On his apostolic visit to the United States in September 2015, Pope Francis amplified the work of four Americans who struggled with the status quo of their times: Dorothy Day, Martin Luther King Jr., Abraham Lincoln, and Thomas Merton. In referencing these individuals, Pope Francis intentionally addressed America’s original sins—racism, anti-Blackness, and white supremacy. He described Merton as “a man of prayer, a thinker who challenged the certitudes of his time, and opened new horizons for souls and for the Church . . . a man of dialogue, a promoter of peace between peoples and religions.”

I knew Merton was a man of prayer, but there was obviously more to this monk in a white body, whose life coincided with the first 10 years of my lived experience.

People born with white bodies do not inherently embody the behaviors and beliefs of their societies. Just as toddlers begin using the word no as an expression of their individuality, the young observe acts of omission and commission and the responses of others. These are normal practices of human development. What is abnormal is how those responses teach them to ignore injustices endured by people of color. Not acknowledging these injustices, they go on whitewashing truth and denying the privilege afforded them because of their whiteness.

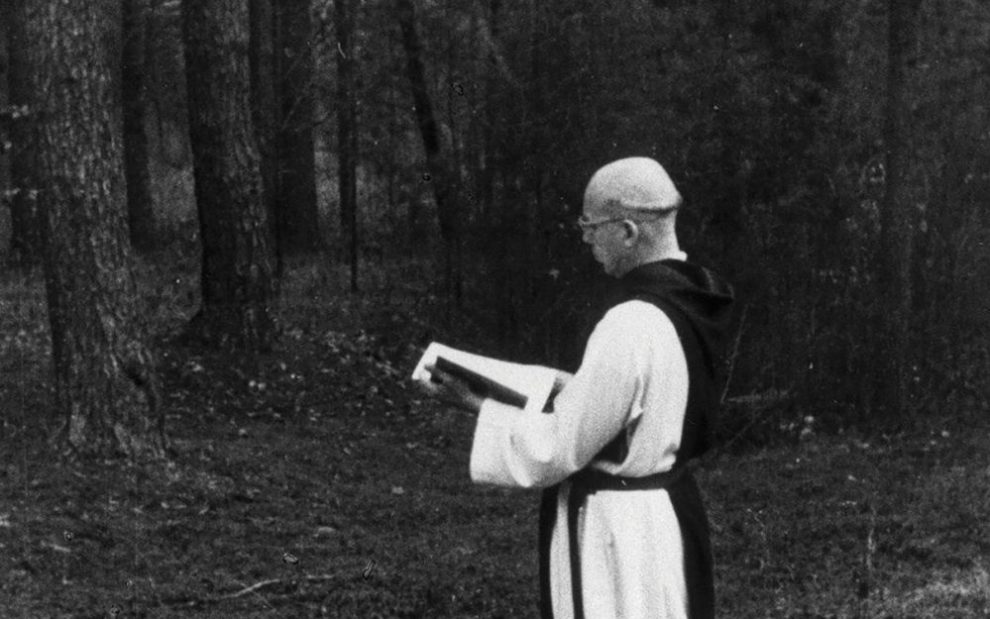

Merton was born in a white body. Yet he was not confined by it. He acknowledged racial injustice and spoke boldly against it, moving beyond his privilege to embrace people in Black bodies and their arguments against white supremacy. He stood with African Americans in questioning the “certitudes of their time.” In doing so, he literally put his well-being and life on the line—in the United States and in the Catholic Church. How had I not known this important aspect of who Merton was? Who celebrates this Merton?

I was born in a Black female body on what was once land of the Muscogee, 10 miles from an Army base named in honor of a secessionist. The time was just before the 1960s, the decade remembered for its questioning of certitudes about class, gender, and race. My birth was preceded by the end of World War II; the Montgomery bus boycott; Brown v. the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas; the murder of Emmett Till; and the beginning of the Vietnam War. Each of these resulted from and led to more questioning.

In a region with few Catholics, three generations of my family entered the Catholic Church during my early childhood. This did not happen in a vacuum or resolve the challenges of our society. The first decade of my life also included the Freedom Riders, the election of the first Catholic president of the United States, the hateful rhetoric of segregationists, and St. Pope John XXIII convening the Second Vatican Council. My early years witnessed the first man journeying into space, Bloody Sunday, the march from Selma to Montgomery, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the bombing of Birmingham’s 16th Street Baptist Church, and Martin Luther King Jr. receiving the Nobel Peace Prize. Many, but not all, mourned the murders of James Chaney, Addie Mae Collins, Medgar Evers, Andrew Goodman, John F. Kennedy, Robert F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King Jr., Viola Liuzzo, Carol Denise McNair, Carole Robertson, Michael Schwerner, Cynthia Wesley, Malcolm X, and countless others.

