The United States does not feel like a great place to be a woman right now. I’m not proud of a nation in which 75 million Americans voted for a convicted felon and serial predator over an accomplished, empathetic Black woman. Of Catholic voters, 56 percent who turned out chose Trump, so I’m not feeling great about my church, either. And given that 52 percent of white women voted for a man who is a serial sexual predator, it’s clear that something is deeply wrong with my demographic. Despite decades of feminism, far too many white Catholic women would rather passively uphold an oppressive regime than answer the gospel call to fight injustice.

Just a few days before the election, I finished Shannon K. Evans’ new book, The Mystics Would Like a Word (Convergent Books). Teresa of Ávila, Margery Kempe, Hildegard of Bingen, Julian of Norwich, Thérèse of Lisieux, and Catherine of Siena—we know them in their holy-card manifestations, demure, pious, and pretty (but not too pretty). We associate their spirituality with a rejection of the physical, since women’s bodies have always been a problem for the church. We may even feel uneasy with these saints and mystics, since female spirituality has often been used to shame women who don’t fit the holy card image.

Evans shows us these women as they really were, in their authenticity, complexity, sensuality, and strangeness. The book is divided into six sections, one for each mystic, each section divided into two chapters on what we can learn from these women’s stories. Demure defenders of the patriarchy they certainly were not.

“Trusting yourself doesn’t make you a heretic,” is the title of one chapter about Teresa of Ávila. We know Teresa was a strong woman, a reformer, but her hagiographies usually leave out the fact that she was not beloved by male authorities in her day. An archbishop wrote of her as a “disobedient and contumacious woman who invented wicked doctrines and devotions.”

The reason Teresa was sent to a convent in the first place was that she had been caught behaving inappropriately with a love interest, though we don’t know the exact details. Even today, our society forgives men’s sexual transgressions but punishes women for them.

When Teresa turned to religious life, it wasn’t a rejection of sensuality as such. It was partially to seek freedom. And her experiences of mysticism, once she became a mystic, were erotic, integrating the whole person, body and soul. If anything, Teresa grew into her sensuality. “I think the second half of life was Teresa of Ávila’s sexual prime,” Evans writes. “She just expressed it differently.” Women’s sexuality is often treated as existing only for the purpose of male pleasure and human reproduction, but Teresa contributed to neither of those. Her sensuality was between herself and God.

Margery Kempe, by contrast, experienced the horror side of female sexuality. In “All the Best Prophets Were Mentally Ill,” Evans discusses Margery’s postpartum psychosis and experiences of marital rape. Her mystical experiences and ministry as a preacher were tied to her mentally fragile condition.

This is something we don’t want to admit about saints—some were mentally ill. This is another area where women can’t win. We’re constantly accused of being crazy, but also not allowed to be crazy. Often, we keep our mental illness hidden, knowing we’ll be condemned for it—even though, as Evans points out, there are so many reasons for women to be anxious or depressed. Connecting Margery to her own teen experiences of self-harm, Evans reminds us that being “mad” can also be a form of social resistance.

Especially intriguing is Margery’s choice to recreate herself as a virgin. Typically, I would recoil at this idea. In my late teens, I lived a summer in a religious community of consecrated single women; there, virginity meant purity, and purity meant erasure of sensuality. Women who had been sexually active in the past, whether in marriage or not, talked about a “secondary virginity” in a way that felt self-effacing.

But Evans points to a different angle on Margery’s secondary of celibacy. She’d extricated herself from marital rape, so virginity meant safety, but, Evans writes, it also “meant so much more than not having sex with her spouse anymore; it was a stake in the ground of self-belonging and self-fulfillment.”

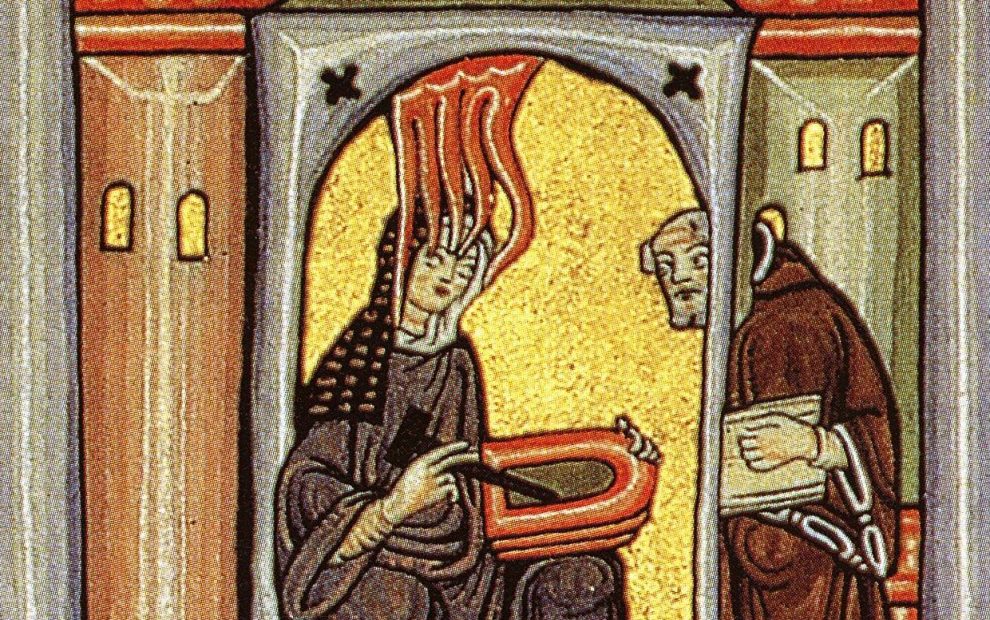

Following the eco-feminist tradition, Evans connects the violation of women with the violation of the Earth. But there’s a saint for creation, too: Hildegard of Bingen, whose “sacramental seeing of the world” is a component in environmental justice. The earth is not secondary to or separate from us. It is a “sacred mirror reflecting our internal reality.”

