On a gray spring day, I enter the hospice unit with three other women. Following cues from the nurses, we quietly approach the room of an old woman lying unconscious in bed. Beside her sit her two daughters, holding hands and weeping. They nod as we enter the room. They have called us to sing for their mother as she approaches death. We face one another, and our leader begins a simple song: “Peace before you, peace behind you, peace under your feet. Peace within you, peace over you, let all around you be peace.” We sing first in unison, then in a gentle three-part harmony.

The Safe Passage Singers is a group of mostly Generation X and Millennial women in Dubuque, Iowa who gather to sing for people undergoing major life transitions such as giving birth, moving, retiring, and dying. The group was started in 2014 by Mary Kay McDermott, a Catholic Worker, farmer, and mother of two. One day, she heard a radio interview with members of the Threshold Choir, a national organization of volunteers who sing songs of comfort to the dying. “Hearing about this, I was brought to tears. It was a path to accompany people in vulnerable times I didn’t know existed. My friend and I started a group in Dubuque, first gathering on our own, then singing for others,” she says. While the Threshold Choir only sings to dying people, McDermott’s group wants to sing for people undergoing various life transitions.

The Threshold Choir is not associated with any faith tradition, and its growing popularity marks an increase in the number of people seeking to change the conversation around death from denial to acceptance. Indeed, there is a growing number of people who are seeking to make sense of death and dying outside of their specific faith traditions, particularly through the arts, whether this be through making music, creating an altar of loved ones, or writing poetry.

Work of mercy

An experienced choral singer who studied music therapy, McDermott feels called to use her talents to serve others. “On a basic Christian level, I believe we must share the gifts we have received. It’s a work of mercy,” she says. “We come as strangers, and we feel grateful to be welcomed into sacred moments of people’s lives. We have been present and singing at the moment when someone dies. Emotion rises, which is why we never sing alone—we have three to five people so when we’re not strong, we can lean on the group for support.”

Some people grow uncomfortable when they learn of the Safe Passage Singers. “A college student once asked me how I could sing in such a sad situation,” McDermott says. “But St. Benedict said we should keep death before our eyes always. I try to do that in many ways.”

For most of us in the United States, death is a reality we would rather deny, even as the news abounds with stories of mass shootings and ongoing death from the pandemic. Unlike many other countries, the United States has no day officially devoted to remembering our dead.

In the medical field, the death of a patient is considered a failure. Some engineers in the technology industry claim we might someday defeat death by growing new organs in laboratories or uploading our consciousness into computers. But the human mortality rate remains 100 percent. In a society where many lack the vocabulary, the arts and cultural rituals provide a way to engage with this universal experience.

St. Benedict said we should keep death before our eyes always. I try to do that in many ways.

Mary Kay McDermott

“In the United States, we’ve been separated from what it looks like to lose an animal or person. We’ve created funerals where we let someone else bury the dead,” McDermott says. “I think seeing ourselves as separate from nature leads us to fear and deny death. When you live on a farm, you see plants that come to life and grow but then die after the frost. You might see a monarch caterpillar your son brings into the house that doesn’t come to full life. I’ve lost a lot of my bees. Overwintering them is hard, and pesticide use from the farms adjacent to ours is a problem. Recently our dairy cow got sick with pneumonia, and we had to bury her.”

Jan Booth, an end-of-life nurse and advocate in Boulder, Colorado and codirector of the Threshold Choir, agrees that people in the United States have become disturbingly disconnected from the reality of death. “Until 60 or 70 years ago, most people died at home in a multigenerational setting. There weren’t options for extending life,” she says. “There was reticence and grief, of course. But we saw death more often. Modern medicine has brought wonderful advances to reverse disease. The unintended consequence is we are not sure what dying is anymore.”

Recently, however, Booth has observed a cultural shift: “More people at a grassroots level are realizing there’s something wrong. They’re asking how we can show up for our own families and communities, how we can change the dynamic from seeing death as a failure to seeing it as a part of life.”

