“It’s a weird job for a Jew in Tennessee, but somebody’s got to do it.” This is how A. J. Levine, a professor of New Testament and Jewish Studies at the Hartford International University for Religion and Peace, describes her 28 years teaching at Vanderbilt Divinity School. “I trained Christian ministers and religious educators,” she says. “I could not simply remain on the historical level of biblical interpretation. These are people who are going to teach and preach; they need the tools to get us from history to the present.”

Levine is the author or editor of dozens of books on biblical interpretation for both adults and children. She is also the first Jew to teach New Testament at Rome’s Pontifical Biblical Institute. Her most recent book is Jesus for Everyone: Not Just Christians (HarperOne), which builds on her experience teaching to explore how the gospels can speak to the pressing questions of our time. Each chapter lays out what Jesus says about a variety of topical issues, including economics, ethnicity and race, health care, family values, and politics.

“I kept getting asked these questions: Are we supposed to sell all we have and give it to the poor? What does the Bible say we’re supposed to do with our money?” she says. “[In my book] I look at the issues that have split families and communities today and that wind up being on the op-ed pages of our newspapers to answer what the Bible might contribute to the discussion. How could people who are preaching or studying this scripture do it a little bit more responsibly? And that happens when we understand Jesus in his own context.”

In your introduction, you list the people you hope will read this book, including atheists, Jews, Hindus, and Christians. Who is this book intended for?

My publishers initially wanted me to write a book called Jesus for Atheists, which I did. But when I sent it to them, they said, “We don’t like this.” And I said, “That’s OK; I really didn’t like it either.” I had spent a lot of time talking about why arguments for or against the existence of God don’t get us anywhere. Thinking about God is like thinking about love: If you’ve got it, you’ve got it, and you get it. But if you try to explain to somebody else why you’re in love with somebody, it doesn’t work.

So, we reconfigured this book, which made me happy.

I think Jesus was extremely wise. I have learned from him, and I want other people to learn from him. The stories that he told, and the stories that are told about him, can help us think our way through some hot-button issues today.

People outside the Christian tradition often don’t bother to read the Bible. But do you have to believe in Jesus as Lord and Savior to appreciate the New Testament? Absolutely not. One can look at the New Testament and appreciate it, and sometimes argue with it, without worshipping Jesus. I’m a perfect example of that. I’m a New Testament scholar, and I think Jesus is terrific, but I don’t worship him. Religious belief is something like love; it’s something that chooses you rather than something you choose.

So, belief is not the opposite of doubt. When the 11 disciples see the resurrected Jesus, the Gospel of Matthew says, “some doubted.” Even in the face of the resurrection, they’re not so sure about it, but they stay with the program anyway.

Faith doesn’t mean you just have to read the Bible and do everything the Bible says. It’s a matter of growing into the tradition. It’s not as if the church has been entirely consistent through its history. We did have that thing about whether everything revolved around the Earth versus the sun. That’s a good example of where people changed their minds.

If one claims to love the Bible or Jesus, one might want to know more about the times and the circumstances in which the Bible was written or Jesus lived. In the same way, if you fall in love with somebody, you want to know where they grew up and what their family was like. I want to know what life was like in Lower Galilee and Jerusalem in the early part of the first century because that helps me understand Jesus.

I’m not thrilled with the type of biblical studies that says, “We have a contradiction here between John and Mark, so clearly the whole thing is ridiculous.” No, we have four different perspectives of a story that cannot be told with a single perspective.

What are some of the things that we should know about Jesus’ historical context?

It’s common to hear in sermons and articles that first-century Jewish women were oppressed, and Jesus comes along and invents feminism. But if we look at Jewish women in the New Testament, we see that women have access to their own funds. When the lady anoints Jesus’ feet, that’s her Chanel she’s using. When the woman puts her two coins in the Temple treasury, those are her coins. When Martha welcomes Jesus to her home in Luke chapter 10, there’s no mention of Lazarus or indication that it’s his home: It seems as if she owns it.

