My friend and I were eating at a restaurant in South Bend, Indiana when someone called the police on us. She accused us of scaring her 8-year-old daughter. The three white police officers who showed up kept us grounded until they had gone through the surveillance video. Then they released us with a rather flimsy apology. “She is just a child, and children get scared.”

While the little girl’s innocence is not in doubt, there is nevertheless the possibility that she has internalized much of the racial bias of the adults in her life. This is very concerning. Citing recent research, Robin DiAngelo explains in her 2018 book White Fragility (Beacon Press) that “children are vastly more sophisticated in their awareness of racial hierarchies than most people believe.” Ibrahim Kendi is right to insist that an antiracist baby is bred, not born!

Yet the issue is not whether the woman who called the police on us is racist; it is that racism is still a thing in the United States and that the experience of racism is always traumatic.

While I know that it is quite depressing to write about racism, especially on Easter Sunday, the sad reality is that racial minority immigrants in the U.S. continue to cope with explicit and implicit forms of racism.

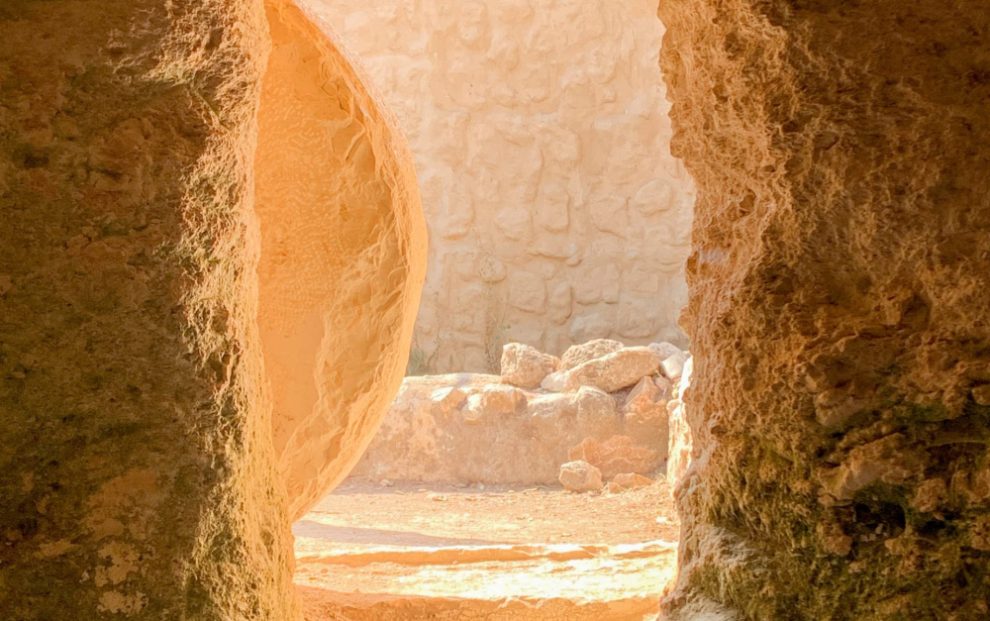

But then, I don’t just want to write about racism and immigrants’ trauma. I also want to write about hope. Easter means hope. As Christians, the resurrection of Jesus is the most important event ever. It is the foundation of our hope.

For immigrants, however, Jesus’ rising from the dead is not just hope for resurrection at the end of time. It is also the power and inspiration to rise daily above racial slurs and the growing anti-immigration rhetoric, which according to a recent publication by the American Psychological Association, has been on the increase since at least 2016.

While, since the end of the civil rights movement, racism has become more subtle than overt, it still exists. Although, for instance, the era of lynching might be over, this does not mean that the racism that powered it is yet to be completely eradicated. Two years ago, Pope Francis described racism as a virus that knows how to mutate and hide. This is why, according to him, it never entirely disappears but lurks around, waiting to strike.

It usually does not take too long before new immigrants to the U.S. have their first experience of racism. Portia, the friend who was with me at the restaurant, was barely three months in the U.S. when she had this first “real” experience of racism. Five minutes after the cops departed, Portia was still trying to process what we had just experienced and what could have happened.

“What just happened?”

Her question came in a whisper. She was breathing heavily; her voice was shaky.

“Isn’t this what we see every day on the news? The shootings and the killing of unarmed Black people? What if there were no surveillance cameras?”

She was evidently traumatized. The next day, she was reluctant to go to work. The many friendly faces in her office were not so friendly in the nightmare that woke her up at 3 a.m. The white cops came back. This time they were brandishing weapons, and just as they were about to shoot at her, she woke up, sweating profusely.

While she felt too weak to leave her bed that morning, she knew she had to be at work at 9 a.m. How was she to tell her white boss that she almost got arrested for the “crime” of scaring a little white kid simply by the color of her skin? She is not confident that her boss will understand. She is still on probation at her employment. Missing work is not an option. Like many newly arrived immigrants in America, she must rise despite her anxieties.

The cheering news is that despite our many challenges as immigrants, we are far from hopeless. We have hope. The kind of “Easter” hope Maya Angelou celebrates in her 1988 poem, “Still I Rise.”

“Still I Rise” is a poem about hope and resilience. For me, it is an Easter poem. The resurrection theme throughout the poem is unmistakable. “I will rise” or simply “I rise” occurs eight times in the poem. Neither “bitter, twisted lies” nor “nights of terror and fear” can keep her down. She is like the air that rises, no matter what.

As Black womanist theologian Shawn Copeland rightly explains the themes of resurrection and hope are intertwined in the Christian imagination. As a Christian, Angelou obviously understood that the resurrection of Christ and our future resurrection is at the heart of Christian hope. But then, as African American, she is a child of resilience, the product of the long and admirable struggle of Black bodies and souls throughout the eras of slavery and segregation and beyond. Indeed, for people who have been shouted down, hacked down, enslaved, oppressed, marginalized, and disfranchised for so many years, hope is resilience. Hope is the ability to rise no matter how often you are put down.

Angelou’s poem does not speak to the descendants of enslaved people only, but to Black immigrants like Portia and me, and indeed all immigrants. We are the “new inheritors of a new racism,” as Martin Baker describes immigrants to Britain in an article in 1979.

For immigrants, to survive in America is to make resilience a habit—nay, a culture, a spirituality even. It is to rise above microaggressions and even intentional racial slurs people randomly throw at you, intending to demoralize you. It is not to be deterred by the rising anti-immigration rhetoric on some major national TV stations, especially those that label undocumented immigrants as illegals and call for their deportation.

For the immigrant student, surviving is not to stop speaking up in class and speaking your truth even though your classmates constantly mock your accent or even when people try to make you feel incomprehensible and unintelligent.

For the immigrant who is still getting integrated into the American workforce like Portia, it is working twice as hard as everyone else while having to ignore unfounded accusations about immigrants stealing jobs otherwise meant for Americans.

Easter means hope and resilience. The story of Easter is God’s message of hope to all immigrants.

The American church must continue to proclaim this message of hope to immigrants. However, true solidarity with immigrants goes beyond welcoming immigrants into the church space. It requires ensuring that the church is indeed a safe space for all minorities, and it requires that the church gets more involved in advocacy for their unique plight.

Image: Unsplash/Pisit Heng

Add comment