As church leaders turn up the volume on same-sex marriage, gay and lesbian Catholics find themselves wondering just where they stand in their church.

On a clear, windy Sunday in March 2010, Father William Breslin told his parishioners at Sacred Heart of Jesus in Boulder, Colorado why the parish school would not re-enroll a child of same-sex parents for the coming school year.

“I hate the fact that I had to make a choice between being loving and protecting the teachings of the church,” Breslin told Mass-goers. “The lesbian couple is saying that their relationship is a good one that should be accepted by everyone; and the church cannot agree to that.” Breslin added that he saw ample love all around Boulder, but “a scarcity of discipleship. . . . I chose to protect the faith over doing what would have looked like the loving thing to do.”

In the pews, Shawn Reynolds, a gay parishioner, remembers that he shut down during the homily. He left at communion and hasn’t returned. “Pastors are supposed to tend to the flock, not disperse them,” he says.

Incidents like this one lead some gay and lesbian Catholics to wonder if there’s a future for them in today’s Catholic Church. The past decade has brought a number of disappointments to these Catholics, who had hoped for greater acceptance and a greater emphasis on love.

They point to the U.S. bishops’ 1997 document Always Our Children, comparing it to what has been understood as the harder line of a 2006 document, Ministry to Persons with a Homosexual Inclination. They find other evidence of the church’s harsh official position in the prohibition in 1987 of DignityUSA (the oldest advocacy organization for gay and lesbian Catholics) from meeting on church property and the 2006 Vatican decision that gay men called to the priesthood would face greater barriers.

Arthur Fitzmaurice, who has been active in gay ministry in the Los Angeles area and is on the board of the Catholic Association for Lesbian and Gay Ministry (CALGM), sees the messages from the bishops as unbalanced and unhelpful. “Being gay has been a gift from God,” he says. “Neither they nor I can put down what God has given me. But the bishops’ silence or negative rhetoric is driving people away.”

Opposite sides of the aisle

The gulf between the bishops and gay and lesbian Catholics plays out most starkly in the battle over same-sex marriage, the most prominent gay rights issue in the United States today.

Philadelphia Archbishop Charles Chaput has written that the church teaches that “sexual intimacy by anyone outside marriage is wrong; that marriage is a sacramental covenant; and that marriage can only occur between a man and a woman. These beliefs are central to a Catholic understanding of human nature, family, and happiness, and the organization of society. The church cannot change these teachings because, in the faith of Catholics, they are the teachings of Jesus Christ.”

“Sexual intercourse is allowed between a husband and wife in marriage,” says Bishop William Skylstad, apostolic administrator of the Baker Diocese in Oregon. “The rest of us are asked to be celibate. That teaching is not focusing on gay people, it’s everyone outside marriage. It’s been a long-standing teaching within the church.”

The church has in many states put itself in the political forefront against same-sex marriage. “Marriage is now the front line in this particular battle of the culture war,” says Father James Livingston, a priest in the Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis.

But if this is a battle, the church is clearly going to need both better strategy and communications.

When Minnesota’s Catholic bishops sent out 400,000 anti-same-sex marriage DVDs to Catholics across the state in autumn 2010, coinciding with the campaign of a gubernatorial candidate opposed to same-sex marriage, the fellow lost to the candidate who was in favor of same-sex marriage rights.

“It backfired,” says Benedictine Father Bob Pierson in Collegeville, Minnesota. “It was seen as hurtful by a lot of people.”

Even Catholics who aren’t gay or lesbian are in profound disagreement with the hierarchy regarding the issue. A March 2011 report from the Public Religion Research Institute found Catholics to be more supportive of legal recognition of same-sex relationships than any other Christian denomination—more than the general public, even. In addition, 60 percent believe that same-sex couples should be allowed to adopt.

The report found Catholics to be more critical than other religious groups about how their church is handling the issue. Catholics are less likely to hear about homosexuality from the clergy, but when they do hear about it, more are likely to say the message was negative. And when same-sex marriage is defined as a “civil union,” 71 percent of Catholics support it.

Archbishop Joseph Kurtz of Louisville, Kentucky doesn’t believe it. “In states where people have voted, they’ve voted against it,” he says. “That’s a truer poll.”

Marianne Duddy-Burke, executive director of DignityUSA, believes the polls. She says that since the 1990s polls have shown Catholics to be in the forefront of accepting GLBT (gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender) people. She points to three reasons: the social justice tradition in the church, the importance of family and community to Catholics, and the fact that Catholics are generally well educated. The higher a person’s education level, the more likely he or she is to be supportive.

Mixed messages

There is common ground between GLBT Catholics and the church. “Every conversation should emphasize dignity,” says Kurtz, past chairman of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops’ Ad Hoc Committee for the Defense of Marriage. The archbishop praises the USCCB’s Ministry to Persons with a Homosexual Inclination, which begins with general principles, the first of which is respecting human dignity, that (quoting from the Catechism) “persons with a homosexual inclination must be accepted with respect, compassion, and sensitivity.”

