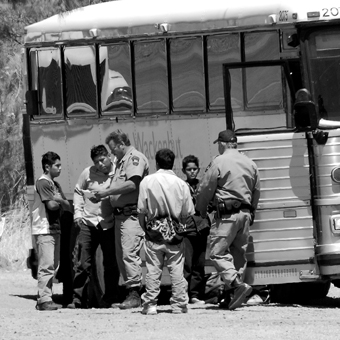

Arizona's immigration crackdown both was inspired by and inspires fear.

"Panico." That's how Joel Navarette, the coordinator of the youth group at St. Agnes Church in Phoenix, describes the reaction to SB 1070, an immigration crackdown that Arizona Gov. Jan Brewer signed into law in April.

Despite opposition from the U.S. bishops, polls have shown broad local and national support of the law and desire for similar legislation in other states.

Navarette says the young people in Phoenix, whether legal residents or not, didn't know what to make of the law. "It was the way pundits were talking about SB 1070," he says. "The community didn't know how it was going to work. They didn't know what to do, except leave the state."

A noticeable number did flee, either to Mexico or elsewhere in the United States, he says. "They didn't want to stay here with so much division, with the possibility of humiliation."

Fear also fueled support for SB 1070, especially after borderland rancher Rob Krentz was shot and killed 30 miles outside of Douglas, Arizona nearly a month before the bill passed. Authorities suspect drug smugglers, though no arrests have been made.

As it was written, SB 1070 would have made it a state crime to be in the United States illegally—a violation of civil codes under federal law. The law has changed through amendments, and federal judicial action blocked controversial aspects of the bill on July 28, a day before it took effect.

Now police are not required to verify immigration status on stops, and immigrants are not required to carry proof of their status by the state (the state hoped to enforce this, as federal law requiring proof of status is not enforced).

But Arizona residents can sue state offices or agencies for failing to fully enforce immigration laws, effectively blocking "sanctuary city" policies that prevent police or government employees from asking about immigration status. Human smuggling, picking up day laborers, and knowingly employing undocumented workers are now state crimes.

The Justice Department lawsuit argued that SB 1070 was "preempted by federal law." Supporters of the law, however, said that the failure of U.S. government to enact immigration reform was a driving force behind Arizona's law.

Arizona bishops released a statement applauding the judge's decision while calling for national reform. "The tragic consequences of the failure of our nation's political leadership to enact reform of our immigration system have included the deaths of thousands of people," the statement says. "Migrants—women, men, children in desperate circumstances—have died trying to enter our country. U.S. citizens have died because of crimes committed by drug smugglers, people smugglers, and weapons smugglers."

While fear has subsided since the judge's ruling, Navarette says it isn't gone. Youth group members no longer go out to dinner after meetings, and undocumented members don't drive.

What's needed most is information. The Phoenix diocese's Office of Hispanic Ministry organizes information meetings on SB 1070 at parishes throughout the state. With 200 to 300 attendees, they cover the rights of undocumented immigrants, calming undocumented parishioners.

Churches should also be places where opposing sides can hash things out, according to Joe Rubio, Arizona senior organizer of the Industrial Areas Foundation. "The church can be a very powerful force in helping to bring together the different sides," he says. "We don't all have to come at it from the same direction to realize the system is broken and needs to be fixed."

Carole Bartholomeaux, a parishioner at St. Joseph Church in Phoenix and a supporter of SB 1070 agrees. "If our republic is to survive, there must be common ground on this highly divisive issue," she says.

With a fifth of Arizonans living in poverty, supporters of SB 1070 argue that undocumented immigrants have taken a toll on the state's economy. "Arizona can no longer afford to support those who do not contribute to the cost of running the state," Bartholomeaux says, falsely claiming that the undocumented "pay no taxes."

The Immigration Policy Center reports that 50 to 75 percent of undocumented immigrants pay state and federal taxes, not to mention sales and property taxes. "Particularly when there's an economic downturn, we're always looking for a scapegoat," Rubio says.

In Arizona and nationally, talk has shifted from SB 1070 to a questioning of birthright citizenship. Some say the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution doesn't guarantee citizenship to everyone born in the United States.

Meanwhile, talk of comprehensive immigration reform on a national level has dulled to a murmur.

"We're in danger of deporting our principles," Rubio says. "We need to reframe the discussion so that we understand the vital contributions that immigrants make to this country, to our economy, and to our parishes."

This article appeared in the December 2010 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 75, No. 12, page 33).

Image: Photo by Karl W. Hoffman

Add comment