Hildegard is also the patron saint of artists and writers. With the threat of climate catastrophe exacerbated by a coming regime that will remove our environmental protections, those of us who create need to bear witness. Evans reminds us that sacramental seeing, revealed through art and writing, is needed in troubled times—not just for solace. Art doesn’t have to be escapist. It can empower us to vision a better world. “So get in touch with your inner insurgent, your inner rebel,” writes Evans. “Because we need you to tell us it can be better than this.”

While Hildegard was a woman of the world, mystic Julian of Norwich, by contrast, retreated from the world. She spent much of her life as an anchoress, literally walled in a church. I share with Edgar Allan Poe a horror of tight places, so this is one of my worst nightmares, but for Julian, that small space was freeing. As Ellyn Sanna wrote in an essay on the anchoress tradition, “an anchorage gave a woman something not available to most women in the Middle Ages: what Virginia Woolf called ‘a room of one’s own’—a protected, private space where the creative, spiritual, and intellectual life could flourish.”

Julian, like Hildegard, points us to a better way of seeing, with her theology of God as Mother. Contemporary Catholics who balk at using feminine language for God should be aware that Julian paved the way for this theology centuries ago. The divine feminine was simply a reality she experienced, one of many dimensions of God.

This idea of a feminine God, Evans reminds us, is more than a theological quibble. It is a justice issue. Images of God as exclusively male have been used to prop up oppressive hierarchies that hurt not just women, but men as well. Our images of God guide our ideas of how society should be ordered. The men (and women) who elected Trump would not have done so if their image of God were not rooted in ideas of anger, violence, and oppression.

I was already aware of Teresa, Hildegard, and Julian as subversive figures. But it never occurred to me to think about Thérèse of Lisieux that way. Thérèse, always pictured as sweet and girlish, with her bouquet of roses, with her “little way,” gets used to shame women who are noisy or ambitious.

Evans, apparently, had a similar view on Thérèse. But Thérèse was not naturally docile. She was filled with desires and, yes, ambitions, including the ambition to be a priest. The Women’s Ordination Conference has chosen her as their patron saint, Evans notes.

Thérèse was also sick, dying of tuberculosis, and she knew she would never pursue her ambitions of changing the world. In choosing smallness, did Thérèse, I wonder, take her fate in her own hands, daring to make it her own? Evans invites us to see Thérèse’s “little way” as a creative alternative in a world obsessed with power and prestige.

Smallness can also be resistance. The day after Trump was elected several of my friends posted a picture by Iranian artist Raoof Haghighi, a line drawing of a woman with only empty air where usually breasts and pelvis would be. The sliced off sections of her body lie at her feet. The title of the art is “Just take them and leave me alone!” On the artist’s Instagram pages, multiple women commented that it was the most powerful image they had ever seen.

I keep thinking about this image in connection with Evans’ stories about self-harm and myths about women turning into things. We don’t feel safe in our bodies. Sometimes punishing our bodies can feel like our only agency. But what if we could become smaller, less visible? It doesn’t have to mean powerlessness. Invisibility can be a superpower. Spies use stealth.

Maybe the most intriguing part of The Mystics Would Like a Word is Evans’ discussion of my own patron saint, Catherine of Siena. I chose her at a time of aggressive piety when I felt I needed to self-flagellate to be holy, or at least seem holy. As I was vain, arrogant, and argumentative, I felt a humble, devout woman like Catherine could put me in my place. (Evans notes that she also chose her patron saint, Thérèse, because of their differences.)

Catherine lived alongside death and illness. Evans writes about her own experience of nearly dying of sepsis, and the “existential terror” of that experience. Existential terror, she notes, sounds like a bad thing, but what if it’s healthy? We have to face that terror, and Catherine did, head-on, caring for those whose infirmity made them seem monstrous to society.

But she wasn’t perfect. She didn’t delight in her work, she hated it. So, Evans writes, Catherine forced herself to confront her own revulsion by picking up a bowl of water she’d used to clean a woman’s festering wound—and drinking it.

As it turns out, I have more in common with Catherine than I realized. Not because I care for the poor or engage in extreme acts to confront my own revulsion. But this need to look death and terror in the face is what drives my art. It’s why I read and write body-horror poems. I chose the right patron after all.

I also feel a kinship to Catherine because she was messed up in a lot of ways. Her extreme fasting was probably anorexia. She eventually lost the ability to chew and swallow and convinced herself this was punishment for earlier gluttony. This isn’t piety; it’s mental illness. Knowing this makes me feel weirdly reassured, since I’ve never found that even keel women are supposed to have, the cheery middle ground between vanity and self-loathing.

The women mystics can inspire us to to act bravely in the world. They are not hovering above us in an ethereal realm, indifferent to our struggles. They shared many of them. Thanks to Evans’ book, I have a better understanding of these women as our allies, who can help us find ways to survive, create, challenge injustice, and envision a better world.

I am grateful for this book, for the chance to find new subversive sisters who can inspire us to act boldly and love deeply and who model a different, braver way to be a Catholic woman in the world today. If we read their stories and feel ashamed, maybe it’s a good shame. Maybe it will spur us to do better.

Image: Wikimedia Commons, Hildegard von Bingen receives a vision

Add comment