College student Maria Dominguez juggled a lot during her junior year as a political science major at Dominican University in River Forest, Illinois. In addition to a full course load and a part-time job at the campus library, she still found time to spend nine hours a week volunteering with preschool children as part of Ministry en lo Cotidiano (MLC), or “Ministry in the Everyday,” a program run by the university’s campus ministry that encourages leadership development and faith formation.

Dominguez, who is Mexican, transferred to Dominican last year after earning her associate degree from a community college and working for a while. She joined MLC to serve her local community and earn a stipend to help cover her expenses.

“To me that was extremely appealing—to go to school and be a student while also doing something to help, to give back a little,” she says. “Being in school full time and learning about all these things can be very stressful. Being with these kids for six hours a week was relaxing, even though they were always very loud and energetic.”

As part of MLC, Dominguez attended a weekly discussion group where students talked about their volunteer experiences and learned about Latin American and Latino/a theology. Dominguez says she has struggled to know where she fits in as a Mexican living in the United States. She has also felt estranged from the church, like it has nothing to say to her and is not relevant to her interests. Being able to learn about Latino/a theology and, in particular, the mujerista (Latina feminist) theologians, was eye-opening and inspiring.

“It was really refreshing and a new take on something I had grown up with my whole life,” Dominguez says. “Growing up, I wasn’t really taught about Latine theologians, so it was interesting to hear that there were Latinas who influenced the field. The church is still really closed off to women, and it feels empowering to know there are Latinas who are studying this and influencing this. It’s very important.”

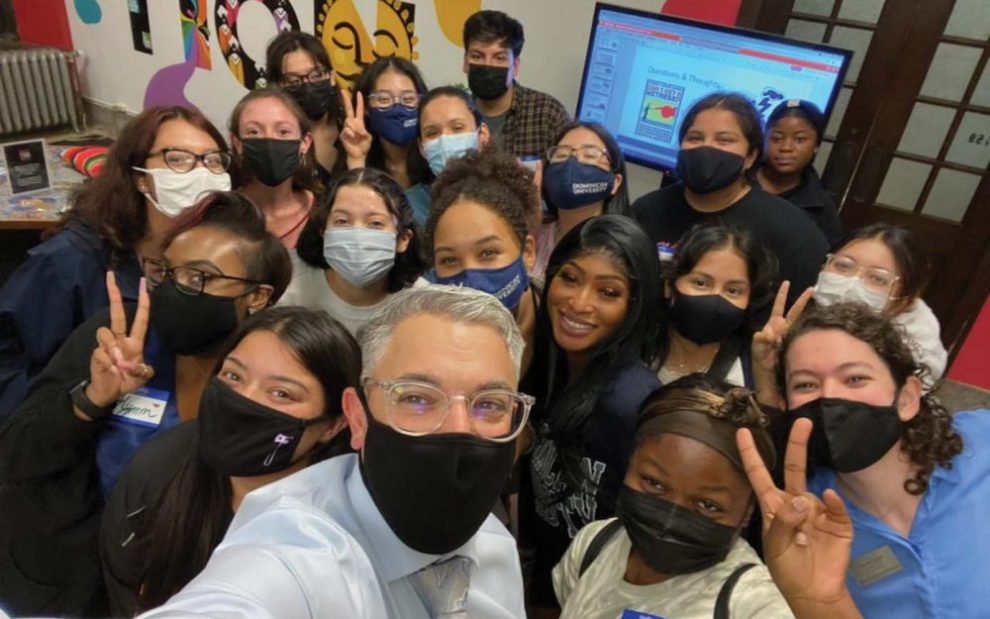

Helping students like Dominguez connect with their identities and faith traditions is a key goal of Dominican’s approach to campus ministry, which is centered around culturally responsive ministries that engage with students based on their individual cultures, faith traditions, and life experiences. In addition to MLC, the university is also home to programs such as the Beloved Community, a student leadership and faith formation group founded in African American faith communities, and Faith in the Vaccine, a ministry in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

John DeCostanza, assistant vice president of university ministry at Dominican, believes the shift to culturally responsive ministry has led to a greater sense of belonging and investment from participating students.