We know that women have freedom of travel. Mary goes to visit Elizabeth. Women travel with Jesus. Women show up in synagogues, like the bent-over lady Jesus heals in Luke 13. And these women weren’t relegated to some separate balcony; synagogues in the first century didn’t have second stories. And women are not behind a screen, either. They show up in the Jerusalem Temple, like Mary and the prophet Anna at the beginning of Luke.

First-century Judaism wasn’t some sort of egalitarian wonderland, any more than contemporary America is. But women follow Jesus not because they’re oppressed but because, according to Luke, he heals their bodies and they are intrigued by his message. In other words, for the same reasons men follow him.

What are some of the ways that Christians abstract Jesus from his Jewish context?

Part of this happens because of Christology, or how someone understands Jesus in his role as an incarnate deity. Many people, even Christians, like Jesus, but they’re not really thrilled about the supernatural stuff. So they focus on his actions, making him the only Jew who cares about women’s rights or health care or the poor.

As a result, stereotypes start to show up. There’s an idea that first-century Judaism connected health with sin—people who were disabled were considered sinful. But the Jewish tradition had already decoupled those two things by the first century. Look at the book of Job: Job isn’t guilty of anything, despite his physical suffering.

When Jesus heals Peter’s mother-in-law, who has a fever, he doesn’t look at her and say, “what a sinful woman.” She has a fever, it happens. Most of the people who are disabled or suffering from some sort of ailment are embedded within family systems. They’re not cast off.

There’s also the idea that first-century Judaism was legalistic—which is always considered to be something bad. When Jesus says, “Love God, love your neighbor,” people think that means Jesus is light on the law.

But in fact, Jesus is pretty law heavy. He actually makes the law more rigorous. The law says don’t commit murder, which is a pretty good law. But Jesus says don’t be angry. He does what rabbinic Judaism calls “building a fence” around the law. You make a second law to make sure you don’t violate the first one. If you’re not angry, you’re less likely to commit murder. The law says don’t commit adultery, Jesus says don’t even think about it: If you don’t think about it, you’re less likely to do it. The law says don’t swear a false oath, Jesus says not to swear an oath at all.

Rabbinic Judaism does the same thing. What Jesus is doing is interpreting Torah, which every Jew can and should do. One does it in community, which is why Jesus debates with Pharisees about the law. If you don’t think something is important, you don’t bother debating it.

Christians love to contrast Jesus and the Pharisees. What do they often get wrong?

What do we know about the Pharisees? We know St. Paul was a Pharisee, and he’s proud of his identity. He describes himself as born “of the tribe of Benjamin, circumcised on the eighth day, as to the law, a Pharisee.” I have great credentials here, he’s saying. The other named Pharisees in the New Testament, such as Nicodemus in the Gospel of John or Gamaliel in the Book of Acts, are just lovely people. I would date them.

But there are these select comments from the New Testament, particularly in Matthew 23, which say “woe to you, scribes and Pharisees,” and for some Christians Pharisees have become the epitome of everything they don’t like.

I was part of a conference at the Vatican in May 2019 about the Pharisees—a conference that resulted in a book I coedited with Joseph Sievers. In an address for this conference, Pope Francis said to stop using the term Pharisee as a slur. We need to recognize that the Pharisees basically thought the same way Jesus did, which is why they’re so entangled in the gospels.

The Pharisees were out among the people. They weren’t some elite group sitting in ivory towers thinking they’re better than everyone else. Josephus writes that people actually listened to the Pharisees. They were living this simple life out among the people, they walked the walk as well as talking the talk.

In the Jewish imagination, the Pharisees are the ancestors of rabbinic Judaism. Jews see them as people who preserved the tradition and made it easier for folks to follow, who took away the authority of priests and made religion more egalitarian. They’re why we have Jews today, when there aren’t any Moabites or Ammonites running around.

The Christian imagination sees the Pharisees as forerunners of rabbinic Judaism, but also as hypocritical, misogynist, greedy, elitist. And that gets mapped onto Judaism.

