Mmusong is a small but vibrant Catholic community of about 700 high in the mountains of South Africa. On Sundays the simple church building is full, but most of the time not for Mass, only for a service of the Word.

Mass is something rare in Mmusong. The priest of the distant parish center serves nine communities, and he is able to celebrate Mass in Mmusong only once a month.

Mmusong, however, is by no means desolate. There is no Sunday when the community feels lost. It has several teams of trained leaders who prepare themselves during the week to conduct a lively and meaningful Sunday service. The people will thus hear a well-prepared sermon every week, even when there is no priest.

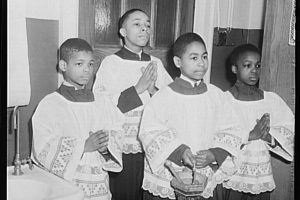

There are teams of others who conduct funerals wearing liturgical garb, signifying that what these leaders do is the liturgy of the church, not a private prayer. Similarly there are trained catechism teachers, youth leaders, and leaders of gospel-sharing groups. The priest of this parish has helped each of the nine communities in his care to become a “self-ministering” community.

As the bishop of the diocese, I would visit Mmusong once a year, listening to the community and solemnly blessing its leaders. Each time I went home with the same painful question in my heart: “Why can I give only a blessing to those leaders? Why can I not ordain some of them? When will the day come when I can ordain the proven leaders of our communities?”

I know that if the church continues to admit only celibate, university-trained candidates to ordination, there will be no hope of ever overcoming the scarcity of sacraments. I equally know that the early church indeed did ordain local leaders who were married, had received brief local training, were chosen by the local community, and had proven their worthiness over some time.

I am not alone. There are hundreds of bishops who feel that renewing this ancient tradition is the only solution to the shortage of priests. There are hundreds of other bishops, however, who feel that ordaining local leaders would be dangerous. They fear it might solve one problem by creating bigger ones.

The ordination of married candidates would unavoidably raise questions: Why could some priests be married while others had to remain celibate? Why did some have to go through university education while others could be trained on weekends? Are we not creating two classes of priests? Others fear a kind of clericalization of the laity, whereby one pious person could forever dominate a congregation.

It is indeed a complicated question whether the shortage of priests could be solved by ordaining proven local leaders. The question will not become easier if we keep silent about it. If discussed by many, it will become more apparent that certain proposals will not work while others will.

“The Lord’s Day and the Lord’s Supper belong together” must remain our key principle. In about half of all Catholic communities in the world, these two things-the Lord’s day and the Lord’s Supper, which intrinsically belong together-have in fact become separated.

Thousands of communities meet on Sunday not for the Eucharist but for a service of the Word. We cannot allow this situation to continue. If the faithful and the priests become used to this wound in our faith life, they will give up looking for solutions. We vehemently oppose other distortions of our faith; therefore we must reject this one as well.

There are signs of hope. The communities that have no resident priest have proven that they usually possess all charisms that would be needed for the ordination of local leaders. Without the shortage of priests, most of these charisms would have remained undetected. Now that they are apparent, it is time to follow the example of the early church (Acts 14:23). Paul writes to Titus that he “should appoint elders in every town” (1:5).

The last few decades have also been a chance to learn a few practical lessons. One of them is that we should not place key responsibilities on only one person in the community. If we consider ordaining proven local leaders in the communities, then we should ordain not just one but always a team of them.

Another lesson we have learned is to choose the right term for such a team of ordained local leaders. They would be a distinct kind of priest and should be called by a distinct name, such as the original term used in the New Testament: elder. We should not speak of “auxiliary priests” or of “part-time priests” or of “community priests.” Although the latter term is beautiful in itself, it would tempt people to compare those ordained elders with the traditional, seminary-educated priests, and such comparisons would be harmful.

If proven local leaders are ordained as elders, they should not be regarded as a primitive imitation of the present priests or a second class of priests. They should not even try to be similar to the existing priests. The principle should be “as distinct as possible,” not “as similar as possible,” so as to avoid comparisons. Just as lay leaders are highly respected today, the ordained elders of tomorrow would be highly respected-provided they are clearly distinct.

