When Jesuit Father Brian Strassburger celebrates Mass at migrant shelters on the U.S.-Mexico border, he pops open the trunk of his minivan and takes out a folding table, a mobile speaker, and his photography bag turned Mass kit. He then invites people to use whatever seats they have as pews. These liturgies are not unlike those of the early church. But as Strassburger, the director of Del Camino Jesuit Border Ministries, says, they differ from what “you would get in a very pristine Catholic church.”

Many people have discussed the significance of the Eucharist in the church’s life over the past five years. In 2019, a Pew Research survey reported that only one-third of U.S. Catholics believe in the real presence of Jesus in the Eucharist. Six months after the survey, the COVID-19 pandemic hit, and Mass attendance dropped significantly in the following years.

While later surveys have questioned whether the wording of the 2019 Pew survey produced accurate results, these factors motivated the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops to institute a three-year National Eucharistic Revival. This included the 2024 Eucharistic Congress, which brought together about 60,000 people in the Lucas Oil Stadium in Indianapolis. The Congress’ roughly $14 million price tag and its emphasis on eucharistic adoration brought some criticism, but some attendees found the speakers and the worship experience to be powerful.

The history of the Eucharist: from meal to mystery

When today’s Catholic leaders seek to “revive” the Eucharist in the U.S. church, what precisely are they bringing back to life? After all, this sacramental ritual has changed significantly since Christianity’s first few centuries.

The history of the Eucharist indicates that this was originally part of a larger late afternoon or evening meal, with roots in both Greco-Roman and Jewish traditions. Exactly what this meal looked like varied from region to region. “There is tremendous diversity in the early church,” says John F. Baldovin, a professor of historical and liturgical theology at the Boston College Clough School of Theology and Ministry.

Scholars do have ideas about what the Eucharist was generally like in its earliest days. In the first century, these meals took place once a week, often within someone’s home, where the Christian community rearranged the furniture to host the gathering. The church outgrew this arrangement in the second and third centuries, and Christians began to permanently renovate rooms in larger houses to accommodate worship.

Early Christians probably used whatever bread a community normally ate during daily meals for the host, writes Edward Foley in From Age to Age: How Christians Have Celebrated the Eucharist (Liturgical Press). For some communities—especially those with fewer resources—this meant using unleavened bread. Bread and wine may have made up the entirety of a meal, explain Paul F. Bradshaw and Maxwell E. Johnson in The Eucharistic Liturgies: Their Evolution and Interpretation (Liturgical Press). In communities with a more mixed social standing and greater resources, the meal could have included cheese, vegetables, and fish.

The structure of eucharistic gatherings likely reflected the cultural influences of the time. At formal meals in the Greco-Roman world, people reclined on couches along three sides of the room with food in common dishes on low tables in front of them. They would have eaten with their hands. It was common for a deipnon—evening meal—to be followed by a symposion—a celebration—which included wine as both a beverage and a libation. T his symposion would also involve singing, reading, and discourse.

The early Christian Eucharist probably also included prayers from the Jewish tradition. One such prayer Catholics today will recognize is the birkat-ha-mazon—the blessing of the meal. “Almost everywhere from the very early period, the eucharistic prayer would have been improvised— probably in a Jewish model—formulaic, and short,” says Kimberly Belcher, an associate professor of liturgical studies at the University of Notre Dame.

Jewish prayers were improvised based on common formulas (rather than reading from a text), but scholars believe the prayer would have begun something like this: “Blessed are you, Lord, God of the universe,” followed by something that meant: “Blessed are you who give us food,” echoes of which remain in our eucharistic prayer today.

“We don’t have any texts for these, but we know that this acknowledgment of the gifts of creation was there, and this importance of thanksgiving comes down to us,” says Richard McCarron, an associate professor of liturgy at Catholic Theological Union. He notes that when the gospels say Jesus “said the blessing” and “gave thanks” during the Last Supper, these are “shorthand terms for these patterns of prayer.”

Early church documents tell us little about who presided at liturgies, but in Greco-Roman meal practices of the time, “the host of the meal would have been the ordinary leader of any toasts that took place, and, in Christian groups, of the special blessing and sharing of the bread and cup with ritual words toward the end of the eating portion of the meal,” write Carolyn Osiek and Margaret Y. MacDonald in A Woman’s Place: House Churches in Earliest Christianity (Fortress Press).

