Across the United States, Claretian Missionaries fostered Spanish-speaking parishes for Latino migrants in working-class neighborhoods. Claretians put these parishes on the map by hiring architects, planting the seeds of parish societies, and creating opportunities for lay leadership. In her new book, Pioneers of Latino Ministry historian Deborah Kanter reveals how Claretians successfully mediated diocesan preferences for centralization and Americanization and Mexican and Puerto Rican Catholics’ desire to nurture the culture of home. Nowhere better represents this approach than industrial Perth Amboy, New Jersey, where Claretians shepherded a Latino Catholic community despite the city’s industrial decline. Since 1947, Latino Catholics cycled through several reused buildings, waiting decades to realize their dream of building a modern church of their own.

When Claretian priests dedicated the new Our Lady of Fatima Church on September 19, 1971, the city of Perth Amboy was suffering from deindustrialization and population loss. As jobs left the city, older Euro-American congregations struggled to maintain their parishes. From coast to coast, and especially in inner cities, new church construction had ground to a halt. But the Claretians recognized the great need and the potential of Perth Amboy’s growing Latino population. Presenting their vision to the diocese, the Claretians showed how a new parish could reverse these trends and become a center of spiritual and community life.

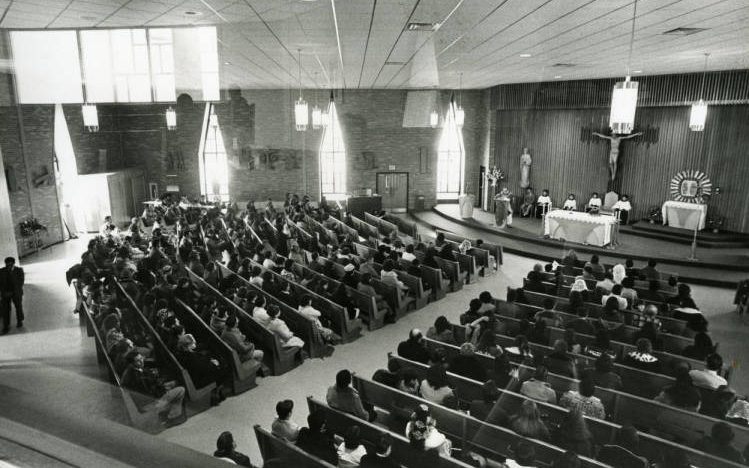

After a procession led by the bishop, over 700 people poured into the new sanctuary for a bilingual liturgy. Former Claretian pastors Fathers Thomas Matin and Walter Mischke returned for the dedication and first Mass, alongside Fr. Raymond Bianchi CMF. Holy Name men, Apostolate of Prayer women, families with roots in many parts of Latin America filled the pews that fanned out in a near semi-circle. They marveled at the sanctuary’s clean lines and uncluttered views. The space embodied the Vatican II ideal that “the church building is the house of people”; like a modern house, “roomy, bright, pleasant, restful, open”, allowing people to “see each other, hear each other rejoice in each other’s presence.” The up-to-date church, built to enable the laity’s active participation in the changing Catholic church, probably took some getting used to. Yet after twenty years in temporary worship spaces, católicos rejoiced in their modern, spacious home in Perth Amboy.

Four Claretian priests and six Mexican sisters “totally committed to the catechetical and social work” supported the parish’s vibrant spiritual life. The sisters, with thirteen lay teachers, ran the CCD program that served 800 children each week. Fr. Luis Turon CMF supported new parishes societies to increase lay involvement in the spirit of Vatican II. At Fatima, the largest parish societies included the Holy Name, the Dominican Hijos de Altagracia, the Apostolado de Oración, and the Hijas de María. Other active societies included Young Christian Students, Niños de la Cruzada Eucarístico, and the Christian Family Movement. Hundreds of people had taken part in cursillos. The free-standing church social center had a large gym that hosted plays, concerts, retreats, and banquets. The social center was—and remains–a busy place. The Claretian stamp on downtown continues: the old, makeshift parish center from the 1960s was attractively rehabbed as the Claret Center in 2019.

