Sounding Board is one person’s take on a many-sided subject and does not necessarily reflect the opinions of U.S. Catholic, its editors, or the Claretians.

The modest, rural Catholic church on a state highway rarely had more than 40 cars in the parking lot. But on Fridays during Lent, at one point in time vehicles crowded every available space and nearby patch of grass. Parishioners, extended family, and visitors flocked to the parish, not just for fellowship and sharing the fruits of God’s great Earth—Lake Erie fish caught and fried by members of the men’s club and donated baked goods. They also came for what poured out of two taps affixed to a red Igloo cooler: free beer.

Although a new pastor eventually ended that practice (encouraging instead BYOB), there are many other opportunities to drink with Father and friends both at this parish and at countless others across the country—family picnics, adult faith formation dinners, casino nights, festivals, Oktoberfest, and, of course, Theology on Tap.

Although alcohol is the third leading preventable cause of death in the United States, consumption of it is not only ubiquitous in parish life, “Catholic drinking” is also romanticized, glorified, and joked about. Rather than offering an alternative to a pro-alcohol culture that runs counter to core social teachings on human dignity, the sanctity of families, and the common good, punchlines proliferate, such as the one about a priest pulled over for drunk driving. Father claims to have been drinking only water until the officer points to an empty wine bottle on the passenger seat. “Well,” responds Father, hearkening to Jesus’ miracle at Cana, “he’s done it again.”

Several studies document significant increases in substance addiction in the United States over the last few years, and alcohol sales contribute to a $284 billion-dollar industry. The time has come for Catholics to swallow their pride about being the “cool Christians” who drink. The church must offer improved catechesis, inclusive parish-level discussion about drinking, and better support not only for those recovering from addiction but also for individuals and families unsure what constitutes abuse of alcohol and other indulgences.

“[Alcohol], gambling, and tech addictions have become so normalized in American culture that now people can’t even identify that they have an addiction, compulsion, or unhealthy attachment to these things,” says Scott Weeman, who has recovered from addiction and in 2017 founded the nonprofit ministry Catholics in Recovery (CIR).

To be fair, Catholic teaching on the vice of gluttony—all forms of overindulgence—and the corollary virtue of temperance can be confusing. In the Catholic tradition, alcohol, especially wine, is not only praised as a gift from God but is also central to our most sacred celebration, the Eucharist. Both in past centuries and today, monasteries have sustained their communities by producing and selling beer and wine. While the catechism clearly defines driving under the influence as a grave sin, its teachings about temperance are highly nuanced. Perhaps the clearest teaching comes from St. Thomas Aquinas, who wrote in Summa Theologica that “drunkenness is a mortal sin.”

Christie Walker, a podcaster and social media influencer who offers help to women as a Catholic sobriety coach, is particularly alarmed by the pro-drinking “Mommy Juice” trend. “It infuriates me and disappoints me, because it’s like saying you’re not strong enough to be a mom. So here’s some alcohol, and that’s going to make you better,” she says.

What might seem like innocent attempts to communicate lightheartedness and welcome via alcohol, such as naming the men’s club “Whiskey and the Word,” in fact perpetuates a message of secular culture that joy and fellowship require artificial enhancement. “The centrality of drinking is not necessary,” says Weeman. “I think it sidesteps a lot of spiritual growth.”

The church can learn much from people who have experienced addiction and who have remained or returned to the faith because of their powerful experiences of God’s mercy in the sacraments, especially confession. Yet their efforts to bring to Catholic parishes programs of education, prevention, and rehabilitation are often thwarted by a persistent culture of avoiding what Weeman calls the “messiness” of mercy. His organization supports regular faith-based fellowship meetings—meant to supplement recovery therapy and other 12-step programs—for people experiencing addiction and their families at 100 parishes across the United States, Canada, and Mexico and hosts 15 online meetings per month.

While Weeman says CIR is making progress toward a goal of groups in every U.S. diocese, offering hope to Catholics battling all sorts of addictions, that dream is far from reality. He tells the story of one priest who worried that Catholic recovery meetings—similar to Alcoholics Anonymous but incorporating prayer, scripture, and the “good news that God can bring about healing”—would attract “unwanted addicts” to his parish. To that, Weeman could only reply, “Father, you need to be aware that they are already here.”

When parish leaders ignore the pervasiveness of substance abuse, they demonstrate a lack of humility, Weeman says. “It’s always like it’s someone else that needs this, but not me,” he says. “When everyone adopts that attitude, then it adds to a culture of stigma around healing.”

