A church historian explains why the events of the 1960s still echo through the church 40 years later.

Mark Massa, S.J. was 14 years old on the First Sunday of Advent, 1964, when Catholics across the country arrived at Mass to find the priest facing them across the altar and—even more jarring—speaking in English and expecting them to respond. The disappearing Latin Mass was but the first of many old certainties that would be blown up during the next few years.

Soon Catholics would open their morning newspapers to see photos of men in Roman collars protesting the church’s birth control teaching, or burning draft records and running from the FBI. Nuns, sans habits, departed Catholic classrooms to march for civil rights or against the war in Vietnam.

Massa, dean of the Boston College School for Theology and Ministry and founder of Fordham University’s Curran Center for American Catholic Studies, has spent the last 10 years analyzing the Catholic experience in the United States since World War II. His latest book, The American Catholic Revolution: How the ‘60s Changed the Church Forever, explores how the upheavals of that decade unleashed among Catholics a new consciousness that everything in history could change—even the Catholic Church. The events of the 1960s, says Massa, dramatically altered American Catholics’ relationship to their church, helped along by the always dependable law of unintended consequences.

Why should Catholics today care about the 1960s?

The ’60s changed almost everything in American culture: rock music, literature, the youth culture, the rise of the feminist movement, the civil rights movement, the antiwar movement. But there was also a distinctly Catholic take on the ’60s. From my point of view the Catholic ’60s are not the years from 1960 to 1970, but what I call “the long ’60s,” from the implementation of the first liturgical reforms of the Second Vatican Council in 1964, to 1974, when the Jesuit Avery Dulles published Models of the Church.

The ’60s began a whole succession of events whose ripples are not just ripples anymore; they are more like tsunamis affecting American Catholic communities today.

How would you describe Catholics in the United States during the lead-up to the 1960s?

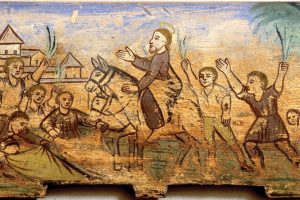

One of my favorite paintings used to hang in a Jesuit retreat house in Boston: It’s Jesus at the Last Supper. All of the apostles are kneeling around him and he’s putting the wafer on their tongues.

There was a sense in 1960 that what Catholics did on Sunday morning was pretty much what Jesus did with the apostles on Holy Thursday. That sense of timelessness aligned with the fact that most Americans don’t know and aren’t interested in history.

The period between the First and Second Vatican Councils, from about 1860 to 1960, was an anomalous time because Catholicism remained much the same. Most American Catholics thought that’s how it had always been.

In his book Bare Ruined Choirs—a bittersweet and sometimes whiny account of the ’60s—historian Garry Wills says that in Western culture the dirty little secret was sex. But in the church the secret was change.

When the church couldn’t explain change, they buried it and started documents by saying “Have we not always said . . . ?” As a historian, I can say, “Actually you have not always said that.” Sometimes the changes were quite dramatic. That came as a blast of new information for most Catholics.

So what happened in 1964 to start it off?

The First Sunday of Advent in 1964 was the line in the sand for the church in the United States. On that Sunday the Mass was said in English for the first time, and the priest began facing the people again, which was the tradition of the early church and had been the case in St. Peter’s Basilica for centuries.

Wills writes, “It was like going to a house of alien occupancy.” It was a house you knew and loved, but suddenly it was as if someone else was living there. Because there were no Catholic hymns, most dioceses decided to use nondescript Protestant hymns. I think priests were very ill prepared to explain to their congregations what was going on. Some of the bishops, even those most in favor of the reforms, like Archbishop John Dearden of Detroit, feared that there would be a rebellion in the pews.

The surprising thing is that most people liked the new Mass. There were a few strong rejections, but the expected explosion never materialized. Sociologist Father Andrew Greeley said that within two years around 73 percent of American Catholics said they liked the changes in the liturgy, which was astonishing. Nobody expected that.