“That came from understanding the ways in which their lived experiences and their families and communities were really centered,” he says.

The ministry also helps meet an important gap within the church. Recent numbers from the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops estimate that 59 percent of Catholics in the United States are Latino/a. For Catholics under age 18, that number rises slightly to 60 percent. While the demographics of Catholic young people have become more Latino/a, many campus ministry programs have been slow to adjust their pastoral approach.

Salvatorian Father Raúl Gómez-Ruiz is the president-rector of Sacred Heart Seminary and School of Theology in Franklin, Wisconsin. He spent more than 15 years working as the seminary’s director of Hispanic studies. When it comes to ministering to Latino/a Catholics today, he believes there’s a disconnect between what ministers are doing and who they are doing it for. In many parishes, he says, Latino/a ministry programs are oriented toward Spanish-speaking recent immigrants who have come from a “more traditional life.”

“The problem with that is that second, third, fourth generations get lost a little bit,” he says. “College ministries need to take this into account: Which generations are we dealing with? What are their aspirations?”

While certain experiences are universal to all young people, Gómez-Ruiz says it is important to consider Latino/a students’ specific relationships to their culture and the challenges and discrimination they may face. Many Latino/a students, like Dominguez, have significant commitments outside of their studies such as part-time jobs or family obligations. Not all Latino/a young people speak Spanish, but they might still appreciate the incorporation of cultural elements into their faith practices.

“It’s not like you have to completely shift gears to minister to them, but you have to ask questions about what things they are carrying unconsciously with their backgrounds,” Gómez-Ruiz says. “How can you uncover what is there to help them navigate what they are living through?”

When Latino/a communities aren’t recognized in ministry or their perspectives aren’t incorporated, there is a danger that they will write off the church or look elsewhere to get their spiritual needs met. The result, Gómez-Ruiz says, is a “loss of people who can contribute to the church’s dynamism and development.”

College ministries need to take this into account: Which generations are we dealing with? What are their aspirations?Father Raúl Gómez-Ruiz

Amirah Orozco, co-coordinator of MLC, agrees about the importance of Latino/a young people to the church’s future. She thinks it’s crucial for ministers to start recognizing and celebrating their unique gifts.

“Latine people are both the present and the future of the U.S. Catholic Church,” Orozco says. “To do anything in ministry that is not attuned to that reality is to do bad ministry or lazy ministry. I think there’s a historical requirement of the church that we now begin to acknowledge those cultural gifts our students bring instead of thinking of them as something to shy away from.”

Embrace the complexity

So what is standing in the way of effectively ministering to Latino/a young people? Carmen Nanko-Fernández, director of the Hispanic theology and ministry program at Catholic Theological Union in Chicago, believes that many well-intentioned Latino/a ministries fail because they don’t understand to whom they are ministering.

“There’s this whole mentality that if you do an event in Spanish and throw a serape on it you have things covered,” she says. “That’s really an issue, and it shows itself in campus ministry as well as other ministries.”

Her advice for campus ministers is to never make assumptions, including about what languages students speak, what traditions they celebrate, or even what they would like to be called: Hispanic, Latino, or gender-neutral terms such as Latine or Latinx.

“It’s important to understand the complexity of who’s in front of you,” Nanko-Fernández says.

It is also vital, she notes, to have an understanding of Latino/a theological thought and the richness that lies within. One big difference between Latino/a Catholicism and many American traditions, she notes, is the way religion intersects with everyday life. In Latino/a cultures, she says, “the U.S. impulse to separate sacred and secular doesn’t really exist. . . . [Latino/a Catholics] believe the sacred accompanies the daily so the little things matter. That stuff of daily life is also a legitimate source for theologizing.”

This can work to campus ministry’s advantage, she says, because universities are “places where daily life and pastoral life come together in big ways.” But a danger can be treading into the world of Latino/a traditions without understanding their deeper theological underpinning.

