With confusion and anticipation, I watched Daniel make his way to the large crucifix that rested on risers for veneration. He moved on his knees toward the image of Christ. If all I knew of him was the sincerity of his crawling, I would have thought he was in the final stretches of pilgrimage to pay homage at the Santuario de Guadalupe. As Daniel drew near, he placed his forehead upon the sacred icon with the reverence of the Filipino tradition of touching one’s forehead to the back side of a priest’s hand. Yet Daniel is neither Mexican nor Filipino Catholic. He isn’t Catholic at all. He is a white, nondenominational, evangelical Christian.

I met Daniel when we both attended the “Pilgrimage of Trust” facilitated by brothers from the Taizé community. What we shared in our time of prayer was the very mission of the white-robed men who spoke to us through thick French accents. Taizé is not a religious order nor denomination. It is not even a strictly defined approach to prayer or spirituality. It is an intentional, ecumenical community of Christians from diverse backgrounds seeking to inspire unity, trust, and hope in the world.

As a musician, I had previously encountered Taizé prayer. I had assumed it was simply a style of music: soothing, peaceful, repetitive chants carefully composed to be sung in numerous languages at once. I was unaware of the profound history and spiritual roots of these ethereal melodies.

Although I was already a professed religious brother preparing for priesthood at the time, my ignorance was in a way reflective of the tradition itself.

What is Taizé

Taizé was founded in France amid the profound divisions and discord of the Second World War by Roger Schütz—known to many as Brother Roger—to foster reconciliation and peace. From risky acts of mercy like welcoming refugees to the community amid the Nazi-supported Vichy regime to the evolution of inclusive, candlelit contemplative prayer services, Taizé has become a visible beacon of the authenticity of the gospel. Schütz was adamant that this movement was not to become self-interested but rather directed toward inspiring authentic Christianity in existing communities. He did not want to spread the practice of Taizé but its mission of unity.

It is not surprising then that Taizé is at once famous and invisible. More than 100,000 pilgrims flood into the small French village and monastery every year, all coming from different backgrounds but sharing an aspiration to heal a broken world. During one Holy Week, more pilgrims came than could fit in the church. They had just finished a stained glass wall at the back of the nave, but they took it down to accommodate a tent for the crowds. Their mission was not the building—it was unity.

There is no way to be a part of Taizé in a formalized way, as in a monastic community. Although many come to encounter Taizé each year with the community, they disperse with the goal of seeking reconciliation and unity in their own communities with their own traditions. I attended the “Pilgrimage of Trust” in Chicago with a group of young adults from the Archdiocese of Santa Fe in New Mexico. Upon returning home, they desperately wanted to create a Taizé ministry. At first they desired to recreate the candlelit services and bright orange banners reminiscent of the flames of the Holy Spirit. Instead they began, as many have around the world, a ministry of prayer in the spirit of Taizé.

Taizé has become a visible beacon of the authenticity of the gospel.