Christian scriptures provide several accounts of women serving as heads of households, including the mother of John or Mark (Acts 12) and Lydia in Philippi (Acts 16). While we have no definite evidence that these women presided over eucharistic meals, women’s participation and leadership were common in house churches, writes Foley.

In the second century, the writings of Justin Martyr reveal a basic liturgy familiar to Catholics today: scripture readings, followed by discourse by the leader, intercessions, prayers over the bread and wine, and distribution of the Eucharist. Justin’s writing and the Didache—an early church manual thought to date from around the same time—offer some of the first written directions for the liturgy, but they don’t specify who the presider would have been. “It is clear from the earliest years that there is no particular anxiety about the qualifications of leaders of the ritual meals,” write Osiek and MacDonald.

This does not mean the Eucharist was not important to early Christians. In the second and third centuries, some Christians brought home the consecrated bread from their weekly gathering and saved it to break their fast every morning before eating anything else. “That is how crucial it was to their lives,” says Belcher.

Yet Christians “weren’t scrupulous about it in the way that we are now,” Belcher says. “There wasn’t this fear that you would unintentionally do something wrong . . . it wasn’t something that they were afraid to touch or afraid to eat. We don’t start to see that happening until the fourth century and beyond. And they also saw it as something that shed light on their whole lives, not as something that was important because it was divided from their whole life.”

One bread, one body

The history of the Eucharist and our eucharistic practices point to a deeper theological understanding, just as the type of food we eat tells us about our familial and cultural backgrounds. “We can recognize who we are by what is put on the table. We are people who eat and drink bread and wine together,” McCarron says. “The eating and drinking together commit us to one another. We are a part of this whole.”

Early Christians saw the unitive dimension of the Eucharist first in the production of the bread, to which they would have been more connected than we are today. “The simple production of a loaf of bread—you were dependent on the farmers and the agricultural development, you were dependent on the ones who would keep the ovens stoked so you could take the bread” and put it in the communal oven, McCarron says.

The significance of bread is found in the Didache and also in St. Augustine’s sermon to newly baptized Christians:

Remember: Bread doesn’t come from a single grain, but from many. When you received exorcism, you were “ground.” When you were baptized, you were “leavened.” When you received the fire of the Holy Spirit, you were “baked.” Be what you see; receive what you are. . . . In the visible object of bread, many grains are gathered into one just as the faithful (so scripture says) form “a single heart and mind in God” (Acts 4:32).

As communities grew, Christians continued to use bread baked at home for the Eucharist, which they brought in offertory processions. Today, the average Catholic has a far less intense awareness of the underlying spiritual and physical interconnection involved in the Eucharist. While some churches have tried to bring back the practice of having parishioners make the loaves for the host, most parishes utilize commercial, machine-produced wafers that don’t resemble ordinary bread.

“For us, we have to stretch our minds a lot more when a host is being broken and there are 500 of us there receiving individual hosts, versus the communities that saw that the bread that is being broken and shared is bread that is substantial bread,” says McCarron. “ ‘Work of human hands,’ we say—that is kind of hard to see when we rip open a plastic bag and dump 500 hosts into a ciborium.”

Early Christians also had a more vested interest in ensuring they remained unified. “Unity was considered a life-or-death matter,” says Belcher, noting that amid a threat of persecution, early Christians were dependent upon each other across multiple social classes. “Which is why the meal meant for them the unity. . . . For them, the real presence of Christ was also in his presence with them at the meal, not just in the elements that they are eating and drinking.”

Belcher continues on to say, “I wouldn’t say the emphasis we have today is wrong, but we’ve lost a bit of that sense that the Eucharist’s main meaning is the way we are bound together in Christ.” The other name for the Eucharist—communion— emphasizes this meaning.

Like today, only baptized Christians could receive the Eucharist in the early church. Unlike today, members of the community had to reconcile with each other before participating in communion. Eucharistic unity also included a responsibility to ensure that all were fed. Deacons brought the Eucharist to anyone who could not be at the weekly gathering. The head of the household who hosted the Eucharist was also in charge of distributing the weekly offering for the poor.

