The abbot traced a cross on my forehead with his thumb. “Julia Hildegard, be sealed with the gift of the Holy Spirit.” Hildegard of Bingen had come to my mind as a natural choice for a patron saint well before I made the decision to be received and confirmed in the Catholic Church. Yet when I first heard of this multitalented 12th-century German abbess, I could not have imagined the many ways that she would become a companion on my meandering journey.

I first met Hildegard, the first non-anonymous composer in the Western musical tradition, in a college course in music history. (The professor gleefully told his female students, “You were first!”)

Hildegard continued to haunt my studies on random occasions, as I gradually became acquainted with this respected leader whose accomplishments included founding two abbeys and undertaking four preaching tours. She was a prolific writer, whose expertise covered a range of subjects vast enough to include cosmic visions, music, morality, ecology, diagnostics, and herbal medicine. She was also a thinker whose interests defied easy categorization.

Having first known her as an artist, I also came to realize how familiar she was with the science of her day, engaging with contemporary understandings a century before Thomas Aquinas did. Hildegard’s view of an ordered universe deeply rooted in its creator and humanity’s deeply integrated place within it contains much wisdom for our time. Her theology is at the same time orthodox and innovative, transcendent and earthy, rational and mystical, offering both/ands for a painfully polarized world.

One of the things I love about the Catholic tradition is that there has long been much room within it for both reason and mystery. Having a great personal affinity for both, I find something of a kindred spirit in Hildegard, who embodied the same duality. Both the confidence in speaking her mind and the self-deprecating tendencies that come out in Hildegard’s correspondence demonstrate an internal paradox that resonates strongly with me.

Already as a child, I saw great things of wonder which my tongue could never have given expression to, if God’s spirit hadn’t taught me to believe.Hildegard of Bingen

Here is a woman of deep faith and deep doubts. The courage that she showed in voicing her insecurities as well as her strong convictions gives me hope that I, too, can contribute valuable insights in and through my self-doubts as well as the times when I feel most eloquent and assured of my rightness. Maybe I am even learning right along with Hildegard of the need, in either case, to turn from self-obsession toward a healthy humility.

Because of these connections it was easy to name Hildegard as a spiritual companion, but there was one thing I was never quite sure of: Is she a saint, or isn’t she? Hildegard’s status remains ambiguous. Though not officially canonized, she has been revered as a saint for centuries and has a feast day on the church calendar.

This is true not only of her ecclesiastical status; her life and character lend themselves to a wide range of interpretations. Some point to her refusal to dig up the body of an excommunicated man who she believed had died reconciled to God—a decision that resulted in her own excommunication for a time—as a model of prophetic dissent. Others point to the many letters she wrote seeking validation from other church leaders as an example of humble obedience. I see all of this as evidence of her complexity as a person who is not easily boxed into any ideology.

Hildegard’s ambiguity makes her an appropriate guide on my own journey, which has been characterized by in-betweenness and pilgrimage in various ways, most recently as I brought my Mennonite heritage into communion with the Catholic Church. Hildegard’s honest self-awareness and genius for integrating ideas helped show me the possibility of living such a duality and the contribution it may yet make in this church I now call home. Her example helps me to articulate what I hope I am also becoming: a complex woman of conviction and questions, reconciling differences and pointing to the connectedness of all things.

This article also appears in the February 2012 issue of U.S. Catholic (pages 63-64). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

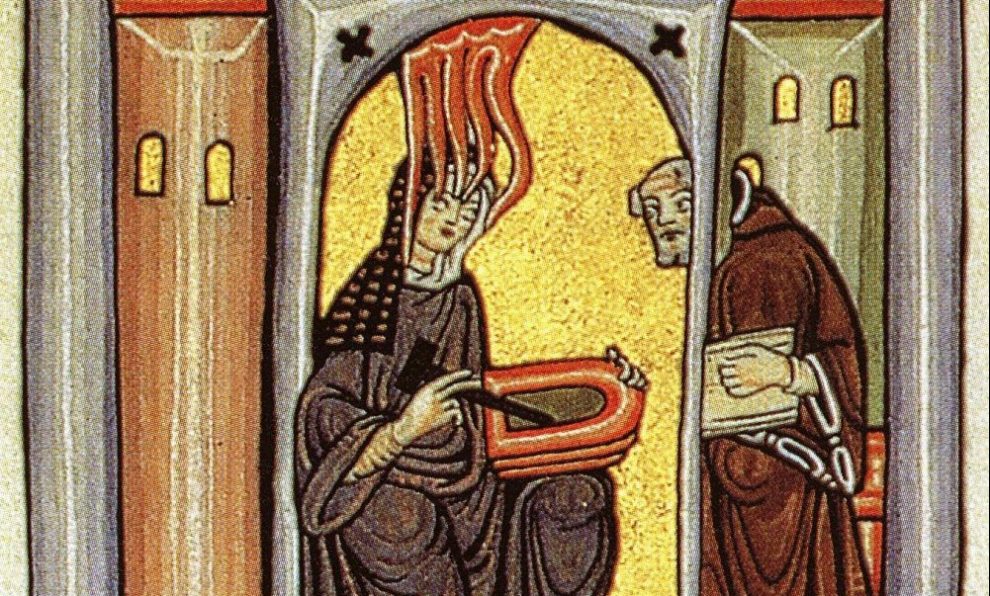

Image: Miniature from the Rupertsberger Codex des Liber Scivias.

Add comment