I think it’s sometimes easier for a homilist to say, “Well, thank God we’re not like those Pharisees” than to wrestle with how to become better than we are. That’s what sermons ought to do: Yes, they ought to give good news and comfort, but they should also include a challenge to be better.

Can you give an example of one story from scripture that people often misunderstand?

The story of the Samaritan woman at the well in the Gospel of John is a popular one. In the story, it’s about noon, Jesus is tired, and he stops at a well.

Already the symbolism is overloaded, because John is pretty heavy-handed when it comes to symbolism. If you see running water, that means living water. You see light, that could be the light of the world. You feel a breeze, that could be the Holy Spirit. John’s taking us out of our mundane way of experiencing the world and pushing us into the transcendent.

In the previous chapter, Jesus and Nicodemus had a conversation at midnight. Jesus is the light of the world, Nicodemus is doing the best he can, but he’s in the dark. He doesn’t get it. The Samaritan woman shows up at high noon, so you know she’s going to get it.

When Jesus meets her, he says, in Greek, “Give me a drink.” It’s very abrupt. No, “Hello Samaritan lady, the weather’s nice today. Sorry about the difficult politics between your people and mine.”

But the woman remains cool. She says, “How is it that you are asking me, a Samaritan woman, for a drink?” And John slips in a note that Samaritans and Jews don’t have anything to do with each other, which suggests that the gospel is addressed to people who don’t know anything about Jewish-Samaritan relations.

But John often gives us some detail at the beginning that gets corrected at the end. Did Jews and Samaritans have anything to do with each other? Absolutely, because Jesus and this lady are having a conversation. What you see on the surface is not necessarily the truth—that’s part of how John’s gospel functions.

Then the two of them have a chat. Now, if you know anything about the Bible, you know that if a man meets a woman at the well, by the end of the chapter they’re going to get married. Or some marriage will be arranged: Abraham’s servant and Rebekah. Jacob and Rachel. Moses and Zipporah. Man meets a woman at a well, they get married.

Moreover, John the Baptist has already identified Jesus as a bridegroom. And the wedding at Cana takes place two chapters before this. John’s got me primed: I’m thinking weddings.

But John takes stories we’re familiar with and blows them up. So they start chatting. Sometimes readers interpret the woman as kind of slow. Jesus is talking about living water, and she’s asking, “Well, where are you going to get this living water? You don’t have a bucket, and the well is deep.” But she knows exactly what she’s doing. If you look at books like the Song of Solomon or Proverbs, this is really formulaic flirtation language. Readers would have expected this kind of banter. I think John’s original audience would be laughing, because they’re so familiar with the scene.

Many people today can’t imagine that Jesus had a sense of humor, but he had a fabulous sense of humor. I think one reason people were attracted to him is because he brought them in with smiles and welcome and humor.

So finally, Jesus says, “Call your husband.” She says, “I don’t have a husband.” And he replies, “Yeah, that’s right; you don’t have a husband, you’ve had five. And you’re currently living with someone who’s not your husband.”

We’re expecting an ideal Jewish virgin, but she turns out to be a multiply married Samaritan. So it doesn’t look like she and Jesus are going to get married.

How does missing some of the context lead to unhelpful interpretations?

Many commentators try to explain that the woman is the town slut. Or that the reason she’s at the well at noon is because she’s trying to avoid the other women who don’t want to have anything to do with her.

But that’s wrong. How do we know that? Well, she is at the well at noon, but that’s when Jacob meets Rachel at the well. It’s as if John is saying, “Please go back to Genesis and read the original story and see the interchange.” Jesus is, in effect, the ladder between heaven and Earth that Jacob dreamed about.

After their conversation, when she finally figures out what Jesus is talking about, she leaves her water jar at the well (this is symbolic, it represents her old way of thinking), goes back to the town and says, “I met this guy who knows everything I’ve ever done.”

If she were disrespected by the community, they wouldn’t have listened to her. They would have said, “Lady, come on, you know nothing. Go back to your lover.” But they pay attention. They must respect her.