Advertisement

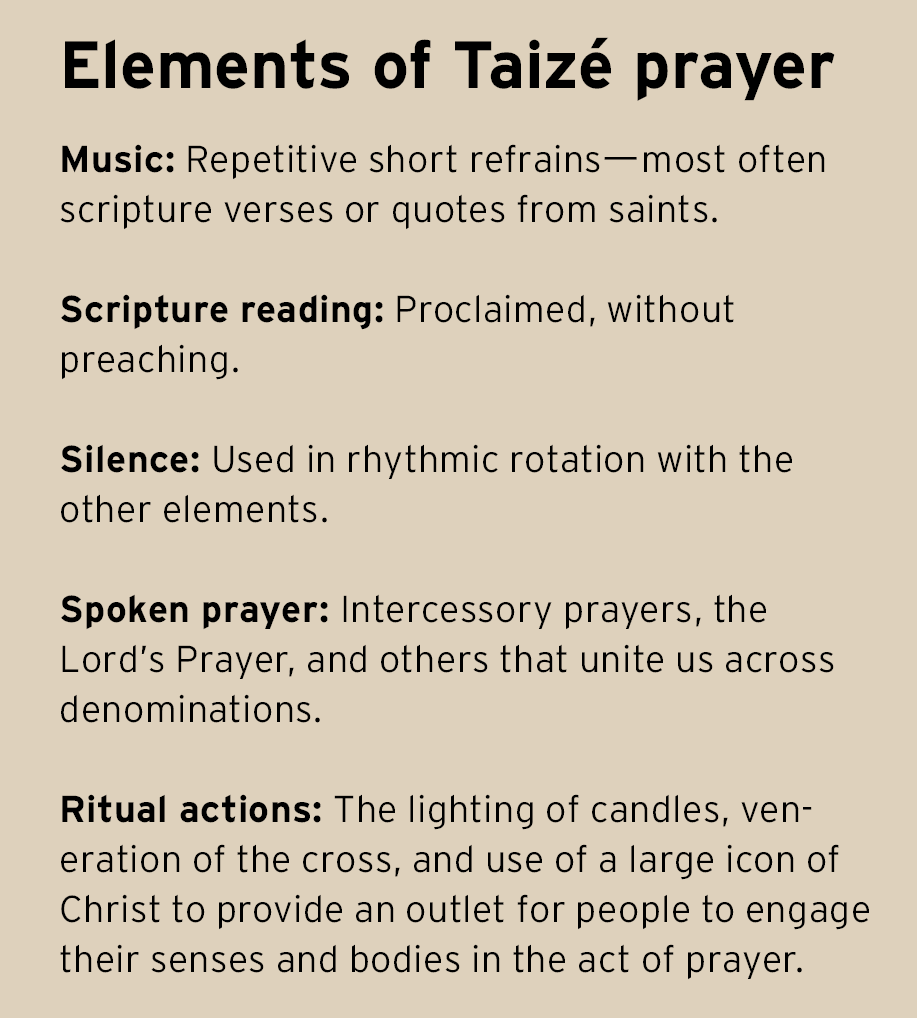

The practice of Taizé worship

Taizé uses certain central elements: music, scripture, silence, prayer, and ritual actions. There is no wrong way to combine these elements. I have attended services that incorporate praying over individuals for healing or others that take the spirit of Taizé as the backdrop for eucharistic adoration. Whatever the final design of a Taizé liturgy, the central goal is to create a space in which any person can come to engage in prayer at their own level and pace.

Repetitive singing and silence, as well as an emphasis on reading scripture, allow participants to find a sense of unity with one another without having to cross into divisive or controversial arenas. The rituals of candle lighting and cross veneration allow those with devotional spirits to enact that part of themselves but let others who do not feel moved to do so simply sit in wafting tones of chanting and soothing moments of silence. A well-designed liturgy in this spirit is one that is open to active engagement on the part of participants but allows individuals to discern what that means for them. This is reflected in the compositional style of the music—equally accessible as multilingual and harmonized expressions with rich instrumental descants and as simple a cappella monophonic chants.

Nine years ago Christians from diverse backgrounds began gathering monthly in our small monastery chapel perched on a dry, sandy escarpment southwest of Albuquerque, New Mexico. “Taizé in the Desert” has continued, evolved, grown, and changed. Yet its core mission to create an intimate space for people to find healing and seek unity continues to be the same, which deepens our monastery’s own mission of peace, reconciliation, and unity. Each month Catholic youth groups, evangelical young adults, and veteran members of mainline Protestant congregations quietly gather to sing words of scripture and the saints, to light flames of hope, and to lay down their burdens together at the foot of the cross. As different as our faith journeys may be, in those moments we witness a truth that is also real—what unites us in Christ is deeper than whatever could divide us.

My friendship with Daniel transcended denomination and doctrine. We knew there was something deeper that drew us together. I asked him what it was like to engage in practices that to me seemed profoundly “Catholic” with use of sacramentals, rituals, chant, and silence. He told me that the neutral context of worship in the spirit of Taizé allowed him to feel safe doing what might seem like “devotional things.” He didn’t have to set aside his own tradition or profess union with a new one to enter into these experiences. He could do so alongside others who found similar meaning.

My friendship with Daniel transcended denomination and doctrine.

Prayer in the spirit of Taizé presents a unique opportunity. Within Catholicism we see a number of young adults steeping themselves in what are perceived as more historical practices of the church. It seems that greater numbers of young people are seeing no value to their heritage faith and joining the ranks of the Nones. Although there is much ritual within a Taizé service, at its best it is unbound. It is an organic evolution in the midst of the service. It does not require instruction but simply modeling. Community members engage as they see fit and as the Spirit moves them.

The spirit of Taizé does not seek to replace other forms of worship. It is not there to create devotees of Taizé. It is lifted up to inspire individuals and communities to be authentically themselves alongside others who may seem very different and yet can lift their hearts to God just the same.

This article also appears in the July 2021 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 86, No. 7, pages 45-46). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: YouTube/Somos de la Vid

Add comment