“Stand still and allow the strange, deadly restlessness of our tragic age to fall away like the worn-out dusty cloak that it is.”

—Catherine de Hueck Doherty

For me, the distinct pull toward Russian spirituality was not something that developed over time. Rather it descended all at once like a warm cloak on a cold night.

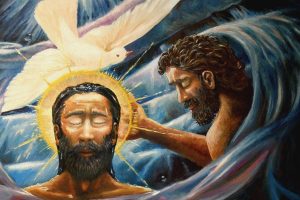

I was standing in a city art gallery. The show was of Russian iconography, those brightly painted, solemn-faced portrayals of Jesus and Mary and saints such as Basil and Gregory. The display shone in candlelight, and a recording of Eastern Orthodox chants haunted the air. Probably in deference to the beauty of art and music, most in the crowd refrained from speaking as they filed slowly past the paintings.

In that gallery I was overcome by a huge peace. I read on one of the display panels that icons are more than paintings or holy pictures; they are believed to capture the spiritual essence—the transfigured likeness—of the figure being portrayed. However it happened, I was shaken by a power that seemed to draw me into mystery and stillness.

“You must read Catherine de Hueck Doherty,” a friend said later as I described my close encounter with a Russian mystical experience.

And so I did.

Today the cause for the canonization of Doherty, a former Russian baroness, is under consideration by the church. But when I first discovered her work and thought in the late 1970s, she was still considered a bit troublesome.

Doherty was a peer of Dorothy Day, and the two women were similar in their passion for social justice and in their establishment of Catholic lay communities committed to the poor. Both were authors and lecturers on God and the gospel, and both were outspoken critics of the church and society on matters of poverty, economic justice, and race.

Further, Catherine Doherty was a significant pioneer in the introduction of Eastern spirituality to the West. She loved to describe the immense tenderness and mercy of God at a time when the divine was usually viewed as something to be feared. And she spoke passionately of the “desert experience” of silence and solitude where God’s mercy can be experienced. “True silence is a key to the immense and flaming heart of God,” she said.

Born in 1896 to a wealthy family in Russia, Doherty was 15 when she married a cousin, Baron Boris de Hueck. With her husband and young son, she fled the country during the Russian Revolution and arrived penniless in Canada in 1920. To support her family, she worked as a maid, sales clerk, laundress, and eventually, with a lecture bureau.

She was continually haunted by the words of Christ: “Sell all that you have and give to the poor, and come follow me.” So after her marriage fell apart and with her son’s education provided for, Doherty began giving away her possessions.

In the early 1930s she lived with the poor in an impoverished section of Toronto and founded Friendship House there as a Catholic interracial apostolate and soup kitchen. She went on to establish Harlem Friendship House in New York City, where one volunteer in 1942 was none other than Thomas Merton, who became a lifelong friend and champion.

She married well-known American crime reporter Eddie Doherty, and together the couple founded Madonna House in rural Combermere, Ontario. The apostolate still operates as a community of Catholic laypeople and priests who embrace lives of prayer and simplicity and make yearlong, renewable promises of poverty, chastity, and obedience.

I was fascinated by Doherty’s blend of contemplation and action—and by her concept of poustinia (the Russian word for “desert”). In her books Doherty explains that Russian homes often featured a small room or closet where family members might pray and meditate. But poustinia can be any solitary place where one meets God. A commute in the car to work, a moment at the kitchen table—these are “little deserts, the tiny pools of silence” that God offers as gifts to encounter him dwelling within.

For Doherty, however, the quest for stillness cannot serve as a selfish pursuit. Inner quiet breaks forth in charity that overflows without counting the cost, she said. Availability to others becomes delightful and easy.

“God has created us to be icons of Christ,” she wrote. “We must follow Christ in the rhythm of his own life, the rhythm of solitude and action. What is needed today is to retire to solitude and silence, to hear the voice of God, to glorify and pray to him, and then to return to the secular world.”

With Doherty as a role model, I began volunteering for a church-sponsored inner-city program for teenagers in New York. Eventually I was hired there as a counselor and also worked occasionally at a local soup kitchen. My poustinia—a small altar in my fifth-floor walk-up—and a lively local church community fueled the work, which was often difficult.

And at some point, there in my fairly humble city surroundings, I began to write and to paint. Even today, manila folders in my home are crammed with the life stories of the neighborhood people whose lives intersected mine in those days. And on watercolor paper are the still, tender faces of Christ—the Christ, Catherine Doherty pointed out, who looks with such mercy on the world.

Selected resources:

- Tumbleweed: A Biography of Catherine Doherty by Eddie Doherty (Madonna House Publications, 1988).

- Poustinia: Encountering God in Silence, Solitude, and Prayer by Catherine De Hueck Doherty (Madonna House Publications, 2000).

- madonnahouse.org

This article also appears in the June 2010 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 75, No. 6, pages 47-48). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Madonna House Archives

Add comment