But the church has never lived out this eucharistic vision perfectly. As Baldovin puts it, “Human beings have always been human beings.” Even though Jesus chose to eat with people who did not meet the social expectations of the time, “not all who followed him seem to have understood his message in quite such a radical way,” write Bradshaw and Johnson.

Early on, many Christian communities mirrored the cultural practice of reclining at a table according to social order, even during eucharistic meals. Friends of hosts or important guests would have been in the dining room, while less-known and poorer people, as well as anyone who arrived late because of their work responsibilities, were “relegated to an open-air atrium,” Foley writes. These people of a lower social standing were sometimes fed worse food, asked to take a handout of food home with them rather than eat it with the rest of the assembly, or not given any food at all.

Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians gives us evidence of this, as he chastises that community: “When you come together, it is not really to eat the Lord’s supper. For when the time comes to eat, each of you proceeds to eat your own supper, and one goes hungry and another becomes drunk” (1 Cor. 11:20–21). To solve this problem, Paul suggests people eat a meal at home before gathering for the Eucharist.

“I sometimes find that a little comforting— that there wasn’t a time we were just getting it right,” says Belcher. “We were always getting it wrong and right.”

The history of the Eucharist and the path to today

In the fourth and fifth centuries, the diverse eucharistic celebrations of the early church came together to produce the basic structure of the Mass we would recognize today. Eucharistic prayers were written down. When Christianity was decriminalized under Constantine in the fourth century, Christians were allowed to celebrate their rituals in public. Eventually, they gathered money to make large structures in which to do so.

Being Christian became a social advantage rather than a disadvantage, and a larger number of less-devoted people now joined the church. As a result, church leaders placed greater emphasis on catechesis in order to communicate the transcendent nature of what happens in the Eucharist. They also encouraged fear and awe when receiving the sacrament.

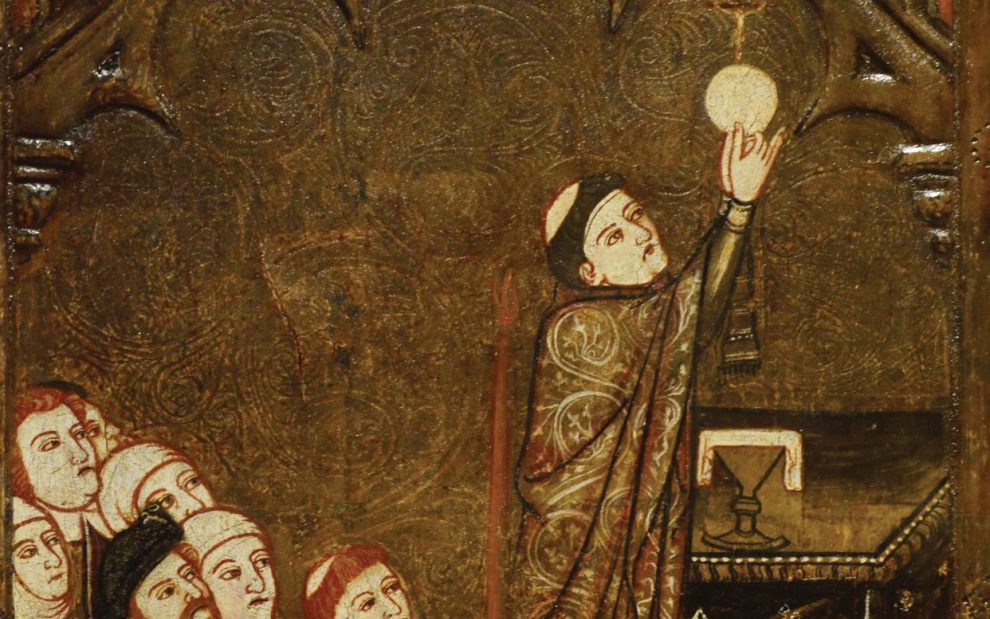

In the ninth century, the first controversies arose about how to express the presence of Christ in the Eucharist. The disagreements came to a boiling point in the 11th century. Around this time, the elevation of the bread and wine during the eucharistic prayer was added to the Mass, and eucharistic adoration developed out of this practice. In the mid-13th century, St. Thomas Aquinas produced his explanation of transubstantiation: “The presence of Christ’s true body and blood in this sacrament cannot be detected by sense, nor understanding, but by faith alone, which rests upon Divine authority.” Today’s Catholic Church still adheres to Aquinas’ explanation.

