During Mass each Wednesday at Casa Juan Diego in Houston, immigrants speak of not eating for days, having nothing to drink for a week, seeing people die of thirst or because they drank irrigation water with chemicals in it.

"The journey north to the border is a real Way of the Cross," says Mark Zwick, who with his wife, Louise, founded the Casa, a Catholic Worker House. "Most of the men are robbed on the way here. The majority of the women, I would bet, are violated. A man who has cancer of the eyelids but came because he has to earn money for his family said: 'It is an awful journey coming here.'"

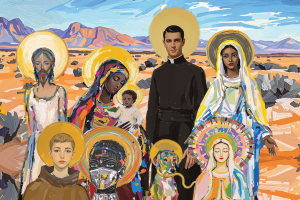

But on this Way of the Cross there are also Simons of Cyrene who help shoulder the burden and Veronicas who wipe away the blood and tears-people who, like the Zwicks, help the immigrants, who take them into their homes.

Though for most immigrants that Calvary begins in Mexico or Central and South America, for others it begins in Angola, Rwanda, Pakistan, China, or other places where death stalks. Ruben Garcia, founder and director of Annunciation House in El Paso, which provides hospitality and other services to immigrants, says: "As Kosovo is torn apart, eventually you see refugees from Kosovo on the El Paso border. It is an incredible journey but not really different from that of a Guatemalan or a Salvadoran. Whether they are from Iran or Bulgaria, Guatemala or Ecuador, they say: 'We have to migrate to survive.'"

As happened to Jesus, the journey all too often ends in death. Death comes on a deceptive stretch of the Rio Grande, by drowning, or in the deserts, where people succumb to extreme cold or heat, or to hunger and thirst. Bullets fired by U.S. Border Patrol guards or vigilantes bring down others.

Since Operation Gatekeeper began in 1994-a policy that doubled the size of the border patrol and sealed off the easiest crossings with steel walls and sophisticated surveillance technology-more than 600 immigrants have died trying to enter California. During 1998, 1999, and 2000, the Mexican Ministry of Foreign Relations counted 1,186 deaths along both sides of the entire 2,000-mile U.S.-Mexican border. (During the same time, the U.S. Border Patrol counted 861 deaths on the U.S. side alone.) The toll has risen so alarmingly that, according to news reports, border patrol guards are now receiving training in first aid and carrying water and high-energy bars to aid those in trouble.

Death, in some ways similar and in other ways different, also overtakes many in the unending stream of migrants from Mexico's interior to its burgeoning border cities. Juarez-its 1.5 million population already three times as large as that of its sister city of El Paso across the Rio Grande-receives 100 new residents every day. In the past seven years, 196 people disappeared and 215 women between the ages of 17 and 25 were murdered, crimes that remain unsolved. Maryknoll Father Paul Masson, who works in Our Lord of the Afflicted Parish, tells of a young couple stoned to death by juveniles, of a young woman attacked in her home, of a 7-year-old child kidnapped.

But there is another kind of death in the shacks of cardboard, scrap wood, or cinder block clinging precipitously to hillsides or dotting the barren desert and lacking pota-ble water, sewers, or paved streets. It is the crucifixion of an entire people by the global economy. Assembly plants, called maquiladoras, employing hundreds of thousands and owned by U.S., European, and Japanese companies, pay workers only $3.50 to $5 a day, a wage that does not even begin to cover the most basic necessities of life.

Mercy Sister Betty Campbell and Carmelite Father Peter Hinde, founders of a community of contemplation and political action called Tabor House and living in a barrio of maquiladora workers in Juarez, say it takes three maquiladora wages to support a family.

No room in the inn?

In December each year hundreds of people gather for a religious ceremony at the place where the steel wall dividing Mexico and the United States goes into the Pacific Ocean. Those from Mexico ask for refuge and the U.S. group responds, "We cannot let you in." The ceremony is a modern-day twist on the posadas, a Latin tradition dramatizing the search of Joseph and Mary for refuge on the night Jesus was born.

Last December, the participants-organized in the U.S. by the Interfaith Coalition for Immigrant Rights (ICIR), an organization with chapters throughout California, and in Mexico by the Scalabrini Fathers-read the names of the more than 600 people who died trying to cross into California since 1994.

"We try to connect the search of Joseph and Mary for a place for the child to be born with the rejection that many immigrants experience crossing the border," says Franciscan Brother Ed Dunn, a member of ICIR from San Diego.