So it was a stunning change for most people in the pews?

It certainly was. Rather than praying your rosary during Mass or saying prayers for dead relatives whose holy cards you had stuck into the pages of your missal, suddenly the priest is saying, “The Lord be with you,” and you have to answer him. People realized that they were supposed to be paying attention to what the priest was doing; they were expected to be part of the great prayer of the church. That was really jarring.

My father hated the new liturgy. The first couple of weeks he was so depressed about having to sing Protestant hymns and respond in church. Twenty years later I was home when the diocese was having a Tridentine Mass as part of the 20th anniversary of the reforms of Vatican II. We went, and afterward he said, “How did I put up with that for 40 years?”

People put up with it precisely because they thought it was timeless. Then it changed. My undergraduate students, who grew up in a world where this is just part of the furniture in the church, don’t realize how traumatic this was in 1964.

And yet how traumatic could it be if a couple of years later 70 percent of the people thought it was great?

It was traumatic not in the sense that lots of people lay on the sidewalk in front of their parishes and demanded the Latin Mass back. But more than any other single event, what the liturgy made Catholics aware of is that the tradition changes.

To realize that and then to have a church leader say, “But you can never have married priests,” the response now becomes, “Well, why not?” It makes the answer from authority—“Do this because I tell you to”—difficult.

The answer from authority works if you say, “I’m authoritative because I speak for the tradition that is unchanging.” It works less well if you say, “I speak for a tradition that was this way for 100 years and then we did something else and then we did something else.” That makes it more difficult to hold the line and say, “No, we’re not even going to talk about this.” People say, “Well, why not? Why can’t we talk about it?”

The changes in the Mass did more than change how people worshiped on Sunday morning. It had a much larger impact on how they perceived the world.

What about those who say Vatican II is responsible for the fact that fewer people come to church and even fewer are entering religious life?

We could still be sitting at this table when Jesus comes and not be finished talking about what caused the fall-off in religious vocations.

There are certain events that came out of the ’60s that did in fact lead to Catholic disaffection, but I’m pretty sure Vatican II wasn’t one of those. I would say Vatican II in a sense saved the U.S. church.

To say that if we hadn’t changed anything, our churches would still be packed is a specious argument. I think things were about to collapse in on themselves. American Catholics were leaving immigrant neighborhoods and moving to the suburbs where their neighbors might be Jewish or agnostic and they had to learn to get along. Vatican II simply confirmed in their minds that the older, tighter model of the immigrant, conformist church was not in fact what faith was all about. Vatican II came as a welcome oasis in the desert.

I agree with Greeley that a bigger cause of Catholic disaffection was Humanae Vitae, the document that prohibited artificial birth control. The reception of that papal encyclical in 1968 set off the kind of internal theological debates that the church had not experienced in 500 years.

How did the Humanae Vitae decision come about?

Pope John XXIII had called together a very select blue ribbon panel including Pat and Patty Crowley of Chicago, founders of the Christian Family Movement. That panel recommended, by a substantial majority, to change the church’s teaching on birth control.

The ironies here are delicious because the person who came up with the pill was John Rock, an Irish Catholic doctor who worked in Boston and who was a daily communicant. He thought the church would embrace the pill because it uses ovulation cycles, so it would fulfill natural law.

I think Pope Paul VI was afraid of changing that teaching because if he did so, it would have opened up the question of how we could have been so wrong about this for so many years.

Ironically, by holding the line, that is precisely the question that people began asking. According to Greeley’s statistics, people in the 1950s were already using birth control—not the majority, but a substantial minority of Catholic couples. By 1968 it was not even on the table anymore.

Sociology tells us that the vast majority of Catholic couples said: “We want to remain Catholic, we don’t want to leave the church, so we’re just not going to pay any attention to this.”