However, that document also advises that a person’s revelation of any “homosexual tendencies” should be confined to certain close friends, family members, a spiritual director, confessor, or members of a church support group. It also notes “the homosexual inclination is objectively disordered, i.e., it is an inclination that predisposes one toward what is truly not good for the human person.”

That phrasing is less bleak than a 1986 Vatican letter, which stated that while homosexuality isn’t a sin, it is a “strong tendency ordered toward an intrinsic moral evil.” It is certainly less positive than Always Our Children, which ended with this concluding word “to our homosexual brothers and sisters”: “Though at times you may feel discouraged, hurt, or angry, do not walk away from your families, from the Christian community, from all those who love you. In you God’s love is revealed. You are always our children.”

Not all gay Catholics are disaffected. Gay Catholic blogger Steve Gershom (a pseudonym) believes that he travels in very different circles from gays and lesbians who are angry and hurt by the church’s teachings on homosexuality and same-sex marriage. He believes that part of the difference between himself and gay Catholic activists is that he doesn’t identify primarily as gay, in the way he identifies as Catholic, or as a man or human.

Gershom doesn’t believe that the gay lifestyle is compatible with Christianity, nor does he believe that church teaching will ever change. “If you believe as I do, that the church is infallible, then it’s simply impossible to say that she can make a mistake in dogma and that she can change,” he says. Gershom’s blog attracts many gay readers who agree with him.

Other gay and lesbian Catholics are hurt by the church’s current message.

“We still have a ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ policy in the church,” says a gay teacher at a Catholic high school—who, along with several other people and parishes, requested to remain anonymous for this story.

“There is a tension in the church’s teachings on homosexuality, between condemnation of homosexual acts, and the emphasis on the dignity of homosexual people,” says Frank DeBernardo, head of New Ways Ministry, another prominent gay-positive group for Catholics. (New Ways is also rejected by the bishops; its founders, Sister Jeannine Gramick and Father Robert Nugent, were ordered by the Vatican to disassociate themselves from the group in 1999). “It’s all going to come down to a question of emphasis. I fall on the side of believing that the dignity of all people, including gay people, is a more essential teaching than the teaching on sexual expression. But the bishops never emphasize that teaching.”

“Both are to be emphasized, the dignity and the Catholic vision for sexuality,” says Kurtz.

Gershom has heard the bishops emphasize both, but others have missed it. Fitzmaurice, for instance, faults the bishops for not taking advantage of teaching moments following several recent suicides of gay teens after being bullied over their sexual orientation. The bishops could have spoken out on bullying, says Fitzmaurice.

Keeping connected

Kurtz and Skylstad both say they would counsel gay and lesbian Catholics by first listening. “I remember my history as a priest, talking with people who had been rejected by family for their orientation,” says Skylstad. “That is very wrong. It was terribly difficult and painful for them.”

Kurtz says he would begin the conversation with gay or lesbian Catholics with Ministry to Persons with a Homosexual Inclination and its principles.

Problematically, many gay Catholics, and increasingly their families and neighbors, have decided that those principles and the document are misguided.

“I’ve been in a relationship with my partner for 17 years,” says Javier Ortega, who once worked in outreach to gay Catholics but no longer goes to Mass. “Shouldn’t the church want me to marry my partner? It’s sad to see that people are still tormenting themselves to the point of suicide. That added to all the abuses—it takes down my faith in the leaders of the church. Not in the church but in the leaders.”

“That’s the kind of thing that the bishops don’t think about,” Duddy-Burke says. “The damage that can be done to people is horrific—and the unfortunate thing is that people just walk away from the church.”

Younger gay Catholics are leaving, she says. They feel accepted and more comfortable in the Episcopal Church, or the United Church of Christ.

“It is terribly sad that people are driven away by what they feel is hatred or bigotry,” says Gershom. “But I see that as confused thinking.”

Part of the divide comes from different diagnoses. DignityUSA’s 1970 founding principles include, “We believe that homosexuality is a natural variation on the use of sex. It implies no sickness or immorality.” The American Psychiatric Association agreed in 1973, removing homosexuality from its list of psychological disorders. The Vatican, however, still judges homosexuality to be “intrinsically disordered.”

Fitzmaurice says that when he talks with people about the church, he tries to share positive teachings—on chastity in marriage, for instance. “If you focus in the moment, you hear hurtful language that’s not trying to shepherd us, not trying to know us,” he says.

Gay and lesbian Catholic leaders like Fitzmaurice work hard to keep GLBT Catholics in the church. The parish and the pastor are key to that goal, says Father James Schexnayder, another CALGM board member from the Diocese of Oakland, California.

Schexnayder has written a book, Setting the Table: Preparing Catholic Parishes to Welcome Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People and Their Families. He notes that while a number of parishes have a reputation for being welcoming to gay and lesbian Catholics (one list of those parishes appears on New Ways Ministry’s website), most don’t have specific programs for gay and lesbian parishioners—and many would like to begin programs that go beyond welcoming. Many times the parishioners behind such an impetus are parents of GLBT children. Shexnayder describes welcoming parishes as emphasizing how GLBT Catholics can be inspirational for others.