When parishes tacitly or directly condone drinking while at the same time offloading responsibility for any negative consequences to others, they fail in the mission of mercy. “Within the church today, we oftentimes will delegate healing to other secular groups or institutions,” Weeman says. “We’ve gotten away from getting involved in the mess of healing. I think that we would rather hide, and this is exactly what the devil wants us to be doing, to hide ourselves, to lie, to be dishonest, to deny that there is a problem that we need to bring to Jesus.”

“[Addictions] are different symptoms of the same spiritual malady,” he says. “The pursuit of these behaviors is at its core a pursuit of fulfillment. We are driven to fill ourselves in a way that only God can.”

Weeman envisions a time when the church embraces recovery programs as opportunities for evangelization. He points to the success of Celebrate Recovery, a fellowship offered in 30,000 Protestant churches. “We lose a lot of Catholics to non-Catholic Christian churches because when [people experiencing addiction] find the miracle of their addiction being relieved from them in a Christian church, naturally, they begin worshipping there,” he says.

Because Catholics are called to be “atypical” people by virtue of our baptism, we are called to confront a culture that promotes indulgence. When parish programming educates, supports, and forgives with openness and mercy, it erases the stigma of addiction. This benefits everyone, not just those who are struggling to resist overuse and the damage it wreaks on relationships and society. No one—even those who have recovered from addiction—expects alcohol to be extracted from every parish event, but refraining from the punchlines and emphasizing of liquid spirits is a good place to start. Something as simple as offering better nonalcoholic adult beverages—such as nonalcoholic beer, wine, and mocktails—when drinks are served would signal a more compassionate, more countercultural welcome to all.

Perhaps Pope Francis said it best when in 2014 he addressed a meeting of drug enforcement agencies. Catholics should do more than “just say no” to addictive substances and behaviors. We must offer counter-witness to a permissive culture with radical forgiveness and acceptance.