This situation—devout Catholics ignoring an important part of church teaching, in this case on sexuality—has been tragic for all concerned: for Rome, for parish priests, for Catholic couples, for theologians.

As a church historian, and as a dean of a theological school, I would like to see how we can move toward some consensus on this isue, as it has become a fissure within the household of faith.

What was the fallout at the time?

You could almost say it was a tragedy. Sides almost immediately materialized and calcified. Those people who objected were quickly labeled as renegades.

The most well known case was Father Charles Curran, who lost his tenure at Catholic University of America over it. Curran in his own way is a fairly conservative theologian. He wrote his dissertation at a pontifical university in Rome on Alphonsus Liguori, the patron saint of confessors.

Curran was asking good moral theology questions from a confessor’s point of view. He was saying: OK, this woman comes into my confessional and she has eight children and her husband is a steel worker. What am I supposed to tell her about birth control now? You have to come up with better reasons to say birth control is immoral.

The Washington Post carried a front page photo of Catholic protesters on Humanae Vitae, all of whom were wearing Roman collars. I don’t think most Catholics had ever seen anything like that before. The idea that priests were doing the protesting was shocking, and it led many Catholics to wonder how bishops and theologians could disagree on such an important subject, and thus weakened the authority of the church to teach on other topics.

Was something more at stake than just birth control?

With Humanae Vitae the church as an institution raised the ante on sex. Humanae Vitae was the document that made sexuality the litmus test of how orthodox you are. The way you live your sexual life became the test of whether you’re Catholic or not.

Fast forward to the sex abuse crisis: When the press finds out that all these priests have not been living their vows, of course they’re delighted. This is labeled anti-Catholic; I’m sure there’s some anti-Catholicism present, but a lot of these reporters are Catholics.

I don’t want to underplay the tragedy of the abuse crisis, of course, but isn’t there an irony here somewhere?

Why were the battle lines drawn so quickly?

I think the church was afraid. Their perception was that the Catholic tradition was unchanging because it couldn’t change. This is despite the wisdom of Cardinal John Henry Newman, who said more than a century ago, “To live is to change, and to be perfect is to have changed often.”

In the 1960s John Noonan, a lawyer who was on the birth control commission and who wrote a great book on contraception, said, “It is a perennial mistake to confuse repetition of old formulas with the living law of the church.”

The Anglicans and Presbyterians had already said you could practice birth control and be a good Christian. Among Catholics there was a fear among some people—and there still is a fear—that if you allow change on this, you’re admitting that the teaching on sexuality is not changeless. I think that is most unfortunate.

So if it’s birth control now, before you know it anything goes.

Right, there’s a slippery slope, and who knows where it will lead. Now I understand a lot of the concerns. I lived in an undergraduate residence hall for six years, so I take this very seriously. I think the way we use our sexuality is important, and I don’t like to see it squandered. I don’t like casual sex and I don’t like hooking up and that whole culture. The concerns are real concerns.

Do you think the bishops at the Second Vatican Council intended such upheaval?

Father John O’Malley writes about the council and what he calls the law of unintended consequences in his book What Happened at Vatican II. His point is events have their own life and you can’t control them.

History is dangerous. Whatever the intentions of the Holy Father, he can’t control events in history. And if you change the way you talk about God, you change people’s idea of God. That’s my interpretation of ancient saying about liturgy lex orandi, lex credendi, which is one of the oldest rules of theology: The law of praying shapes the law of believing.

Can you give us an example?

If you go into church and there is an altar rail separating you from the priest, women can’t be on the altar, and the priest has his back to you, that’s a different way of encountering God than if you come in and the altar rail is gone, the priest is facing you at a freestanding table, and there are altar girls. When I was preparing for first communion, I was told you were never supposed to touch the host, yet now people take it into their hands.

I think what the council fathers believed was that you could make all those changes and still have people keep the same liturgical theology they had in 1950. But you can’t do that, because once you change the liturgy, you change the way people encounter God, and that changes the way they think about God. If suddenly my Aunt Mary can give out holy communion, I start wondering if maybe she’s as holy as the priest is.