A place at the table

Joy Wallace says her current parish, St. Andrew’s in Portland, Oregon, has brought in a number of new GLBT Catholics through its Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults (RCIA) program. Wallace herself became a Catholic through a welcoming parish nearly a quarter century ago. She had begun volunteering with Coming Home Hospice in San Francisco’s Castro District, assisting and comforting people dying of AIDS. She saw many of her fellow volunteers coming or going from the church across the street, Most Holy Redeemer. “It was the first time I’d ever seen Christians living their faith,” she said.

She didn’t join them. Her father had warned her about Catholics.

When Wallace lost a patient she had come to love, though, she was devastated. “I felt I’d been ripped open, all black inside,” she says.

Wallace tried various balms, but nothing worked. Then she agreed to attend a memorial service at Most Holy Redeemer. “I sat on Mary’s side of the church,” Wallace remembers. “I sobbed through the whole thing. I knew I was home.”

Wallace moved to Portland and found a supportive parish there. “When people ask me, a feminist and a lesbian, how can I be a Catholic, I have to say there’s no logic. It’s truly a heart issue. I’m nourished by my community, and I’m not letting anyone take that away.”

Other gay Catholics find that through DignityUSA. “Ten years ago, I would not have checked out Dignity,” says the high school teacher. “It had a reputation of being too far out there. My experience is that’s not the case. It’s provided me a spiritual community of gay Catholics.”

Frank DeBernardo of New Ways says some dioceses have shut down or merged ministries to gays and lesbians with other ministries in recent years, usually presenting the action as a matter of budgetary necessity. Of greater concern, he says, are new diocesan ministries. Both Colorado Springs, Colorado, and Baltimore have recently instituted Courage as their diocesan ministry to homosexuals—as recommended in Ministry to Persons with a Homosexual Inclination.

But Courage’s program begins from the wrong place, says Pierson of Minnesota. “It says, ‘my sexuality is a problem that I need to deal with in my life, an illness that needs to be healed.’ Most gay and lesbian people don’t accept that as a starting point.”

“It was modeled after AA,” says one gay Catholic, requesting anonymity. “But there’s no such thing as a loving act of alcoholism. It’s not a fair comparison. Part of the conversation was, ‘How long since your last sexual encounter?’ I wasn’t sexually active, and so it wasn’t something I could identify with.”

Fitzmaurice took part in a Courage online forum. He remembers that there were people writing about suicide attempts and drug and alcohol abuse. “It was about addictive behavior,” he says, “and people struggling with not having an integrated personality. I think there’s a place for Courage. But there’s so much more ministry that needs to happen. And I don’t agree with shaming people about their sexual behavior. That’s not what God wants.”

Livingston leads a Courage group in Minnesota. He says individuals in that group have found life and healing in the church’s message. “It was their path back to a deeper relationship with the church. They don’t identify themselves as homosexual people; they see themselves as people having homosexual issues in their lives. I have to believe in their witness. But I don’t think they characterize the general [gay] population. I work with a minority of a minority: people with same-sex attraction who are practicing chastity in their lives.”

Hope for the future

Some gay and lesbian Catholics, like Gershom, have embraced the church’s teaching on homosexuality, believing it will never change. Gershom has written that he’s found a way to be joyful in his vocation as a celibate, faithful Catholic. Other gay and lesbian Catholics have also taken the bishops at their word—and have left the church. A third group, also remaining in communion with the church, isn’t so sure.

“I have high hopes,” says the high school teacher. “I think in time the church will change, just as it changed on the science of Galileo. Someone pointed out that the Bible justifies slavery and subordination of women; we tend to ignore those passages.”

Livingston envisions change of a different sort. “The gay energy movement impetus is a little like an economic bubble; I don’t think it can sustain itself. The ideology behind it isn’t sustainable because it ultimately isn’t natural. Maybe this is a misguided generation, but I have an optimistic view. The Holy Spirit stirs up people, generation to generation.”

He is concerned, however, about the potential inability of Catholic Charities and other faith-based adoption services to continue their work in a culture that sees them as discriminatory.

“We don’t necessarily know the implications of changing the definition of marriage,” warns Kurtz. “Part of the work of the church is to promote the pastoral initiative on the public nature of marriage. It has eroded into being private. Marriage will always be deeply personal, but it’s not private.”

Duddy-Burke and her partner Becky would agree. The older of their two adopted daughters has arrived at the age of sleepovers. When family after family recently dropped off kids at their home, Duddy-Burke says she and Becky were moved. Not one of those parents seemed worried that they are a lesbian couple. “It’s because they know us,” Duddy-Burke says. “We’re part of the community. We work alongside them in the parent-teacher organization.”

“The situation is not as bad as it has been,” says Pierson. “I believe that the Holy Spirit is in charge, and I believe that our leaders are trying to listen to the Holy Spirit. But I’m also realistic enough to know that this could be really difficult, especially in the short run.”

This article appeared in the March 2012 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 77, No. 3, pages 12-17).

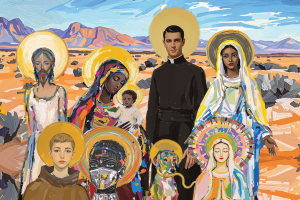

Image: Tom Wright

Add comment