“Without the background, you might see a Day of the Dead altar and think, ‘Isn’t that great and touching,’ as opposed to understanding that there’s a whole world of meaning to that and that the meanings aren’t always the same for everyone,” Nanko-Fernández says. “Campus ministry needs to understand these practices as theological moments instead of cultural showpieces.”

Some challenges in this regard, she notes, are a lack of Latino/a professors and theologians as well as a lack of available training in Latino/a theology to educate campus ministers. Nanko-Fernández also cites the frequent conflation between Latin American and Latino/a theology: The former refers to theologies coming out of Latin America while the latter arises from the Latino/a lived experience in the United States. “Most of the young Latino/as in the United States are born and raised and educated in the United States,” she says. “And while some campus ministers might know Gustavo Gutierrez or Leonardo Boff, because schools study Latin American theologians, they do not know or study our Latino/a theologies—and that is what needs to inform campus ministry.”

It’s important to understand the complexity of who’s in front of you.Carmen Nanko-Fernández

According to the Association of Theological Schools, Latino/as accounted for only 7 percent of the students enrolled as theology students in the fall of 2017. Among the faculty of those institutions, Latino/as represented less than 4.5 percent of the full-time professors. These numbers point to a lack of trained ministers who have received religious formation in Latino/a cultural traditions from Latino/a voices.

“In a university setting where you can expect to have this kind of lively discussion and education taking place, oftentimes that doesn’t happen,” Nanko-Fernández says.

Those lively discussions about cultural identity and faith traditions are an important aspect of MLC, according to Orozco and her co-coordinator, Krista Chinchilla-Patzke. While the service component allows students to work within Latino/a communities, the weekly reflections let students discuss their volunteer experiences while tying in their bicultural identities, spiritual ideas, and goals.

This year’s program, which included 17 students, was centered on the themes of synodality and the communion of saints. By studying Latin American theologians such as Gustavo Gutiérrez and several mujerista theologians, the students learned where their cultural identities fit on the spectrum of theological thought and that voices like theirs matter.

“Part of the reason why [the students] are so attracted to this theology is because they see, ‘Oh, this was my experience too and [these theologians] wrote about it,’ ” Chinchilla-Patzke says. “As they’ve been grappling with a lot of these authors, there have been light bulb moments when they realize that their experiences are holy and God is in them.”

Both Orozco and Chinchilla-Patzke are passionate about doing ministry that reflects the Latino/a perspective because of their past experiences in campus ministry. Orozco, who grew up on the border of Mexico and Texas, was involved in immersion service programs during her undergraduate years at Boston College. But as a Mexican American, she had a hard time reconciling the Catholicism practiced on campus with the faith traditions she had grown up with. Similarly, Chinchilla-Patzke, who was born in Guatemala and moved to the United States at age 7, remembers experiencing “pockets of representation” for her Latina identity while in undergraduate campus ministry, but she never found a ministry to help her better synthesize and understand her bicultural identity.

For campus ministers to be successful in serving Latino/a students, Orozco believes they must be willing to hear student perspectives and invite them into a “cominister relationship.”

“Although professional ministers have theological training that students do not, it does not mean students have no experience that is valuable,” she says. “To accompany anyone is to acknowledge their gifts and experiences as worthy of theological insight.”

A great example of this, she remembers, was when Dominican hosted a Day of the Dead celebration in 2021. The theme for the night was students’ hopes and losses related to the COVID-19 pandemic, and it was intended to be a moment of grief where the community could pull together. The time leading up to the event was a long process, involving intensive planning and creative work to design and build the ofrenda (offering). In the end, hundreds of students, faculty, and staff from the university participated in or attended the event.

“The ofrenda was a powerful moment in which our students accompanied one another and were accompanied by us in grief,” Orozco says. “It was one of these moments you recognize that when ministry is pulled from the experiences of our students, the students will show up. They will make themselves available and take ownership over the process.”

“Our students are ecclesial agents of which we are forming and accompanying,” she adds. “But they are also leading the church alongside us.”

