November 10th marks the 50th anniversary of the release of Patti Smith’s landmark debut album, Horses. A blend of poetry and back-to-basics rock and roll the album came at a time of budding music movement, providing a connection to the past while breaking away from it. Known today as punk rock, this new musical landscape took shape in small New York clubs, such as CBGBs and Max’s Kansas City, with Smith as one of its central figures and Horses as one of its seminal statements.

Both artsy and visceral, Horses embodies a unique point of view, a style Smith herself dubbed “three chords merged with the power of the word.” Themes of birth and death, grief and loss, rebellion and liberation, transcendence and the sea of possibilities can be found throughout the album’s eight tracks.

While many listeners would not classify the album as Christian or overtly religious (more likely the opposite), the themes are those explored by anyone who strives and searches for truth. “Somebody once pointed out to me that I was a religious poet. I didn’t even realize it,” Smith said in 1973. Horses is art that is both intellectually engaging and emotionally moving. It’s the type of art that invites you to look inside yourself for truth and find something bigger at play in the world around you, outside of your own ego.

The transcendence of Horses set the stage for a religious exploration that can be seen throughout Smith’s career and life. Consisting of many unexpected twists and turns, Smith’s spiritual journey ended up in a surprising place. From an often-contemptuous relationship with Christianity, Smith’s rebellion against Jesus morphed into a loving embrace.

Like many people before and after her, Smith’s youthful defiance included rebellion against the religion in which she was raised, in her case, Jehovah’s Witnesses. A glance at her parents shows the seeds of both her religiosity and rebellion. “My father taught us not to be a pawn in God’s game. He used to blaspheme and swear against God, putting Him down. I got that side of me from him. The religious part is from my mother, who is a complete religious fanatic,” Smith told Interview magazine in 1973.

Smith turned away from organized religion as a teenager, making writers and musicians her saints: figures like William Blake, Bob Dylan, Lou Reed, and French poet Arthur Rimbaud. Rimbaud’s surrealist poetry and irreverent bohemian lifestyle were central influences on Smith when, in 1967, she moved to New York City with aspirations to become a poet.

The beginnings of Horses stem from the collaboration between Smith and guitarist Lenny Kaye. The two met in 1971, when Smith asked Kaye to back up her poetry readings with some improvisational guitar work. After they teamed up with piano player Richard Sohl, the trio, with the help of Television front man Tom Verlaine, released their first single, a cover of Hendrix’s “Hey Joe,” backed with “Piss Factory,” an original song Smith wrote about her time working in a factory.

Thanks to this single and the group’s live performance, record executive Clive Davis sought them out and signed them to his new label, Arista Records. The Patti Smith Group entered Electric Lady Studio on September 2, 1975, and with ex-Velvet Underground member John Cale as producer, spent the next five weeks creating their legendary debut album. (The album’s release date coincidentally coincided with the anniversary of the death of Patti’s beloved Rimbaud.)

The songs on Horses cover a lot of ground, both lyrically and musically, and the group expanded further with the addition of drummer Jay Dee Daugherty and second guitarist Ivan Kral, who also played bass. While three-chord rock is the glue that holds the album together, the songs explore many different musical ideas, from garage rock (“Gloria,” “Free Money”) to reggae (“Redondo Beach”) to free jazz (“Birdland”). The interplay of the instrumentalist seamlessly transitions between structured song and improvisation. This intuitive musical language was thanks in part to the players’ live-performance style.

Lyrically, Smith explores a range of emotions and concepts. “Birdland” is a sprawling sci-fi epic that addresses the grief of losing a loved one. Inspired by the 1973 memoir of psychoanalyst William Reich, A Book of Dreams, the lyrics describe a boy who imagines his father is not dead but has become an alien piloting a spacecraft. “Kimberly,” named after Smith’s younger sister, speaks of the awe one experiences at the birth of a sibling. “Break It Up” shows the struggle to break through to a more transcendent self, inspired by a dream Smith had after visiting Jim Morrison’s grave. The album’s finale, “Elegie,” is a melancholy piano ballad about “remembering them all, past, present, and future, those we had lost, were losing, and would ultimately lose.”

The centerpiece of the album is the nine-and-a-half-minute “Land.” Broken into three parts, the saga exemplifies the seamless fusion of poetry, improvisation, and three-chord garage rock, telling a story via long and surreal poetics. The tale’s protagonist has a vision of being surrounded by horses, horses, horses. This blends into a cover of “Land of a Thousand Dances,” connecting the vision of horses with the 1962 dance hit’s opening line, “Do you know how to pony like Bony Maroney?” The song comes to a head as Smith combines several interspliced poetic vocal takes, showcasing the group’s unique fusion of rock and roll’s roots with symbolist verse.

While critically acclaimed, Horses was not without controversy, particularly to the Christian listener. The album opens with “Gloria,” mixing poetry with the 1960s classic of the same name (originally by Van Morrison-led band Them). The song begins with the proclamation, “Jesus died for somebody’s sins, but not mine.” The line came from a poem Smith wrote in the early 1970s entitled “Oath.” Though not included in her first few books of poetry, “Oath” was a staple at her early live-poetry readings.