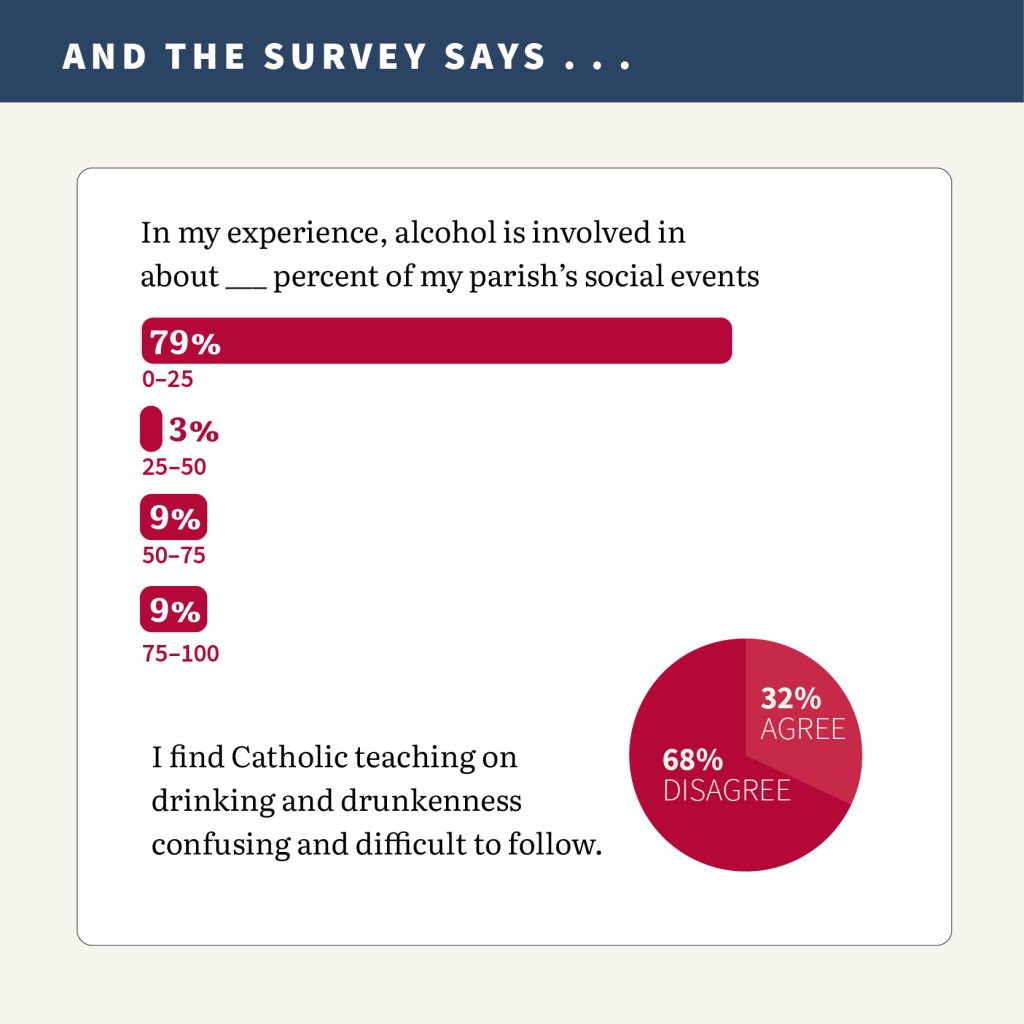

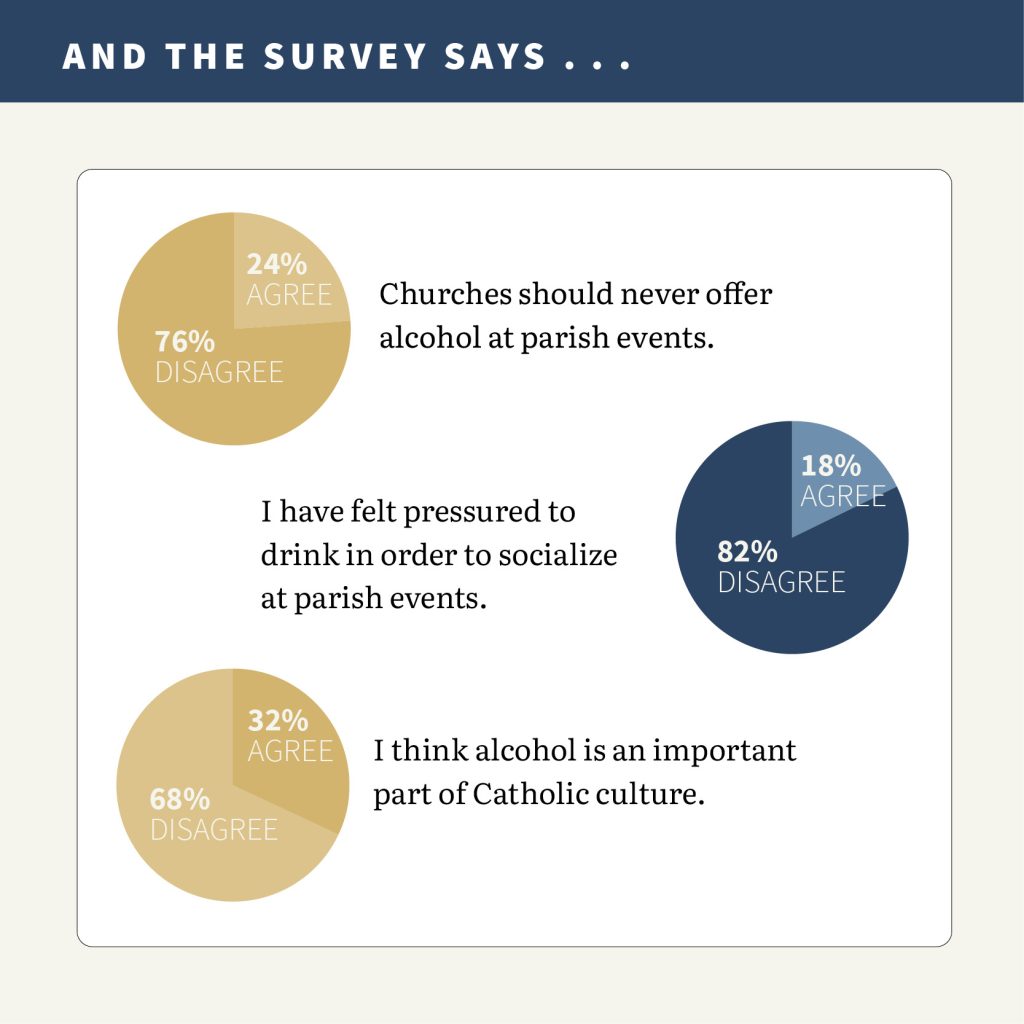

Results are based on survey responses from 33 uscatholic.org visitors.

This article also appears in the February 2024 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 89, No. 2, pages 27-30). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Unsplash/Sergio Alves Santos

Add comment