An epic quest for cultural identity unfolds in the pages of Gene Luen Yang’s graphic novels.

When Pope John Paul II canonized 120 Catholics from China in 2000, a Chinese American Catholic community celebrated in San Jose, California. Graphic novel author Gene Luen Yang recalls his parish’s elation that 88 of the new saints were ethnically Chinese. “It was the first time the Catholic Church had acknowledged Chinese Catholics in this way,” he says.

Many of those saints died in the Boxer Rebellion, the late-19th-century peasant uprising in China against the foreign and Christian presence there. For Yang, the son of Chinese immigrants to California, the canonization spurred a strong interest in learning about this historical event. In 2013 he published a two-volume epic based on the events of the Boxer Rebellion, Boxers & Saints (First Second Books).

Graphic novels, which tell a full-length story using the art and storytelling format of comic books, are currently enjoying newfound respectability. They are the fastest-growing section in many bookstores and libraries, and many critics have come to regard them as serious literature.

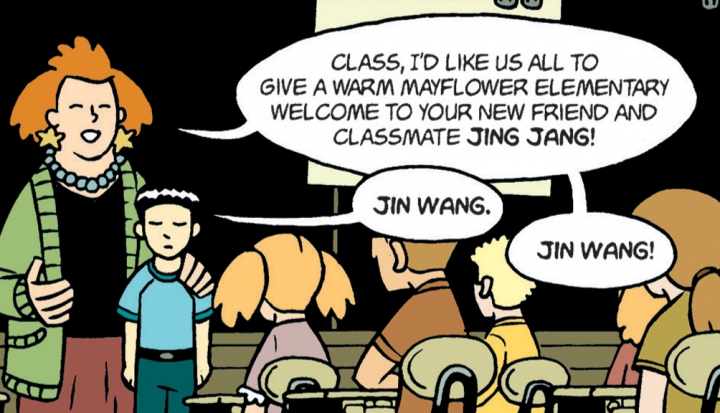

Yang, 40, has become an ambassador for this thoughtful brand of comics. He first found mainstream success with his 2006 book American Born Chinese (First Second Books), a graphic novel that draws on his childhood experiences of feeling like an outsider at school due to his ethnicity.

Drawing on experience

Weaving humor with themes of race and identity, American Born Chinese was the first graphic novel to be nominated for a National Book Award and the first to win the American Library Association’s Printz Award. It also caught on as a favorite in libraries and schools.

A graphic novel winning these awards is remarkable. More remarkable is that Yang almost didn’t become a cartoonist. Although he was interested in comics growing up, his father, an electrical engineer from Taiwan, told him to choose a “practical” major—meaning the sciences. Like many immigrant parents, Yang’s father wanted a stable career for his son instead of the life of a struggling artist. “It definitely rubbed me the wrong way,” Yang says.

Yang dutifully majored in computer science and found a job as a software programmer. But he remained smitten with cartooning. He eventually quit his job to work on his comics. He now supplements his art with a part-time job managing databases for a Catholic high school in Oakland—an arrangement his father has accepted, if reluctantly.

Between two worlds

Yang’s conflict is one that many children of Asian immigrants know well. Inherited Confucian values can leave them feeling caught between honoring their parents and pursuing their dreams, contributing to their sense of alienation.

Another tension emerges in Boxers & Saints. As Yang read more about the violent history of the Boxer Rebellion, he found a complicated story. For instance, the Chinese government claimed the Catholic missionaries had a corrosive influence on Chinese culture, and even protested their canonization.

Yang found his sympathies wavering between the anti-imperialist rebels and the Chinese Catholics they killed, leading him to tell the story in two parallel books. Boxers follows the viewpoint of Little Bao, a fictional boy who grows up to lead the Boxers. The second book, Saints, focuses on a Chinese girl named Vibiana who converts to Catholicism.

Historical fiction was new territory for Yang, and he was nervous about getting the details right. “I was freaked out right before it was published,” he admits. Those fears have proven unfounded. Since its 2013 release, Boxers & Saints has picked up numerous honors and recently won the prestigious Los Angeles Times Book Prize, making it the first graphic novel ever to win in a non-graphic novel category.

East meets west

Yang counts Catholic spiritual writers such as Henri Nouwen and Shūsaku Endō among his literary influences, and he speaks comfortably about his faith. After a period of spiritual searching, he found a vibrant faith in college through InterVarsity Christian Fellowship, a student ministry. He worked as a campus minister with the organization for a year after he graduated.

Still, Yang’s only obviously religious work is The Rosary Comic Book (Pauline), an illustrated guide to praying the rosary. He prefers not to write about faith directly, finding that it naturally emerges when he writes about life. “There’s an underlying spirituality in every story we tell,” he says.

Success has opened new doors for him, like being tapped to write the popular Avatar: Last Airbender graphic novels and spending summers teaching in the master of fine arts program at Hamline University in St. Paul, Minnesota. But Yang is still fascinated with identity. His latest work, The Shadow Hero (First Second Books), is about a Chinese American immigrant who becomes a superhero.

Yang concedes that his ethnicity and faith can sometimes make for an awkward pairing. He once was asked why he would turn his back on the beauty of Eastern religions to embrace Catholicism. The question stuck with him. And yet he finds in Christianity something he says is absent in Eastern faiths—the theme of “divine intention,” that one’s identity is superintended by a higher power.

That’s good news for those who feel like outsiders. “For people who grow up in between cultures, we often don’t feel at home in either one,” he says. “You can’t find a home in either culture, so you find a home in the divine will.

This article appeared in the September 2014 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 79, No. 9, pages 47-48).

Image: Courtesy of First Second Books

Add comment