“I had written the line some years before as a declaration of existence, as a vow to take responsibility for my own actions,” Smith wrote in her 2010 award-winning memoir, Just Kids. Years earlier, she told Terry Gross during her 1996 appearance on NPR’s Fresh Air: “People constantly came up to me and said ‘you’re an atheist, you don’t believe in Jesus,’ and I said, ‘obviously I believe in him,’” then adding, “I didn’t want him taking responsibility for my wrongdoings or my youthful explorations. I wanted to be free.”

Only a little over a year after Horses came out, an event took place that would forever change the trajectory of Smith’s spiritual journey. Following the release of the Patti Smith Group’s second album, Radio Ethiopia, they opened a concert for Bob Seger in Tampa, Florida on January 23, 1977. Smith had developed a custom of whirling around while performing. During “Ain’t It Strange,” a song Smith stated was written as a challenge to God, Smith started to twirl but tripped and fell off the stage, breaking her neck.

Patti interpreted her fall and injury, particularly that it happened during that song, as a sign. Her near-death experience and subsequent recovery period gave Smith time to reassess things, particularly spiritual matters. “I’m learning to accept a more New Testament kind of communication. So as part of that acceptance, I have to re-evaluate exactly who Christ was.”

Following this reassessment of her relationship with God, Smith didn’t perform the song “Gloria” for some time. On this, drummer Jay Dee Daugherty said, “I think Patti changed and came to grips with her own spirituality and some sort of a spiritual system. I think she didn’t feel that way anymore.”

In Florence, Italy, more than two years after her fall, Smith once again performed “Gloria,” only this time a little differently. She sang the infamous opening line but with a slight change: “Jesus died for somebody’s sins, why not mine?”

Smith continued to use religious imagery throughout her career. Her third album, the first after her fall, aptly titled Easter, even featured a spoken-word reference to Psalm 23 in the song “Privilege (Set Me Free).” On her next album, 1979’s Wave, she dedicated the title track to Pope John Paul I, whose short papacy coincided with the album’s recording. The album even features a picture of the pope on its inside art.

While Smith has never embraced the Catholic faith, its impact on her work is especially clear with the advent of social media. Her Instagram page, which she personally curates, often features religious imagery, commemorates saints’ feast days, and acknowledges Christmas and Easter as Christ’s birth and resurrection. In 2013, Smith met Pope Francis after one of his general audiences in St. Peter’s Square and was even asked to play at the 2014 Christmas concert for the Vatican.

Like much of Smith’s career, this invitation came with some controversy, particularly due to that inflammatory first line on Horses. To this, Smith retorted: “Anyone who would confine me to a line from 20 years ago is a fool!” In 2021, Smith was invited back to the Vatican to perform for a second time.

Smith wanted to be Arthur Rimbaud, Keith Richards, and Joan of Arc rolled into one. She wanted to find truth through poetry and song, to take the old and transform it into an elevated new. With this lifelong commitment to examination and development, Patti Smith moved from a relationship that constantly challenged God to something deeper.

“I reassessed Jesus Christ,” she told the Philadelphia City Paper in 1995, “and realized that he gave us the simplest and greatest ideas: to love one another, making God accessible to all men, and giving people a sense of community, that they would never be alone.” So maybe, just maybe, one of those horses that appeared in Smith’s surreal musical vision happened to have “a rider who was called faithful and true” (Revelation 19:11).

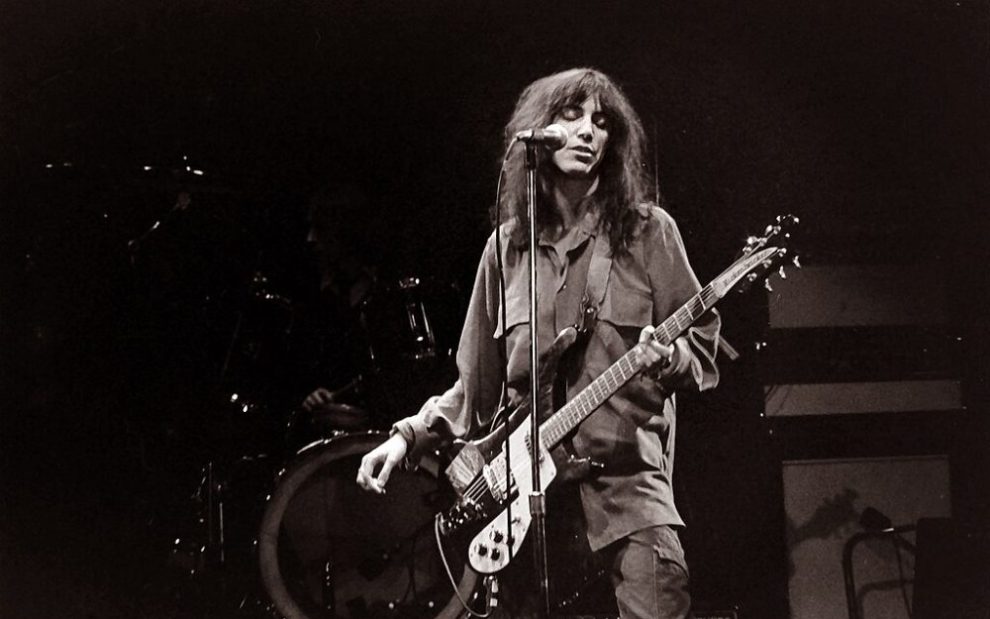

Image: Wikimedia Commons/Bodow (CC BY-SA 4.0), Patti Smith performs at Rockplast in Germany, April 1979

Add comment