Commemoration and celebration

While many remain hesitant to grapple with mortality, there are spaces where it is acknowledged and even celebrated. Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead), an ancient Mexican tradition with Indigenous roots, is celebrated annually in conjunction with the Catholic feast days of All Saints and All Souls. It involves making altars to honor deceased loved ones (often with photos and treasured objects), cooking and sharing their favorite foods, and in some regions of Mexico taking part in a certain amount of revelry and mockery. In the United States, the day’s popularity now extends beyond the Latino/a community.

Lupita Castañeda-Liles, a 15-year-old from San José, California, has celebrated Día de los Muertos since early childhood. “I remember seeing a picture of my great-grandmother and crying because I never got the chance to meet her,” she says. “I was very distraught. My mother said it’s important to grieve the departure of loved ones, to honor that they are in another realm. But in time my perspective changed from a day of grieving to a day of celebrating and honoring the dead.”

While Castañeda-Liles has always appreciated the celebration in her home, she was especially moved last year when the whole student body of her Catholic high school observed Día de los Muertos. “It brought joy and peace to realize that Day of the Dead isn’t just celebrated by Latinos,” she says. “Death is a universal experience everyone should honor. It was great to see my whole school come together on one special day, share the stories of our loved ones’ passings, discuss foods they liked—it was able to really break down the boundaries that our society unfortunately places on us.”

Some in the Latino/a community, however, are concerned about cultural appropriation and commercialization of Día de los Muertos. “The day is becoming commercialized, in the United States and in Mexico,” says Vanessa “Cueponi Cihuatl” Espinoza, a high school Spanish teacher in West Liberty, Iowa, where 80 percent of the students are from a Latino/a background. “Since [the Disney movie] Coco came out, there’s Day of the Dead tourism. Tourists come to Mexico wanting to experience this tradition. But these are my ancestors’ graves. I don’t want tourists coming and taking a picture of them without knowing the stories. They want to experience the magic. I think there are things that should be protected. Why is Target selling Día de los Muertos stuff? In the colonial period, when my ancestors were murdered for celebrating this holiday, they were called satanic.”

Espinoza believes that Día de los Muertos should only be celebrated by people within the cultures where it originated. “It’s an intimate day. I may sound like a gatekeeper, but we have been satanizado [satanized] for so long. The White House had a Day of the Dead celebration, and the symbolism was not correct,” she says, mentioning that it included an image of Our Lady of Guadalupe, who is not associated with Día de los Muertos. “The people who celebrate this tradition know each symbol, the connection to Mother Earth.”

When teaching her students about Día de los Muertos, Espinoza always mentions monarch butterflies, which traditionally are believed to be returning loved ones.

“In class we talk about the environment, butterflies, the Mexican climate activists who’ve been killed. I get my students thinking about various themes, not just death and dying but what kinds of ancestors we want to be,” Espinoza says, adding that she has partnered with the organization Milkweed Matters to promote conservation efforts. “I’d say if people [who are not Indigenous Mexicans] want to celebrate Day of the Dead, they should learn about it but also take some action. Help preserve the butterflies. Put milkweed in your garden.”

Evelyn Nadeau, a Spanish professor at Clarke University in Dubuque, Iowa, believes that Día de los Muertos can be universally celebrated if everyone is respectful. “In the United States, we need a universal way to stay connected to those who have passed,” she says. “Why not develop a healthy attitude and be more playful, have the sugar skull with your name on it? The danger is if someone for whom it’s not an authentic celebration adopts it and then says, ‘This is how it should be done.’ It’s OK to adapt something, but be aware you’ve adapted it.”

For Sandra Marines, a receptionist at Saint Pius V Church in Pilsen, a predominantly Mexican neighborhood of Chicago, Día de los Muertos has increased in importance since she migrated from Michoacán, a western state in Mexico, 20 years ago. “My parents were not particularly religious, so I actually learned more about Mexican traditions here in the United States by working with people who’ve come here from different Mexican states,” she says.

My mother said it’s important to grieve the departure of loved ones, to honor that they are in another realm.Lupita Castañeda-Liles

Every year Marines makes a large altar in the parish hall and sources many materials such as colorful tissue paper, paschal candles, incense, and sugar skulls from Mexico. “I always decorate the parish office so that people are aware of the time we are celebrating,” she says. “We explain to the children that it is a time of happiness because our loved ones are in the kingdom of God. It’s lovely when people who no longer celebrate the traditions show up to the office and see the decorations. We remind them to keep celebrating these customs, to not leave them behind.”

