicians-oboe last.

A gaping girl, led by her mother.

The young priest, the altar girl, the altar boy.

The end.

This article appeared in the April 2001 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 66, No. 4, page 49).

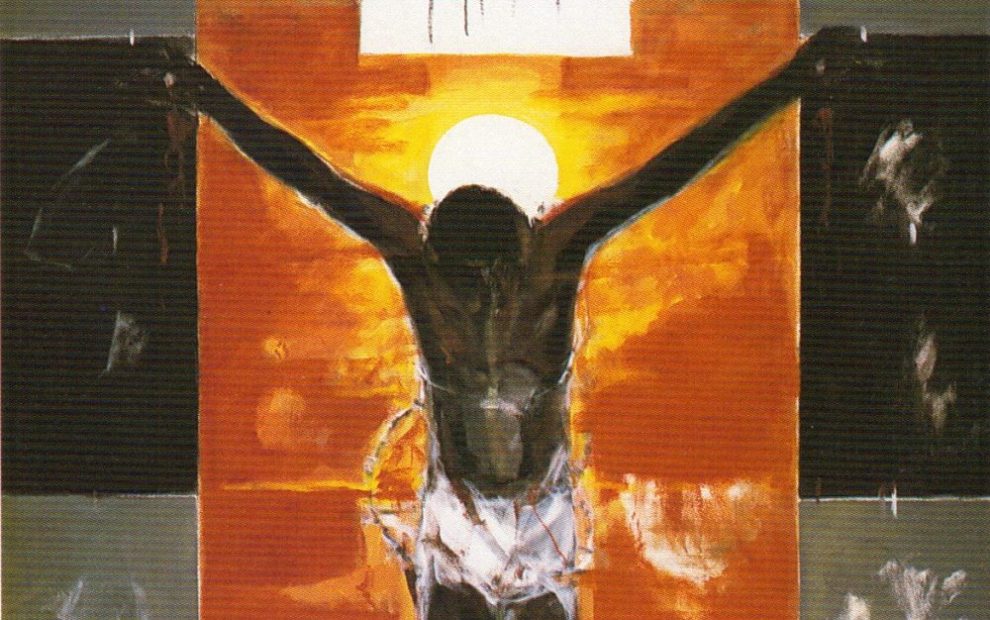

Image: Wikimedia Commons/RuizAnglada, Cristo Negro, 1995 [CC BY-SA 3.0]

Add comment