Contemporary commentators will say, “Jesus didn’t condemn her. Isn’t that surprising?” But it’s not surprising when you realize that she wasn’t some sort of sexual pariah. There’s no reason to condemn her. Instead, she becomes the first successful evangelist. Good for her.

Today, we use the gospels to talk about all kinds of issues: guns and health care and women’s rights. Is this a legitimate way to interpret scripture?

The Bible is not an answer book or a Magic 8 Ball. But I think it is designed to help us ask the right questions and give us stories where these questions are raised. The scriptures of Israel have horrible stories about rape—how do we respond to them? Or about political figures who commit all sorts of personal and national crimes—what do we do with that? The text helps us think our way through things. The more immersed I am in the biblical tradition, the better I’m prepared to engage in contemporary debates that bring up these same questions.

Can we map Jesus’ teachings directly onto our society today? No. He doesn’t live in a participatory democracy, he lives in the Roman Empire. But there are questions that traverse the centuries. Issues of social inequality in Jesus’ time get us to questions of slavery or immigration today. Who’s in and who’s out? Who’s our neighbor and who’s not? How do we deal with our enemies? What should our sexual practices be? What should society allow and what should it condemn?

When the lawyer in Luke 10 asks who his neighbor is, that’s a really good question. That might lead us to reflect on issues of immigration and who’s in and out. How definitions of neighbors have changed over the centuries. Do we define the term ethnically or in terms of citizenship? In terms of religious belonging? The text opens up those questions, but it doesn’t necessarily answer them, because Jesus changes the question. At the end of the Parable of the Good Samaritan, he doesn’t ask, “Who’s my neighbor?” He says, “Which of those men was a neighbor to the guy who was robbed?” That may be a better question.

The New Testament and entire Christian Bible raise those questions, and even though the text doesn’t give us answers, it allows openness to alternative perspectives. It allows us to start having more civilized conversations where we weigh different options rather than just reacting to something quickly on social media.

This article also appears in the April 2025 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 90, No. 4, pages 16-20). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

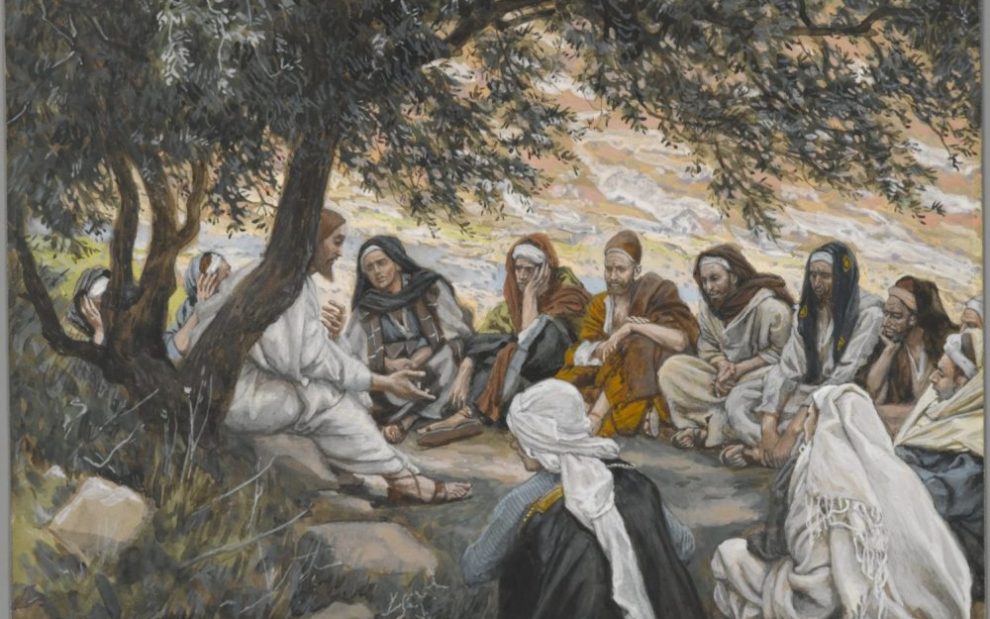

Image: Wikimedia Commons

Add comment