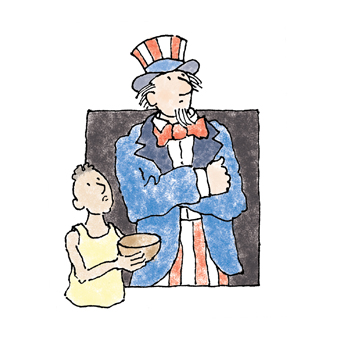

With billions in aid on the chopping block, who is looking out for the world’s poor?

The first hard numbers emerging out of the famine in Somalia are staggering: Between May and August, U.S. aid officials estimate that more than 29,000 children under the age of 5 died in southern Somalia alone. The famine threatens 12 million in the region; the U.N. reports that 640,000 Somali children are acutely malnourished, suggesting the death toll among children is certain to rise.

The relief effort promises to be difficult, challenged by geography and the region’s poor-to-nonexistent infrastructure, and complicated, too, by the presence of al-Shabaab Muslim extremists. Aid from the United States has begun to reach those most hungry, but sadly the rush of aid in early August arrived too late to save the lives of thousands of children. But how much higher would that death toll be if emergency aid from the U.S. weren’t coming at all?

What if, in an effort to reduce the federal deficit at home, Americans turned their backs on the suffering and the starving around the world? It seems incomprehensible that the world’s richest nation might abandon the pivotal role it has played in humanitarian relief, but that is exactly what some fear might happen as the United States puts together a plan to cut $2.4 to $3 trillion from the federal budget over the next 10 years.

Hidden within the $50 billion State Department budget is most of the money for relief and development work that the United States conducts. When you whittle away all the State Department’s “international” aid that actually fronts for military spending, you end up with something in the vicinity of $30 billion of actual funding for relief and development.

Former U.N. Ambassador and member of Congress Tony Hall, now an advocate for the world’s hungry, worries aid programs will be especially vulnerable as deficit reduction decisions are made. International aid is not protected by natural constituencies in the United States, he says. Politicians are not likely to suffer recriminations at the ballot box if they cut off funding. Lives are at stake, says Hall.

Since billions in aid to Israel, Egypt, and “partners” in “overseas contingency operations”—what we used to call the “war on terror”—in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan will apparently remain sacrosanct in the upcoming negotiations, budget hawks will likely target that $30 billion or so in development and relief aid. Considering the trillions that have to be cut, it is worth calculating whether the loss of U.S. influence and prestige—and lives—is really worth the tiny contribution foreign aid cuts could make toward deficit reduction.

Speaking on behalf of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, Albany, New York’s Bishop Howard Hubbard, chairman of the bishops’ Committee on International Justice and Peace, and Catholic Relief Services President Ken Hackett rejected a recent proposal to cut humanitarian funding floated by House Republicans in July. That plan, they wrote in a letter to Congress, “makes morally unacceptable, even deadly, cuts to poverty-focused humanitarian and development assistance . . . that will undermine integral human development, poverty reduction initiatives, and stability in the world’s poorest countries and communities.”

Hard decisions will have to be made as the nation attempts to restore its fiscal health. But when the choice is between feeding the world’s hungry and funneling more subsidies to U.S. farmers, will we make the right call?

By supporting the U.N.’s Millennium Development Goals in 2000, the United States joined an alliance of the world’s wealthiest nations in an unprecedented effort to reduce measures of poverty and deprivation worldwide by half by 2015. That date is fast approaching, and there’s still a long way to go.

The 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution requires that the validity of U.S. public debt “shall not be questioned.” The nation is properly concerned with shoring up the credibility of that commitment. What will it take for us to feel the same responsibility to live up to the commitment we have likewise made to the world’s poor?

They have no lobbying firms to argue their case; they have no politicians, bankers, or bureaucrats in their pockets. They only have us.

This article appeared in the October 2011 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 76, No. 10, page 39).

Image: Tom Wright

Add comment