But not all Christians agreed. During the 16th century Reformation, the presence of Christ in the Eucharist and the meaning of eucharistic sacrifice were two of the biggest controversies. In more recent history, the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s, largely inspired by the early church, made significant changes to the eucharistic liturgy.

A church on a mission

This year, the third year of the Eucharistic Revival, is the “Year of Mission,” with the stated goal of “sharing the gift of our Eucharistic Lord with those on the margins,” according to the Eucharistic Revival website. The “Year of Mission Playbook,” also found on the website, largely emphasizes evangelization and faith formation for those who do not currently have a deep devotion to the Eucharist. Still, plenty of people are marginalized in other ways, such as migrant or refugee communities. They have strong eucharistic devotion, but their needs are often ignored.

When Strassburger went to Brownsville, Texas in 2021, he saw a great need for sacramental ministry to the migrant populations on the border. He and a small team of Jesuits began to fill the gap, and they now celebrate biweekly Masses or communion services at five shelters—three in Mexico and two in the United States—as well as a weekly Mass at a U.S. center for unaccompanied minors. He said this experience has taught him what it means to be a church on a mission.

“What I have encountered in shelters is the church alive and vibrant and well,” he says, “but so often deprived of sacraments because the institutional church isn’t always present where the people of God are.” While a migrant living in a shelter might seek out a nearby parish, “there is something powerful for migrants when the institutional church shows up where they are,” says Strassburger. For migrants such as Maritza Guillen Méndez, these liturgies are the first access to Mass they have had in a long time. With her three children, ages 6 to 15, Guillen Méndez traveled for more than a month from Venezuela to the United States, only to be kidnapped by a cartel and held for 22 days. Guillen Méndez and her children were released—with many of their belongings stolen—into Matamoros, a Mexican city on the Rio Grande, where they stayed for more than seven months. Also stolen was Guillen Méndez’s phone, on which she had registered with the CBP One app (the software migrants use to request an appointment to enter the United States).

While at a shelter in Matamoros, Guillen Méndez learned that the Jesuits were celebrating Mass in a nearby shelter. She attended, and when she explained her situation, they helped her recover her lost CBP One account; she was able to get an appointment to enter the United States on January 4, 2025—just two weeks before the Trump administration shut down the app and all existing appointments were canceled. Both of these services—the celebration of the Mass and the help on her journey—were invaluable for her.

“[The Eucharist] helps me feel at peace and calm,” says Guillen Méndez in a phone interview, with Strassburger translating. “I give thanks to God to have had these opportunities to go to Mass and meet the Jesuits and the help they’ve provided to be able to recover my old registry and get an appointment; it has been like a dream.”

Strassburger describes some interruptions to the Mass that can take place in migrant shelters, such as people in the congregation pointing their phones at him so a family member back home can join them for Mass virtually, or an eruption of cheers because a migrant has just gotten an appointment to enter the United States. “We just try to incarnate our faith in the midst of those environments,” Strassburger says.

He notes that they also incorporate elements of beauty—like gold chalices and liturgical vestments—in their celebrations to point to transcendence. He says he has increased his appreciation of some ancient practices and symbols through these Masses, such as the sensory elevation of incense during a Mass celebrated in a plaza just 10 feet from porta-potties.

“When I think about what it means to reverence the Eucharist, for me, it is not about putting it on display in an ornate monstrance,” says Strassburger. “It is not about maintaining a particular decorum during the celebration of the Eucharist. It is about recognizing the importance it has in the life of the faithful, and I see that importance every time I celebrate Mass in the shelters.”

The contrast between the Eucharistic Revival and the migrant Masses highlights a perennial tension in the church, a tension between what Baldovin describes as the “vertical” and “horizontal” elements of the Eucharist: our connection with God and with one another. The challenge for the church today, as he sees it, is placing adequate emphasis on both pieces.

“The qualms I had about the Eucharistic Revival are that it so concentrates on the presence of the Lord in the consecrated bread and wine—which is true, of course, and adoration has its place,” he says. “But if that happens at the expense of going out and feeding the poor, then you’re in trouble.

This article also appears in the March 2025 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 90, No. 3, pages 10-15). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Wikimedia Commons

Add comment