On All Souls Day, in Mexico called the Day of the Dead, Catholics from both sides of the border gather for Mass at the fence between Anapra and Sunland Park, New Mexico. On the California border the bishops of Mexicali and Tijuana join the representatives of the ICIR in a vigil. During Lent, groups in El Paso and Juarez reenact the Way of the Cross. The underlying message of all these observances is that the border demands a response from people of faith.

At their annual meeting in November, the U.S. bishops approved a resolution urging revision of immigration laws and policies in order to legalize the maximum number of undocumented persons and respect the human dignity and human rights of all immigrants. Specifically, they asked for changes to 1996 laws that undermine due process rights, limit protection of asylum seekers, and severely restrict public benefits for legal immigrants. "At the advent of a new Congress and new administration, now is a good time to reevaluate our nation's immigration laws and policies," the resolution states.

Meanwhile, the Way of the Cross continues. The Simons and Veronicas dispense hospitality at Casa Juan Diego and Annunciation House, advocate for political asylum at an organization called Las Americas in El Paso, and struggle for human rights in the American Friends Service Committee border project in southern California.

Some Simons and Veronicas represent parishes along the border or as far away as Independence, Missouri. Others are missionaries-religious and laypeople-from Maryknoll, the Columbans, Claretians, Marists, and other groups, and some are freelancers like Mexican Dr. San Juana Mendoza Bruce, an obstetrician who has set up a rudimentary clinic built on a landfill over a former dump in Juarez.

"I am an independent worker of the Lord,"

Mendoza Bruce says, explaining that she is a full-time volunteer, dividing her time between the clinic at the dump and another one at Anapra, a dusty barrio on the barren desert on the northwest edge of Juarez.

"My husband provides my daily bread and pays my expenses. Our monthly budget includes a portion for the mission." Her husband, Charles Bruce, who has a doctorate in physics and does research at New Mexico State University in Las Cruces, built the two clinics where his wife works. "I tell him he is a man of a thousand skills," says Mendoza Bruce. "He is a carpenter, an electrician, a welder, and a plumber."

Other Simons and Veronicas can commit only their weekends, vacations, or perhaps a year like a 72-year-old retired man working as a volunteer at Annunciation House. But they are all drawn to the border by the conviction that they are taking part in something that is very important, as Maryknoll lay missioner Susan Tollefson put it.

In Juarez, Casa Peregrino, founded in 1989 by Garcia of Annunciation House, helps Mexico's internal migrants find jobs, child-care, and housing and has a program for abused women. The Community of the Holy Spirit, a mission founded for rag pickers, sells food at less than wholesale cost, provides free medical and dental care, and has a day-care center. Tollefson founded and runs the only Montessori school for the poor in Juarez.

The mission with the widest scope, however, may be that of St. Mark Parish in Independence, Missouri, now in its 17th year and started when a group from the parish responded to an invitation from Garcia.

The parish invests nearly $70,000 a year in Juarez. "This is totally funded by the parishioners themselves; it does not come from a line item in the parish budget," says Deacon Ross Beaudoin, founder of the mission. "The parish paid my salary, but I had other responsibilities, too. But as far as the direct work of the mission, that has come from the parishioners. A mission board of eight guides it."

Jim Kennedy, a retiree from the Missouri Department of Social Services became the director last year when Beaudoin went to work for the diocese. He says the parish's 1,900 families "are all very middle of the road, neither poor nor rich, just working class people."

Beaudoin says it was difficult at first because parishioners simply did not understand. "We would have raffles, bake sales, and carwashes. Nowadays we sell trash bags ('Mission is our bag') but mostly for public relations. Ninety percent of the money comes from direct donations, at least 15 percent from outside the parish and from as far away as Rochester, New York; Chicago; and Albuquerque, New Mexico. It has touched people way beyond the parish." Moreover, the parish also has a mission in Chinle, Arizona, serving Navajos, and in New Rochelle, New York, helping families of men who are in prison.

St. Mark's has two long-term missioners in Anapra, currently Kelly O'Brien and Michael Anderson. It provides scholarships to about 100 children beginning in primary grades and continuing through college. "After 6th grade the school fees run about $60 a month and $120 in high school," Kennedy says. "The families cannot afford them." The mission also pays for supplies at a dental clinic for the rag pickers and the salaries of two medical assistants at Mendoza Bruce's clinic in Anapra.

In 1997 St. Mark's built Casa de La Cruz, a large cinder block building to house various activities, its permanent missioners, and the constant stream of visitors from the parish. "We give classes in English, typing, and computer skills," Kennedy says. "The students also do their homework there. Over the years we have built about 40 cinder block houses. Five local women decide what families get assistance or houses. Every two weeks they buy a supply of rice, beans, and pasta to distribute to the most needy families. They coordinate our efforts."