Meet young people where they are

Claretian Missionary Father Eddie De León is the director of intercultural outreach at Catholic Theological Union. Earlier in his career, he spent 17 years in campus ministry, including a four-year chaplaincy at Yale University, where he created an intercultural student outreach program.

De León’s goal was to accompany students of color and create spaces where they could feel like they belonged, no matter their beliefs. To do this, he sought out places on campus where students of color gathered so he could learn about their interests and help build a space that would reflect their challenges and interests.

By listening to the interests of students, De León was able to plan events that drew large crowds, including a procession for the feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe that featured mariachi music, tamales, and presentations from well-respected Latino/a theologians. On another occasion, De León hosted an event on campus with Dominican American author Junot Díaz.

“I looked at that as pre-evangelization because people who had never been to campus ministry before lined up to come here,” De León says. “They saw that the community was cool, relevant, and at the pulse of student life. It wasn’t a religious event, but in a way it tapped on all those religious components of spirituality, community, and the common good.”

At the end of his four years at Yale, the program hosted its first ever Latino/a graduation party for 200 students and their families.

“People would say to me, ‘I’m not Catholic, but I feel very much a part of this community,’ ” De León says.

The key to successful ministry, he says, is to always listen to what the community needs and to take what Pope Francis calls a “loving gaze.”

“Every community is different, so essentially I always have to be with them and figure out what it is that I keep hearing, what their hopes, their anxieties, and their dreams are,” De León says. “It’s really about assessing the people and seeing what we can do for them. And then if we can’t do it, looking to find out if maybe there’s someone who can.”

That kind of loving gaze is at the heart of Iskali, a Chicago-based organization that accompanies and empowers Latino/a youth on their faith journeys. Founder Vicente Del Real started the ministry after noticing a lack of targeted ministries for U.S.-born Latino/as.

“When you look at the statistics, it’s clear that the future of the church is brown. The future of the church is Latino,” Del Real says. “If we don’t invest in young Latinos today, we won’t have Latinos in the church in the future, and their children won’t be there.”

Our students are ecclesial agents of which we are forming and accompanying. But they are also leading the church alongside us.Amirah Orozco

Marcos Martinez leads Iskali’s campus ministry efforts, connecting Latino/a community college students with scholarships and professional mentors. Fifteen students are currently enrolled in the campus ministry program, including many first-generation college students with questions about college logistics, including where and what to study and how to find internships.

Martinez hopes that, by getting involved with Iskali, students will feel empowered to meet their goals while growing in their faith. While the Latino/a culture is often rooted deeply in Catholicism, many young people lack an understanding of how the faith fits into their life. He also thinks it’s important for Latino/a young people to feel proud of their culture and who they are.

“We deserve to be celebrated because the music, the food, the traditions—they are all very beautiful,” he says. “We shouldn’t try to suppress that to make other people comfortable. We should help them see the beauty in our traditions so they can be celebrated.”

Both Del Real and Martinez believe Latino/a voices are needed to lead any kind of ministry efforts for Latino/a youth. To help make this possible, they work with young people to build their confidence and leadership abilities.

Del Real draws inspiration from the story of Our Lady of Guadalupe who appeared to Juan Diego in 1531, a time when Indigenous people were not yet recognized by the church as humans. After Mary asked him to share his story with the bishop, Juan Diego hid from her because he was afraid his voice wouldn’t be heard due to his identity and lack of influence. Seeking him out, Mary told him, “It must be you.”

“That’s what we tell our young people here. We know we don’t have answers, but as we embark on the journey of accompanying others, it must be us,” Del Real says. “We need young Latinos to accompany other young Latinos, embracing their culture, embracing their wounds, and embracing their traditions.”

Del Real knows that many Latino/a young people live in an in-between where they “feel too white for their Mexican friends or too Mexican for their white friends.”

“What we’ve created in Iskali is a place where they don’t have to pretend to be somebody else,” he says. “They can just be themselves.”

This article also appears in the August 2022 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 87, No. 8, pages 26-30). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Courtesy of John DeCostanza

Add comment