Yes, like today, they were heavy days. The experiences named are only some of those that defined the environment I shared with Merton. Restricted by differing labels of race and gender, would our shared Catholic faith allow us to transcend differences and connect in a grace-filled manner?

Merton is known and celebrated as a contemplative, but this term in isolation whitewashes the memory of the man Merton was. From my experience and from the writing of Franciscan Father Richard Rohr, I have learned to see contemplation as more than an end in and of itself. The practice of contemplation allows space for the divine. Whether God moves in this space or merely sits with me, I try to be present. For me, that is what contemplation is—quieting my body and mind to allow space for God. Contemplation does not remove me from the pain and struggles of life but allows me to see what I must do. Contemplation and action nurture each other. Merton understood this.

While Merton resided at the Abbey of Our Lady of Gethsemani in Kentucky for decades, neither his intellectual curiosity nor his worldview was confined to its walls. He challenged the status quo by speaking to the injustices of our time. His respect for dialogue compelled him to encounter people through correspondence, sharing with and listening to people with experiences different from his own. In 1963, he wrote “Letters to a White Liberal,” which became the foundation for his book Seeds of Destruction (Farrar, Straus and Giroux).

As an African American Catholic, I have memories of a few priests and women religious in the marches of the civil rights movement. However, in general I continue to be disappointed by the tendency of the church to ignore or deny the significance of racial injustice today. So I was surprised by Merton’s message to white Christians on their culpability in the sin of racism. I wondered if this book was a one-time effort or if he had dared to say more on the topic. My questioning of Merton’s authenticity was a natural response to a Christian in a white body speaking on the proverbial elephant in the room.

Decades after the civil rights movement of the 1960s, most people in white bodies are quick to claim they are not racists. Unfortunately, this merely means they do not want to be affiliated with blatant acts of racism. They are usually unaware of how racism, anti-Blackness, and white supremacy are woven into the fibers of our nation and our church. It is easier for them to assume that this is my problem as a woman in a Black body. They don’t recognize that their silence makes them complicit.

Merton first captured my attention with what would become one of my favorite prayers: “My Lord God, I have no idea where I am going, I do not see the road ahead of me. I cannot know for certain where it will end. Nor do I really know myself.” These words spoke to me and illumined the contents of my heart. As I approached a significant birthday with inner angst, Merton affirmed my desire to serve God.

Enamored by Merton’s use of language, I approached his book The Seven Storey Mountain (Harcourt Brace) with anticipation. While many have been inspired by this autobiographical classic, it never resonated with me, even after multiple attempts. Puzzled, I accepted my disappointment with gratitude for the cherished prayer by the man who died months after my 10th birthday.

Years later, my curiosity led me back to Merton and his work, particularly to a passionate letter he wrote to the acclaimed writer James Baldwin about his book The Fire Next Time (Dial Press). Merton affirmed the writer’s perspective on the systemic injustices of racism and the justified anger of African Americans. Disappointed by the whitewashing of American Christianity and its impotence against white supremacy, Baldwin chose to speak outside a religious context. However, Merton believed the struggle for dignity and freedom was essentially religious.

The Abbey of Gethsemani is just over 300 miles from the 16th Street Baptist Church. The drive can be made in five hours. Carol Denise McNair was 11 when she and three other girls were murdered there on a Sunday morning, when the Ku Klux Klan, white men who vehemently opposed the civil rights movement, bombed the church. One year after the tragedy, Merton drafted a heartfelt letter to Chris McNair, the father of Carol Denise, expressing his sympathy and confidence that God had welcomed Carol Denise into God’s embrace. He wrote of the task to continue the work for justice and equality. Almost 50 years later, the energy of the words remains poignant.

Once, in downtown Louisville, Kentucky, at the intersection of Fourth and Walnut, Merton had a significant epiphany, an experience of profound awareness of our connection to each other, transcending constructed boundaries. This is the Merton I sought and found. My brothers and sisters in white bodies can use him as a model in moving beyond fear and privilege into humility and courage. We are blessed to witness how one man questioned the certitudes of his time.

This article also appears in the October 2022 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 87, No. 10, pages 15-16). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Flickr/Jim Forest (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Add comment