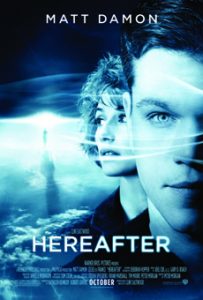

Hereafter

Directed by Clint Eastwood (Warner Brothers, 2010)

For almost half a century Clint Eastwood has been making films about death, but nearly all of these movies have been violent adventures in which death arrives as an apocalyptic horseman of vengeance, punishment, or damnation. Now, at long last, the octogenarian filmmaker is taking a curious, unblinking look at death as loss and wondering—in a way his earlier films rarely did—what it is like for those left behind in its wake.

For almost half a century Clint Eastwood has been making films about death, but nearly all of these movies have been violent adventures in which death arrives as an apocalyptic horseman of vengeance, punishment, or damnation. Now, at long last, the octogenarian filmmaker is taking a curious, unblinking look at death as loss and wondering—in a way his earlier films rarely did—what it is like for those left behind in its wake.

Over the past two decades Eastwood has become America’s most serious mainstream filmmaker, probing and dissecting the Hollywood myths of redemptive violence that earned him box office success. Unforgiven and Mystic River explore the folly of vengeance with stories that transform Eastwood’s earlier avenging angels into tragic figures worse than the men they kill. Flags of Our Fathers and Letters from Iwo Jima deconstruct patriotic fables sanctifying our violence and demonizing our enemies, and Invictus and Gran Torino explore the virtue and redemptive power of forgiveness and reconciliation.

At the heart of Eastwood’s turn from redemptive violence is a curiosity about those left behind by death and suffering, and a growing suspicion that additional violence merely postpones and multiplies this tragedy. In Hereafter Eastwood trains his lens on the fundamental terror of our mortality, without wrapping it in a violent narrative distracting us with enemies and heroes. Here Eastwood’s heroes are painfully ordinary people wrestling with the frightening mystery and insult of our mortality, humans wanting to look away and focus on the routine of daily life.

In this Eastwood tale there is no escape into violence or into a utopian future where death has no sting, only a willingness to sit with characters facing the terror of our mortality with a poignant consciousness that death is a part of life. In this sense the main character (played by Matt Damon) seems to have it right. You don’t have to be afraid of being alone.

This article appeared in the January 2011 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 76, No. 1, pages 42-43).

Add comment