Students from Jesuit Rockhurst College go there on their spring break. In May another group checks the hearing, sight, weight, and height of about 400 children. High school students, mainly confirmation candidates, go in family-size groups in the summer for two weeks to do service projects.

By now, between 200 and 300 families have participated directly in the mission. "There is a mutual sharing back and forth," Beaudoin says. "Over the years parishioners have found that their view of the world has changed, their understanding of injustice and poverty, of the reality of the border. They have found their own lives transformed by sharing in the lives of the people of Anapra, whom they see as 'our friends, our brothers and sisters, our families in Anapra.' Their beautiful sense of community, their tremendous discernment skill, has been a great lesson for all of us. Decision by consensus is the buzzword here; in Anapra they really do it."

"I was a stranger, …"

Among the Simons and Veronicas on the U.S. side one can even find officials of the border patrol and of the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) who maintain a respectful distance from Casa Juan Diego and Annunciation House, allowing them to operate.

"We are really breaking the law by working with undocumented people," admits Zwick in Houston. Recently the INS sent 31 Chinese to Casa Juan Diego. When Hurricane Mitch devastated Central America in 1999 and President Clinton suspended deportations to that area, the INS sent about 100 Central Americans each day for five days. "We housed them in a big old warehouse," Zwick says. "A motel donated 100 mattresses. Since then, the INS has been quite comfortable sending us people."

Casa Juan Diego also provides hospitality in Matamoros across the Rio Grande from Brownsville, Texas, in a community outside of Mexico City, and in Tecun Uman, Guatemala. In Matamoros, 70 communities in the huge parish of Nuestra Señora de Lourdes take turns staffing what Zwick describes as a "bed and breakfast." In Tecun Uman, there are two houses for people deported from Mexico, one for women and one for men built with help from the Scalabrini Fathers. In Mexico and Guatemala, the Oblate Sisters of the Most Holy Redeemer collaborate in the operation of the houses.

In Houston, Casa Juan Diego averages between 125 and 150 guests each day. It has a house for women and one for men and a dozen apartments for families of deported men, who were jailed for trying to enter the U.S. a second time or for a traffic violation.

"We have two clinics, one open two days a week and the other three days," Zwick says. "These are very important. The undocumented cannot get medication. They can go to the emergency room and the kids can go to school, but that is about the limit of services. We deal with a lot of people in the community who can't get Medicaid, don't have insurance or money to go to a doctor. Our medical care for the poor has increased markedly. We spend about $150,000 a year for medicine and prostheses for men who lost their legs jumping from trains.

"We need $2,000 a day just to survive," Zwick says. Some of the funds come from the 63,000 people all over the United States who receive the Houston Catholic Worker newspaper Zwick edits. But most of the funds come from the local Catholic community, Zwick says. The diocese allows the Zwicks to speak in three parishes each year. "A local family foundation gave us $10,000. The clergy, when they die, remember us in their wills. The Sisters of Charity also help us. There is a lot of help from all over. We can't complain about a lack of support."

The 1996 immigration law allowed the "expedited removal" (without a hearing before an immigration judge) of 76,000 asylum seekers in 1998. But refugees still come from all over the world and Annunciation House's Casa Vides, established to provide long-term housing for asylum cases, still has an average daily population of 20.

At an old hotel in downtown El Paso, the INS detains about 40 juveniles, generally between 14 and 16 years of age but some as young as 12, who have come by themselves. A recent class action suit has forced the INS to allow these youths, most of them from Central America, to live with relatives in the U.S. while their cases are adjudicated. Staff members of Las Americas interview each of these detainees within 10 days of their apprehension to see if there is a legal remedy. About 80 percent are eventually sent to live at least temporarily with relatives.

Planting seeds

As touching and inspiring as the work of the Simons and Veronicas is, it does not, after all, prevent the migrant and the immigrant from being condemned to the Way of the Cross. That is why many groups, including the ICIR, the Maryknoll Border Project, and Annunciation House, have consciousness-raising programs.

The ICIR gives workshops in parishes, churches, and synagogues. "We focus on the migrant face of God and we do theological-scriptural background on our call to welcome the stranger," Brother Dunn says. "The most powerful part is when participants share their own immigrant stories." These workshops are trying to change the notion that the migrant or the immigrant is an alien, a word often used to refer to a life form from another planet.

ICIR representatives have been urging INS officials to allow them to undertake human rights training for border patrol agents.

