A quiet life of faithfulness—in many ways—is the kind of life I hope to lead. I don’t desire to make a show of my faith; Jesus himself tells us not to.

I have always believed that a quiet life of faith is the best form of evangelism. When we truly live out our lives as Catholics doing what Catholics should do, that will speak more words than any of us could ever write on the subject.

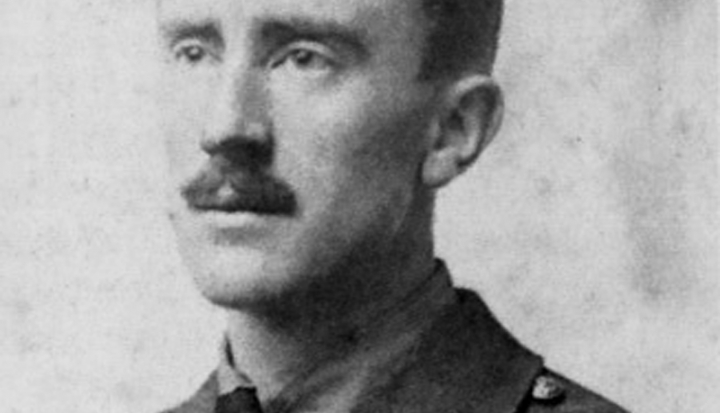

J.R.R. Tolkien, a man so intimately related to words and language and even fame and notoriety, lived such a quiet life of faithfulness.

When I was in college my goal was to be, and I quote, “the next C.S. Lewis.” At the time what I claimed to mean was that I desired to write the kinds of things he did, theology and fiction. What lay under that was the desire to be famous as he was. Most of my life since then has been a reminder that this lot is not for me.

Humphrey Carpenter in his biography on Tolkien describes a usual day in Tolkien’s life in Oxford. Carpenter wends in various domestic touches to give us a sense of being present in Tolkien’s home.

What I’ve always loved about the description Carpenter gives is the simple nature of Tolkien’s Mass attendance. Carpenter describes it as taking place on a saint’s day so Tolkien must wake early, wake his boys, dress—putting off shaving until later—and then ride on bicycles with his two boys to St. Aloysius Catholic Church three-quarters of a mile away. Tolkien often traveled to daily Mass in this way.

Of course, Tolkien’s life was not a perfect one. His wife, Edith, in particular struggled with becoming Catholic—a necessary condition for their marriage at the time—and seems not to have come often with him to Mass. Still, one can see in Tolkien a desire to be frequently and yet quietly with Christ. After all, despite being an author of some renown, few of his books have direct mention of religion in general and certainly not Catholicism in particular.

There are still many people who do not realize Tolkien was Catholic. They know him only as the author of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. But this is because Tolkien seeks to work on us in more subtle ways.

Tolkien in a letter dated December 2, 1953 writes:

“The Lord of the Rings is of course a fundamentally religious and Catholic work; unconsciously so at first, but consciously in the revisions. That is why I have not put in, or have cut out, practically all references to anything like ‘religion,’ to cults or practices, in the imaginary world. For the religious element is absorbed into the story and the symbolism. However that is very clumsily put, and sounds more self-important than I feel. For as a matter of fact, I have consciously planned very little and should chiefly be grateful for having been brought up (since I was eight) in a Faith that has nourished me and taught me all the little that I know . . . ” (Letter 142).

Here we see Tolkien reflecting back on The Lord of the Rings, seeing it as an inherently Catholic work precisely because it was written by a man who sees the world from, who understands reality with, a Catholic imagination.

In his essay, “On Fairy-Stories,” written after The Hobbit but before The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien argues that part of what fairy stories or fantasy can do for us is give us better vision, help us to see things in a new light. He does not go so far as to say “seeing things as they are,” but he does suggest that we might see things “as we are or were meant to see them.”

This is part of the mission of Tolkien’s fiction. The Lord of the Rings is not an allegory—Tolkien was not a great fan—though he did employ it from time to time, but the novel is full of symbolism and can help us see.

Tolkien’s understated Catholicism in his fictional work—the presence of Eru Ilúvatar in The Silmarillion notwithstanding—has been of personal importance for me.

Tolkien’s words have been the bread and butter of my imagination since I was a baby hearing my mother read The Hobbit to me in the crib. His way of training us to see the world through a sacramental lens, a Catholic imagination, has worked on me. I see things differently now precisely because I grew up reading Tolkien (and C. S. Lewis, G. K. Chesterton, and George MacDonald).

What is more, Tolkien is one of the principal people who aided me in becoming Catholic. And while the subtlety of his almost imaginative apologetics laid the foundation, it was in his letters, especially to his children, that showed me how deeply rooted Tolkien’s Catholicism was.

Since college, I have begun to learn the importance of a lack of self-importance. I no longer desire to be the next anything. I don’t want to be C.S. Lewis or Tolkien or Chesterton or anyone. I want to be me, the person Christ has called me to be. And I am content now to live in relative obscurity.

But I can only do this if I can live out that quiet life of faithfulness that Tolkien exhibited. For some time I have believed that we must get much smaller, we must pay just a little less attention to the global stage, a little less to the national, and much more to the city, the family, the self. But not in some selfish or self-centered way, but rather in that quiet life of faithfulness, where I can truly live out my faith in my family, in my parish, in my city.

Maybe that steady faithfulness will ripple out. Maybe it won’t. I haven’t been called to the ripples, I’ve been called to the center, to the drop of the rock. To that I must be faithful.

In a letter to his son Michael, Tolkien discusses marriage and the nature of relationships between men and women. This leads him into a discussion of his time in World War I. Tolkien was newly affianced, and now he was headed to the Somme. He writes beautifully about how he found the light after the horrors of war:

“Out of the darkness of my life, so much frustrated, I put before you the one great thing to love on earth: the Blessed Sacrament . . . . There you will find romance, glory, honour, fidelity, and the true way of all your loves upon earth, and more than that: Death: by the divine paradox, that which ends life, and demands the surrender of all, and yet by the taste (or foretaste) of which alone can what you seek in your earthly relationships (love, faithfulness, joy) be maintained, or take on that complexion of reality, of eternal endurance, which every man’s heart desires” (Letter 43).

For Tolkien the Eucharist was the end, the telos, of marriage and of all things on earth. Everything—trees, grass, man, hobbit, elf—is bound up in the presence of Christ on earth. This is how Tolkien in his quiet life of faithfulness saw things. It is how he has taught and is teaching me to see things.

Yes, he had and has international fame and acclaim, but this is a product of his faithfulness, of his unrelenting desire for Christ, a desire that did not manifest itself in a series of theological books but works of fantasy so that we might be changed from the inside out. And I have been so changed. A quiet life of faithfulness—that is what I long for.

This article also appears in the February 2019 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 84, No. 2, pages 45–46).

Add comment