On June 17, 2025, Holy Family Parish, a Catholic Church in Gaza, was struck by an Israeli shell that killed three people and injured several others. This church, where over 600 people—including Palestinian Christians, Muslims, young children, and disabled individuals—continue to shelter in amidst death and destruction, is the same church that Pope Francis called nightly until his death this past April. One month after the attack, Father Gabriel Romanelli, the church’s pastor, told Vatican News that “We feel almost entirely alone in this area.”

In crisis times, the most vulnerable in our society suffer the worst outcomes. We see this in public health crises, in times of war, and during natural disasters, among other scenarios. The poorest communities and the most marginalized groups are left for dead. Sometimes I see the use of wartime vocabulary to explain away these losses, specifically with the term “collateral damage.” This phrase gained widespread use during the Vietnam War and has proliferated since then.

In military settings, “collateral damage” is a phrase used to denote the unintended deaths and destruction resulting from wartime operations. Typically, this destruction is an unfortunate, incidental outcome to an intended operation, like civilians killed by an airstrike targeted at opposing forces.

Who are we willing to sacrifice?

So, though the Holy Family Parish community contains our siblings in faith, we’re likely to count them—perhaps quietly or privately—as acceptable collateral damage in the grand scheme of a “complex geopolitical conflict” (or something to that effect). Of course, though this view may present itself as rational or even-keeled, what underlies it is a chilling logic with pernicious impacts.

The logic of “collateral damage”—whereby we determine an acceptable human expenditure for some political, social, economic, or other outcome—is not confined to the battlefield. It seeps into ordinary life as well.

Throughout human history, political pundits have found it expedient to create a category of people who could be acceptably expendable for various outcomes. In the last half-decade, we’ve seen a global pandemic, at least two international wars, countless environmental disasters and social injustices unfold, and other events that have created alienating conditions for our society’s most vulnerable members. These events have also created categories of “othering” which make it easier for the general public to abandon “out groups.”

We don’t have to look far back to see this alienation at work. Take, for instance, the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID disproportionately impacted Black and brown community members across the United States. A startling 2022 study published in the Journal of Social Science & Medicine found that white Americans surveyed in fall 2020 were less likely to follow safety precautions after learning about these disproportionate impacts.

And when former U.S. President Joe Biden ended the public health emergency stage of the pandemic in 2023, vulnerable community members fell by the wayside. In April 2024, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that 18 million Americans suffered from long COVID, a debilitating post-viral condition resulting from being infected with COVID-19. A 2024 study by Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery (RECOVER) found that long COVID surpassed asthma as the most common chronic condition impacting children in the United States, with an estimated 5.8 million children affected.

A nihilistic “logic”

Since 2020, political leaders have disarmed community members with reminders that COVID would “only hurt X group”—and so created a category of people with whom we created distance, and so became comfortable with discarding. With COVID, chronically ill, immunocompromised, and medically vulnerable community members became acceptable collateral damage, as their needs “inconveniently” disrupted desires to “go back to normal.”

The logic of “collateral damage” has persisted into other areas of ordinary life. We see this logic at work when citizens praise careless and incoherent budget cuts across the board, from academic grants to life-saving social welfare programs, for the ideal of reducing the deficit. Though that ideal was not realized, real individuals and communities paid a hefty cost—but to many, these groups are acceptable collateral damage. This logic reveals itself in the blasé responses from politicians like Iowa State Senator Jodi Ernst, whose reply to constituents raising concerns about those who may die from Medicaid cuts was “Well, we are all going to die.”

If we’re looking for this logic made manifest, we have fertile ground from which to choose. We can, for example, look to the pundits who pose for photo ops at brutal immigration detention camps, cheerfully release merchandise for said camps, and take to social media to joke about alligators devouring detainees.

We can also look to the victims of senseless environmental disasters—from schoolchildren in Texas’ Camp Mystic to communities across North Carolina and West Virginia still reeling from Hurricane Helene’s destruction—who are mourned but tacitly accepted as collateral damage by politicians whose hostilities and ignorance towards climate innovation and environmental infrastructure reign supreme.

And we can return to the “battlefield” to see the logic of collateral damage justify unimaginable suffering and carnage. This logic animates current geopolitical conflicts, where military advancements—some U.S.-funded—crush civilians thousands of miles away for the sake of broader aims and outcomes.

For example, I think of this logic when I recall the story of Hind Rajab, a 6-year-old Palestinian girl who was fleeing with her family from Gaza City when an Israeli tank fired 355 rounds into their vehicle, killing them. I also think of Muhammad Bhar, a 24-year-old Palestinian man with Down syndrome who was mauled by an IDF military dog and died. And I think of Nahida and Samar Anton, two Christian women who were shot and killed by an Israeli sniper in December 2023 while walking to the Sister’s Convent inside the grounds of Holy Family Parish.

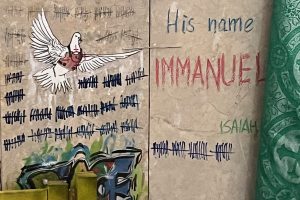

The way of Christ

In a world that embraces this logic at any cost—be it drowned communities, obliterated infants, and detained families—it’s easy to become desensitized. Yet the Christian tradition can provide deliverance from this logic. In these times, I return again and again to the parable of the Good Samaritan, where Christ provides a reorienting lens in his response to the question, “Who is my neighbor?” This question has been a guiding light in my journey as a Christian, broadening the boundaries of my care and concern towards unfamiliar faces and places near and far. It’s helped me temper prejudices and, as Jesus illustrates with the Samaritan man, learn how to extend compassion beyond my comfort zone.

As news of domestic and international injustices punctuates my daily life, I approach this question anew. Nowadays, I find myself asking an amended version of this question: “Which of my neighbors is collateral damage?” This question produces answers that painfully reveal the ways that I—and we—have numbed ourselves to our neighbors’ dehumanization and what we have lost in that process.

As Christ enjoins us, the ignored and discarded peoples of our world ought to count among our neighbors and so be treated in kind (and preferentially so, as the church reveals in Catholic social doctrine). As our faith teaches, in a world that rewards tuning out the suffering of vulnerable groups worldwide, we have an opportunity and responsibility to ascertain a “countercultural” role: leaning in and expressing our concern through solidarity and support.

This work begins with prayer—for a conversion of hearts, and for realizing our responsibility to those abandoned. Gaza’s Father Romanelli concurs, noting that “Food, medicine, and fuel are as essential to us as prayer itself. Without prayer, ours and yours, we would not have made it this far. We are counting on you.”

Image: Unsplash/Mohammed Ibrahim

Add comment