Like Nadeau, Marines finds that Día de los Muertos rituals can be healing for those who suffer losses that go unacknowledged by wider society. “Three years ago, my older daughter had a miscarriage. She could not get over it,” she says. “She saw the altar and said, ‘What photo can I put of my baby? She was a 3-month-old fetus.’ I asked, ‘How do you imagine her?’ She said she imagined the baby as a butterfly. She put a picture of a butterfly on the altar, praying to help it reach the kingdom of God.”

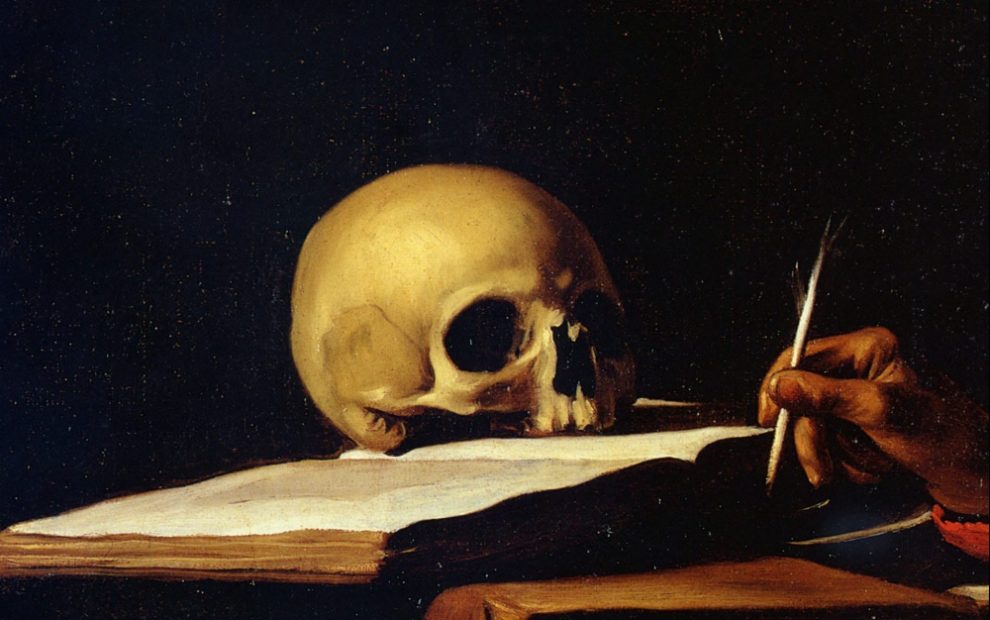

Marines is happy to see Día de los Muertos being more widely adopted by mainstream culture, but she wants to make sure it is understood correctly. “Some, perhaps due to a lack of information, say it’s witchcraft. They don’t realize it’s spiritual and religious. There are even some within the church who see the skulls as diabolic. But really that’s just our bodies. We’re all going to end up as skeletons,” she says.

Naming the unnamable

Like death in general, infant mortality is not frequently mentioned in U.S. public discourse. But with 5.4 deaths occurring for every 1,000 live births, it is a painful reality for many parents. Joyelle McSweeney, an award-winning poet and professor of English at the University of Notre Dame, experienced the death of her daughter Arachne in 2017.

“She was born with an unexpected birth defect and flown to a NICU in Indianapolis. She lived for 13 days and then died. She opened her eyes once,” says McSweeney. “She couldn’t breathe. I never saw her face until they took her off the ventilator and let her go. The shock was intense. At the same time, we had a 7-year-old and a 10-year-old. Somehow, we had to make them feel like the world would keep spinning.”

In the United States, we need a universal way to stay connected to those who have passed.Evelyn Nadeau

At the time of her daughter’s death, McSweeney had written a book of poetry entitled Toxicon, dealing with human-caused catastrophes in the natural world. “On varnishing days / toxic chemicals lick at battle scenes, the storm at sea / intensifies,” she writes in a sonnet sequence entitled “Toxic Sonnets.” The book was inspired by her experience of Hurricane Katrina.