I think the architects of Vatican II were as surprised as anyone when suddenly parish councils started becoming rambunctious, and all of these liturgical experimentations started going on. They might say: Wait a minute, we didn’t mean that. I think the O’Malley law of unintended consequences would respond: But that’s what happens when you change these things.

If you dismiss the law of unintended consequences, then you start demonizing people who think differently from the people who started the process. You don’t have to go too far down that road to see how ridiculous that is. I mean, the original Declaration of Independence and Constitution didn’t recognize slaves, but once the Constitution gathered a life of its own, we couldn’t control where that led us.

The historical process is slippery, and it isn’t logical. What the law of intended consequences allows you to see is that historical events often have their own logic, which is different from the intentions of the people behind them.

So where does that leave us today?

Now that we can all agree that historical changes happened and that the church changes, I think there has to be a long and informed debate about what kind of change is good, what kind of change is bad, what kind of borrowing from the culture is fruitful, and what kind of borrowing from the culture is deeply problematic. What makes the Catholic tradition work so well is that it takes the best aspects of culture and baptizes them and uses them to preach the gospel.

Labels are one thing the church has borrowed from the culture. Before the 1960s there were only two different kinds of Catholics: Catholics and lapsed Catholics. Then in the 1960s people started putting other adjectives in front of the word Catholic: traditional Catholic or social justice Catholic or liberal or conservative. Catholics weren’t used to thinking of themselves as being divided into those kinds of groups. But it was handy because Americans thought of themselves politically in that way.

How is that playing out?

At Boston College there’s a group of young men who get together and kneel in darkness before the Blessed Sacrament for a holy hour. In the religious community of Boston, they are called conservatives because of this. When I talk to some of them, I find they are about as far from conservative as I can imagine.

To want to find fruitful and robust liturgical traditions outside the Eucharist and maybe to resurrect some of the older ones is not to be a conservative—at least that’s not conservative in any meaningful political sense I can understand. I don’t think those political labels help us uncover what’s really going on there; in fact, they can derail the discussion.

I’m critical of these labels for three reasons. First, they’re essentially political, and they hide as much as they reveal in terms of theological issues. Second, they tend to reduce theological ideas to sound bites. And third, they lend themselves to an alliance between politics and theology that’s very dangerous, because in the United States, political-religious alliances have been toxic.

A lot of these issues lead to the question of whether we should be a big-tent church or a small-tent church.

Of course that’s the $64,000 question. Catholicism has always been the big tent. In the Middle Ages you had nominalists and realists who fought like cats and dogs at the University of Paris. Even though they debated fiercely and passionately about how their opponents were wrong in their theology, no one doubted that the people who disagreed with them were Catholics.

Mircea Eliade, who taught world religions at the University of Chicago, always said that the opposite of Catholic is not Protestant; the opposite of Catholic is sectarian. Those who want a purer, smaller church that seeks to withdraw from the world are the non-Catholics because the Catholic tradition has always been a big one.

There has always been far less uniformity of belief than we imagine. More importantly, I don’t think people live their lives based on that alone. If I stood outside St. Peter’s Church in Chicago and asked people, “Now do you go here instead of the Lutheran church because you believe in transubstantiation rather than consubstantiation?” people wouldn’t know what I was talking about.

I’ve always said that American Catholics are congregationalists. If your local parish is working, on one level it doesn’t matter who is sitting in the chair of Peter. Of course it matters, but it doesn’t matter that much on the day-to-day level where Catholics live their lives.

When theologians try to get everyone on the same page with these large intellectual categories, I think they’re missing the boat. That’s not why people stay Catholic. They stay because experientially they’ve discovered something they can’t encounter somewhere else. Why else would you bother?

This article appeared in the July 2011 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 76, No. 7, pages 18-22).

Image: Tom Wright

Add comment