"They have been willing to start the process," Dunn says. "But I think it is going to take a few more meetings even to get them to agree on the curriculum. The negotiations are like the peace process in the Middle East."

Annunciation House focuses on the link between the miserable wages maquiladora workers get and consumerism in the United States. Garcia, who hosts about 15 delegations annually from universities such as Notre Dame, Georgetown, Colorado, Michigan, and Virginia, says, "Most come with the idea that the issue is immigration and how well the border patrol functions. Here they realize that the issues are much broader and complex. They leave with an intimate sense that the pair of shoes they are wearing has something to do with all of this and that they are not disinterested observers.

"I think we are planting seeds that later on are going to affect how people participate in society and will have an effect on legislation and policy."

One Veronica's conversion

Destroying the stereotypes Americans have of Mexicans is another challenge. "We Americans have the illusion that if Mexicans just worked a little harder and cleaned their houses better, everything would be fine," Tollefson says. Finding a different truth changed the life of Kay Spinella of Boerne, Texas and the other members of a five-family delegation that visited families in Juarez in a tour led by Maryknoll lay missioner West Cosgrove. "These families were working very hard," Spinella says. "They just weren't being paid enough."

The Spinellas had moved to Texas from Westchester County, New York, where they did not have a large house. Finding building costs much more favorable in Boerne, Spinella says she "got carried away." She and her husband built a house with four and a half bathrooms, a swimming pool, a hot tub, and five bedrooms-one for themselves, one for each of their three children (two of whom do not live there), and one for guests.

Six weeks after returning from Juarez, they sold the house and bought a smaller one. "I just couldn't live there any more," Spinella says. "I felt so greedy. Here we had three empty bedrooms, and the families we met in Juarez were living in one room."

Resolving not to forget what they had seen in Juarez, the five families formed a mission council in their parish, St. Peter, and persuaded their pastor, Father Tony Cummins, to start a sister relationship with Santa Maria de Los Angeles Parish in Juarez.

When Thanksgiving came, some of the families drove about 550 miles to Juarez to share their feast with families they met there. St. Peter's sponsors 30 students in Juarez, at an annual cost of $400 each, so they can continue their schooling beyond the sixth grade. When St. Peter's built a new church, it sent the old pews, baptismal font, and Stations of the Cross to Santa Maria. It also donated an ultrasound machine to the parish clinic.

Moreover, Spinella and another mission council member give classes in English as a second language to poor Mexican immigrant families in a mobile home park in Boerne. Spinella also organized a chapter of the Maryknoll Affiliates, people who do mission work in their own neighborhoods. The Spinellas are converting a stall in their garage into a room to provide temporary sanctuary to immigrants.

What may be the most important benefit, however, is the continuing dialogue and exchange. Nine of the Juarez scholarship students have visited Boerne and stayed with families with children their own age. The pastor of Santa Maria has visited St. Peter's several times and addressed the congregation. Mission council members visit the parish in Juarez at least twice a year. A sense of solidarity and friendship grows.

Perhaps the most thankless work on the border is the struggle for human rights, carried out principally by the American Friends Service Committee's border project, headed since 1983 by Roberto Martinez, a fifth-generation Mexican American.

With a small staff, Martinez documents abuses, talks to victims, monitors high-speed chases that have killed dozens and injured hundreds of immigrants, and brings violations to the attention of federal officials. On at least 10 occasions over the years he has received death threats from individuals or groups, including one from the Ku Klux Klan and a local militia.

Four years ago he was wondering how long he could endure. "But every time I ask myself why I am doing this, thinking that I have to get out, one more person comes in injured," Martinez says. "I see the pain and suffering and think I am not doing too badly. I just have to deal with the mental anguish.

There are so few voices out there to protect the immigrants. If I can do something to make their lives better, I should do it."

Martinez is still there fighting human rights violations. He says agents on the border often detain U.S. citizens who are Latinos, confiscating their birth certificates and sometimes actually deporting them. "I sent over 50 complaints to the INS and customs asking why they are violating the rights of U.S. citizens who are born here," he says. "This is racial profiling. There is a double standard of justice. We are considering a class-action suit."

Martinez and the other Simons and Veronicas would agree with the conclusion of the bishops' 2000 resolution on immigration reform: "At the threshold of a new millennium, our nation must revisit its historic roots and reexamine attitudes, laws, and policies toward newcomers who come to our land in search of a better life. We call upon all Catholics and citizens of good will to heed our Lord's call and challenge: 'For I was a stranger, and you welcomed me' (Matt. 25:35)."

Add comment