This means that we would have two different forms of priesthood. Both receive the same sacrament of Holy Orders. Theologically speaking both are priests, but in daily life we would always use two different terms: priests and elders.

The two kinds would exercise two different roles. The elders would lead the community and administer the sacraments in their own community, while the priests would be the spiritual guides of elders in several self-ministering communities. The priests would thus serve the whole diocese, while the elders would serve only the community where they were ordained. Elders would not be transferred.

Priests are trained in a seminary, make the promise of celibacy, complete the full theological studies, and are employed by the diocese. Elders would be trained through weekend courses, support themselves by a secular profession, and be married. Priests live in a rectory; elders would live in their own homes. Priests can be recognized by their distinct dress; elders would dress like anybody else. Priests are addressed as “Father”; elders would be addressed as anybody else.

Both kinds of priests need each other. This is why they would not endanger each other. There is no need to fear that the priests would give up their priesthood if elders were ordained, because the priests would be needed for the continued formation of the elders.

Several times in our recent past the idea of ordaining local leaders was opposed because it was feared that a change of the priesthood somewhere would create chaos everywhere. Because the creation of two distinct kinds of priests would leave the present priests as they are, dioceses that are not ready to ordain teams of elders need not fear that they would be negatively affected if a neighboring diocese took this step.

This danger certainly would exist if priests and elders fulfilled the same role, but they would have different roles. There is no need to fear chaos. The change could be confined to a particular diocese.

As already mentioned, more than half the Catholic Church’s communities have no resident priest. This is especially the case in Asia, Africa, and Latin America but also to some extent in Europe and North America.

A great number of these “self-ministering” communities are ready or almost ready for the introduction of teams of ordained elders. They already have teams of trained leaders, and they have priests who are used to continually training these leaders.

Ordaining proven local leaders could thus be the starting point for a solution. Because the majority of proven local leaders are women, it is unavoidable that the question of their inclusion among ordained elders will arise, though present church law does not permit it.

Many dioceses may be far from ready to introduce the ordination of elders. If some dioceses could take this step, though, it would be a powerful sign of hope. Other dioceses and parishes could then see how they should develop, in the hope that we can all overcome the present shortage of priests.

And the survey says…

(Note: Results are based on survey responses from 545 U.S. Catholic readers and website visitors. Advance copies of Sounding Board are mailed to a sample of U.S. Catholic subscribers. A representative selection of their comments follows.)

1. I think ordaining local elders would be a good way to solve the priest shortage.

Agree – 65%

Disagree – 20%

Other – 15%

Representative of “other”: “I think the church would be better served by allowing priests to marry rather than creating another class of ministers.”

2. If men could be ordained as elders, they’d be less likely to become traditional priests or deacons.

Agree – 38%

Disagree – 50%

Other – 12%

Representative of “other”: “It would depend on their calling/charism. We should trust the Holy Spirit in this.”

3. Ordaining elders might be a good idea for the developing world, but it’s not a feasible solution in the United States.

Agree – 19%

Disagree – 72%

Other – 9%

4. Bishops should be empowered to implement local solutions to the priest shortage (such as elders) rather than having to wait for a universally accepted solution from Rome.

Agree – 67%

Disagree – 25%

Other – 8%

5. I worry that someday my community will not have access to the Eucharist every Sunday due to the priest shortage.

Agree – 60%

Disagree – 31%

Other – 9%

6. It is better to uphold our long-standing requirements for the priesthood than to change the rules, even if that may mean fewer sacramental celebrations.

Agree – 12%

Disagree – 83%

Other – 5%

7. To overcome the priest shortage, I think the church should:

End the celibacy requirement for priests. – 74&

Ordain women. – 69%

Ordain elders. – 63%

Encourage more prayer for vocations. – 40%

Allow short-term commitments to the priesthood. – 27%

Increase efforts to recruit men. – 23%

Other – 12%

This article originally appeared in the March 2010 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 75, No. 3, pages 22-26).

Image: Tom Wright

Add comment