Since the arrival of Fr. James Tort CMF in the late 1940s, the Claretians advocated on behalf of the once small population of Puerto Ricans, who had often been painted in a negative light by the local press and police. The Claretians created spaces in which the community could grow, offer mutual aid, and meet on Sundays and throughout the week. The parish’s modern, large buildings in downtown were a highly visible sign of católicos’ arrival and respectability in Perth Amboy.

The Claretians rose to the challenge of establishing parishes in dioceses throughout the country. They visited families in boxcars and scattered apartments, listened to their needs, and then initiated regular worship—often in provisional spaces, such as a repurposed barracks or a two-story house. The Claretians convinced diocesan authorities that Latino communities deserved proper, dignified churches in unlikely spaces such as a barrio with unpaved streets, under the shadow of steelyards, or on a bottling plant brownfield. When these new churches opened their doors, the Claretians met the spiritual needs of arrivals from Mexico and the Spanish Caribbean, and their children growing up in the United States. The parishes of Immaculate Heart of Mary in San Antonio, Our Lady of Guadalupe in Chicago, and Our Lady of Fatima in Perth Amboy stand today as the fruits of the Claretians’ commitment and as vital Catholic sites of refuge.

A Q&A with Deborah Kanter

How did you end up working on this project?

My previous book, Chicago Católico: Making Catholic Parishes Mexican (University of Illinois Press), explored the Claretian Missionaries’ groundbreaking work in Chicago. No one, I realized, had written a book on the Claretians in the United States. So, I took the story national, from Texas to Illinois, California to New Jersey, and beyond. The project allowed me to explore the evolving world of Catholic America in a way that centers Latinos.

What was the most challenging aspect of working on this book?

The Claretians worked in more than 100 places in the United States, of which 30 had a longtime Claretian presence. I had to narrow down which places and people to concentrate on. The quality and variety of sources often tipped my decisions. Ideally a combination of intriguing photos, well-written letters or diaries, and secular as well as religious sources helped me assemble compelling historical scenes.

In the course of your research, did you discover anything that surprised you?

The international composition of Claretian priests and brothers today, with many men from Latin America, Asia, and Africa! Pioneers of Latino Ministry (New York University Press) largely focused on the transition from an entirely Spanish membership before 1930 to an American majority and leadership circa 1960. But today the province stands at another turning point. In the next decade or so, no national group will dominate. The USA-Canada province embodies “mission in reverse.”

What was your favorite story or detail that you learned, in the course of your research?

The history of the U.S. Claretian missions in Guatemala c. 1967–2001 astounds me. I discovered a box of hundreds of ID cards for women and men who trained as catechists and health workers, many of whom were Indigenous. The cards were a bit of a mystery until I learned about the 18 lay martyrs from eastern Guatemala that the Vatican now recognizes as Servants of God. Pioneers tells the stories of several of these laypeople who worked directly with the Claretians.

What can readers learn from this book, about the church’s role in the history of immigration in the United States?

Catholic churches have been essential to immigrants’ homemaking. Bishops throughout the country invited the Claretian Missionaries to begin ministry for the growing Spanish-speaking population. For immigrants, these parishes became sites of refuge and spaces of Catholic Americanization. These churches connect immigrant parents and their U.S.-reared children. With the assault on immigrants today, more than ever, Catholic dioceses and parishes need to include and support immigrants and their families in meaningful ways.

What can this book teach us about the pastoral and mission-focused nature of the church?

Pope Francis urged in Fratelli Tutti (On Fraternity and Social Friendship), “For all the progress we have made, we are still ‘illiterate’ when it comes to accompanying, caring for and supporting the most frail and vulnerable members of our developed societies. We have become accustomed to looking the other way, passing by, ignoring situations until they affect us directly.” Given the preponderance of Latino laypeople in the United States, many clergy members remain “illiterate” in accompanying and recognizing their needs. Clergy and lay leaders can learn from Claretians’ pioneering Latino ministry in generations past. The Claretians’ accompaniment of Hispanic Catholics stands out in over a century of work in this country.

Why is it important to keep alive the history of the Claretians’ Latino ministry?

Today, Latinos make up about half of U.S. Catholics. The Claretians were intimately linked to the Latino people they served and continue to serve. They carried out missions and sustained parishes in marginalized communities whose histories deserve telling.

Image: Eucharist at Our Lady of Fatima Church in Perth Amboy, N.J. Courtesy of Claretian Missionary Archives USA-Canada.

Add comment