“I came of age as a poet living in Alabama during Katrina,” McSweeney says. “I realized every natural catastrophe is man-made. We know with climate change that disasters are becoming more frequent due to human activities. I’ve always been fascinated by small and large manifestations of catastrophe. Toxicon was alert to those things—novel viruses moving around the world on global distribution chains well before COVID-19. I was learning about nuclear contamination in Fallujah, Iraq causing birth defects.”

When McSweeney suffered the personal catastrophe of her daughter’s death, she found some relief in the coming of winter. But when spring’s beauty arrived, her grief became anger. In the span of a few weeks, she wrote another book of poetry about the loss of her daughter. “I wrote in a grief-stricken rage against spring,” she says. “Demeter strikes a deal with Hades that Persephone would come back in the spring. I thought I’d get that deal. When spring came without her, I was enraged.”

The book, which was published in 2020 with Toxicon by Nightboat Books as Toxicon and Arachne, transforms unspeakable grief into spoken language:

I wept / loudest when your / respirator stopped / pounding in my ear like / money trying / to build a high rise / every afternoon / and every morning / and send it carombing / in the skies above Florida / to sell hamburgers and glorify the Boomers how it / chevied upon air til it / shiv’d like a Challenger / and took both paths at once / and took both exit ramps / all the way down.

“We say there are no words for certain experiences, but the human brain reaches out for words, extending a hand in the dark. An extremely traumatic experience reorients your relationship to words. They have to be reached for. They don’t just come,” says McSweeney, who adds that her Catholic faith has always informed her poetics. “When you are raised Catholic, the amount of information communicated through image and art is intense.”

Arachne is buried in a section of Notre Dame’s cemetery devoted specifically to babies. Today, McSweeney does not mention her experience when teaching or when asked how many children she has. However, the publication of her book—which contributed to her reception of a MacArthur Foundation Fellows Program Genius Grant and a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation fellowship—has opened a space for her to share her story.

“Talking about Arachne is a good thing for me. I want as much time with her as possible. Reading these poems is a way to have her in the world,” says McSweeney, adding that the experience has solidified her commitment to poetry—particularly poetry with an experimental, avant-garde approach.

“When you’re moving in the dark, trying to figure out where to put your foot, poetry becomes a foothold,” McSweeney says. “And it isn’t just soothing poetry. André Breton said, ‘Beauty will be convulsive or will not be at all.’ It’s a catechism of art that came into my ear as I watched my baby convulsing in the NICU. I was in an extreme situation, and extreme art presented itself as a foothold to keep going, much like prayer. It let me prepare for her death. Rather than pushing me toward a more mild or consoling model of poetry, this loss reaffirmed my faith in avant-garde, extreme literature that helps me understand the extremity of what happened.”

It’s a clarifying moment when you recognize you don’t have forever with someone or when you realize you don’t know when your own death.Jan Booth

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the monkeypox outbreak, and the plague of violence have compelled us to think about death. While our first reaction may be fear, our faith encourages us to aim for greater acceptance of life’s finitude. “There are developmental opportunities at the end of life—a chance of a life review, a chance to see coherence and cohesion, to forgive and let go, to experience love and gratitude,” says Booth. “It’s a clarifying moment when you recognize you don’t have forever with someone or when you realize you don’t know when your own death will be. There’s a chance to ask, ‘What are my priorities? How can I live a life that is more meaningful, with more kindness for myself and others?’ ”

McDermott mentions that while the pandemic has prevented the Safe Passage Singers from visiting hospice facilities for now, they have managed to sing to people through their windows or over the phone. “As a Christian, I believe there is darkness before light,” she says. “I think those sensitive moments of transition or darkness or grief in our life are also moments of rejoicing . . . not always for the person left behind but for the person dying. We’re holding people in a dark space but celebrating the light that is to come.”

This article also appears in the November 2022 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 87, No. 11, pages 10-15). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Wikimedia Commons/detail from Saint Jerome Writing, Caravaggio, 1605.

Add comment