I was well into my adult years before I knew the church had a day set aside for the Feast of the Holy Innocents, a commemoration of King Herod’s murder of all young male children in Bethlehem. I happened to go to daily Mass on December 28 maybe 15 years ago, 10 years after the loss of my own child. There I was reminded of King Herod’s massacre, intended to eliminate the threat posed to his crown by the infant Jesus.

An Advent baby, my son Michael was born on the Feast of St. Nicholas (December 6) and succumbed to birth defects 11 days later, a week before Christmas and 11 days before the Feast of the Holy Innocents. It’s a season filled with memories, and this feast day only brought Michael closer to my mind.

Of the gospel writers, only Matthew tells the story of Herod’s orders. The resulting flight of the Holy Family to Egypt conflicts with Luke’s timeline, the only other evangelist to recount Jesus’ infancy. The Roman Jewish historian Josephus, despite writing about many Herodian atrocities, does not mention this one—although it could be argued that, compared to other killings by Herod, the relatively small number of deaths might not have risen to Josephus’ attention. The number of murdered children is also disputed. Early Christian reckonings ranged widely, from 14,000 to 144,000, despite the fact that today’s estimates put ancient Bethlehem’s total population at around 1,000.

Biblical scholars suggest that Matthew’s purpose was to present Jesus as fulfilling Old Testament prophecies and to liken him to Moses, who was born during—and escaped from—Pharaoh’s massacre of young Israelites. While historians find little corroboration for Matthew’s account of the massacre, they acknowledge that it’s consistent with Herod’s behavior. After all, he executed his own sons, and some suggest those murders might be another inspiration for the massacre story.

If the massacre’s historical accuracy is dubious, its symbolism is poignant. Beyond the sheer tragedy, it portrays worldly resistance to the divine will on a metaphysical level. In a more mundane sense, it’s a powerful and paranoid king attempting to eliminate a threat at all costs. Patron saints against ambition, the Innocents—fictional or not—are perhaps the ultimate tragic victims, paying the price extracted by a tyrant who would die soon himself, on behalf of a newborn who wouldn’t come into his own until 30 years hence.

Compared to the intimacy of my wife’s and my loss, the capitalized term “Innocent” has an unfortunate effect of distancing the children from their humanity and their earthly families. Often considered the first martyrs for Jesus (although martyrs usually make a conscious faith choice that leads to their death), their martyrdom almost glorifies away the tragedy. They are more than human, an ideal of innocence. In another way, they are somewhat less than human. Always grouped together, they lose individuality. But they had names, they had genders, they had personalities. And they had parents. The parents don’t factor much into the tradition—at best they appear as distraught, helpless victims in medieval art—and they don’t seem to be patrons for anything.

In the time since my son’s death, I’ve come across a handful of patron saints of the loss of children. As I’ve found is common with patronages, the saints’ connection to the purpose isn’t always clear. Some of these patrons don’t seem to have lost children, or they simply outlived their adult children. Some of them are not particularly sympathetic—royals, such as St. Clotilde (d. 545), whose power- and wealth-hungry children died or killed each other in the pursuit of more power and wealth—and resemble Herod more than his victims.

For others, their grief is often overwhelmed in their biographies by the hagiographic glow of their exemplary faith—as ideal and hard to aspire to as the Innocents’ innocence. More than one woman, widowed and having lost children, entered a convent—St. Dorothy of Montau (d. 1394), St. Hedwig (d. 1243), and St. Joaquina Vedruna de Mas (d. 1854), to name a few. The latter two wealthy women also put their estates to work for the church and the poor. Fathers became saints, too. St. Isidore the Farmer (d. 1130) lost his only child and thereafter became so devout his coworkers complained about his spiritual distraction. The worldly Blessed Luchesius (d. 1260) lost all his children and, realizing he had forfeited the best of his life to pursue wealth and power, then devoted the rest of his life to the sick, poor, and imprisoned. This path of grieving parents dedicating themselves to relieving the suffering of others is shared by relatively recent saints on this continent, including St. Elizabeth Ann Seton (d. 1821), Blessed Mother Mary Alphonsa (born Rose Hawthorne, daughter of the author Nathaniel Hawthorne, d. 1926), and St. Marguerite d’Youville of Canada (d. 1771).

Even though there are some inspiring patrons, I wasn’t seeking patron saints when we lost Michael. I was too lost myself to look. Nor did we go for counseling or support groups. That doesn’t mean we needed no one. They just found us before we knew to look.

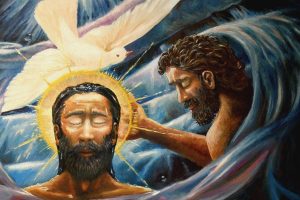

We were lucky to be quickly surrounded by people who loved us and cared for us and our child. They came to be with us in the hospital, at home, and at the memorial service and burial. Our lives stopped, of course, but so did those of so many others. My brother accompanied me to the other hospital Michael was sent to on the day of his birth. My wife’s parents and siblings watched our 17-month-old son. My parents flew across the country. Cousins and nephews and other relatives were just present. And there was a truly joyful—a truly spirited—gathering of much of our two families in the neonatal intensive care unit during Michael’s baptism, where the presence of all those people was augmented, so the lump in my throat told me, by another holy presence.

The murder of the Holy Innocents is a brutal and tragic story—for the children, of course, but for the parents, too. One can barely imagine the aftermath. Distraught and confused by the inexplicable slaughter—unexplained and unexplainable. Left now, only with the lifeless. How could they go on?

Fortunately, as happened after Michael’s birth, many family and friends would have descended on Bethlehem to be with those grieving parents to offer prayer, comfort, and support. It makes me recall a photo of my wife from the baptism. Despite the situation and gowned for the ICU, she has a proud, beatific smile, possible only because of the intercession of those people around us. The answer to prayers we didn’t know we’d said, they were our patron saints.

This article also appears in the December 2016 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 81, No. 12, pages 31–32).

Image: Flickr cc via Brian Wolfe

Add comment