Growing up in an evangelical Protestant family, I didn’t hear much about the Christian mystics. My religious background tended to equate mysticism with occult practices, overlooking the mystics’ real emphasis: a direct experience of God. Yet, I sensed that the divine was a constant, companionable presence, someone who was simultaneously both within and all around me.

Then, in my 20s, I picked up a book about Julian of Norwich. In Julian, I felt as if I’d found a friend, someone wise and intelligent I could respect and admire. She’d clearly thought so much more deeply about God than I ever had, and she had examined her own experiences with such care and thoroughness that I trusted the conclusions she reached. When she said God is intimately concerned with our lives, I believed her.

Since then, I’ve read and reread her account of her visions (her “showings,” as she called them), and each time I’ve felt I was getting to know her—and myself—a little better. Though our lives are separated by centuries, she is my spiritual mentor. At each phase of my life, I have felt a new connection with her.

Though we don’t know many details about Julian’s life, what history does tell us is that by the time she was a young woman, three outbreaks of the plague had hit her community. I’ve never experienced the extreme sorrow and trauma she must have, but as a young woman I was terrified of death—not my own, but others’. My older brother died when I was a teenager, and as a result I saw the world as a place of uncertainty and danger.

In Julian, though, I found an assurance I could trust. She didn’t claim that life would always be free of loss and sorrow; clearly, she knew how dark and terrible life can be—and yet she wrote with such joyful certainty: “All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of things shall be well.”

When I became a mother, I gained still another understanding of Julian’s theology. With an enviable disregard for gender, Julian wrote that Christ is the only human who totally epitomizes the word mother: “It is Her work to keep us safe; it is Her honor to work for us; and it is Her will that we know what She is doing, for She wants us to love Her and trust Her.” Reading her words, I understood God’s love in a new way, as something as simple and joyful as my love for my babies and theirs for me.

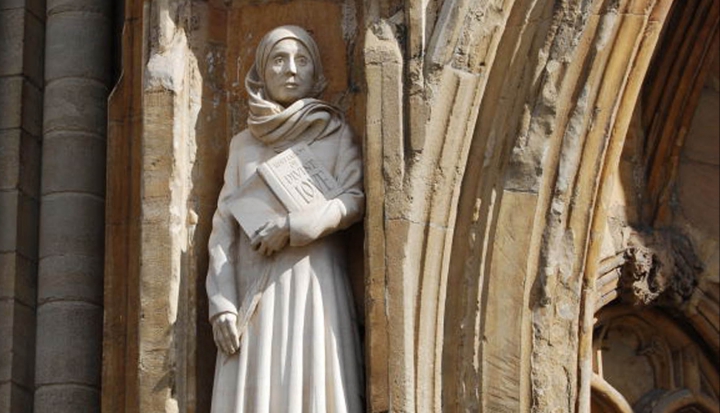

Julian’s intense mystical revelations changed her life forever, giving her a new understanding of God and her relationship with the divine.

She became an anchoress, which meant committing to a life of prayer and meditation while confined for the rest of her life to a cell adjoining a church. Her only access to the external world was three windows: one into the church, through which she participated in Mass; one into the community, through which she could talk with visitors; and one that looked into an adjoining room, where a servant lived. Unlike Julian, the servant could come and go, entering Julian’s suite to bring food and do the cooking and cleaning, so that Julian’s time could be devoted completely to prayer and spiritual counsel.

I have never experienced anything close to the claustrophobia Julian must have known as an anchoress, but any time I felt restricted and confined by my professional responsibilities, I found myself turning once more to Julian. In the morning, before my workday began, I spent time with Julian’s writing, translating the Middle English into modern language. As I went back and forth between her original words and Middle English dictionaries, I connected even deeper with my old friend and mentor.

After Julian’s visions, she spent the next 20 years analyzing them, deciphering their meanings. At the same time, she may have learned to read and write, and then gone on to read some of the greatest books of theology that were available in her day. If the narrow walls of her anchorage could become for her a place of intellectual and creative freedom, I realized that I too could find ways to move into a new and more fruitful phase of my writing career.

As the years passed and I moved into other life phases, Julian’s ideas continued to challenge and inspire me. A few years ago, my mother, father, and mother-in-law died within the space of 18 months, leaving me submerged in an intense depression. One day, as I reread Julian’s book yet again, I saw that she too had experienced times of deep sorrow. “As best as I can understand,” she wrote, “the purpose . . . was to show that our souls are driven forward by the emotional cycles we all experience: sometimes we are comforted, and sometimes we feel we have been abandoned. God wants us to understand that our emotions are not reality. The Divine One keeps us equally safe in sadness and in happiness. . . . Like any temporary pain, these sensations are to be endured until they pass.” Slowly I emerged from my depression and could accept, as Julian said, that “God allows us to feel a range of emotions—but they are all expressions of Divine love.”

Today Julian inspires me in new ways. She firmly believed her visions were not for her alone: They were for all of us. As an anchoress, she chose living burial, yet continued to be an active member of her community. Rich and poor came to her window seeking her advice and guidance, and her sense of community shines through her writing. She challenges me to seek the same balance of spiritual solitude and active community involvement, with each supporting and nourishing the other.

Julian concludes her book with this realization: “Love was God’s meaning. Who showed you these visions? Love. What were you shown? Love. Why were you shown these visions? For love. Hold on to that love, and you will learn and understand more of the same love—but you will never learn nor understand anything else.” Once again, I have to agree with Julian. The constant presence I felt as a child was love, always present both within me and all around me.

“This book was begun by God’s gift, by Divine grace,” Julian wrote on her final page, “but I do not believe it has yet been finished. It is still developing and growing.” I am grateful that 600 years later, it is still growing in me.

This article appears in the May 2016 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 81, No. 5, pages 45–46).

Add comment