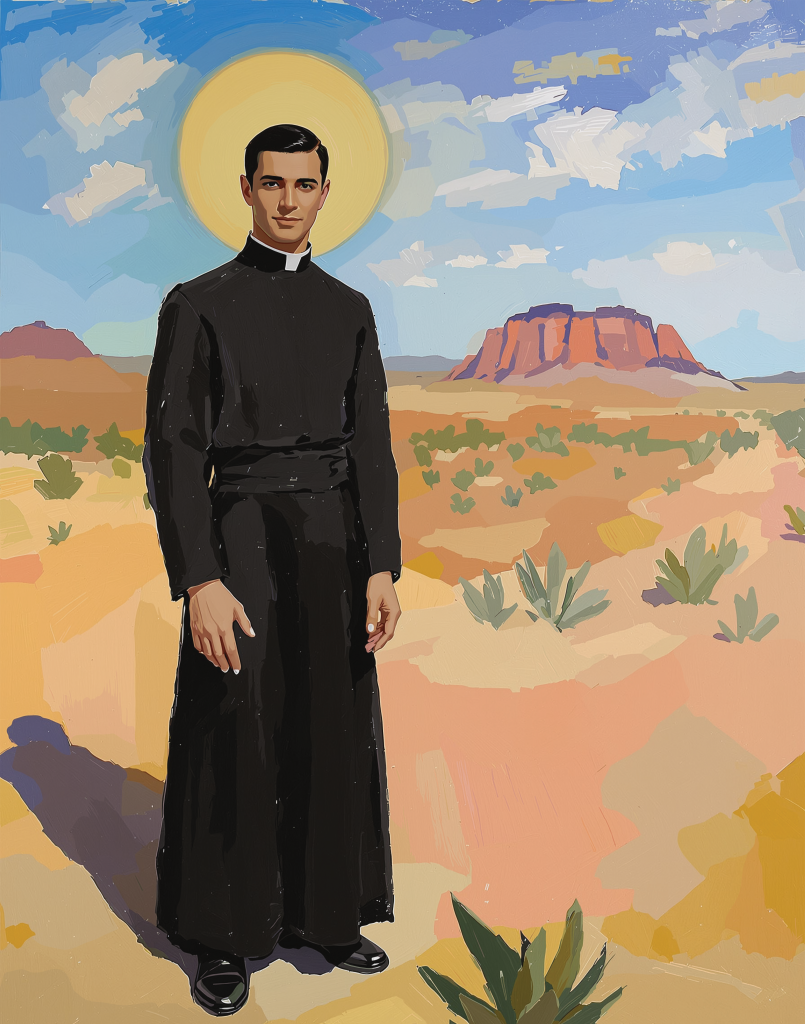

Over the past 30 years or so, several Mexican and American newspapers have reported cases of undocumented immigrants surviving the journey across the treacherous Sonoran Desert after receiving help from a priest in a pickup truck. He offers people rides and provides water, food, and money—often appearing out of nowhere. In return for his help, he asks people to visit him at his parish in the Mexican state of Jalisco. If they visit, however, they learn he’s been dead since 1928 and was canonized in 2000.

St. Toribio Romo, known as the Holy Coyote or smuggler saint, is “actually helping people cross the border,” says William Calvo-Quirós, a scholar of Latino/a studies, professor at the University of Michigan, and author of Undocumented Saints (Oxford University Press), a book exploring five folk saints, including Toribio Romo, who have connections to the U.S.-Mexico border.

Toribio sometimes makes migrants invisible to border agents, Calvo-Quirós says, and sometimes visits them in hospitals. Out of the five folk saints Calvo-Quirós explores in his book—Toribio Romo, Jesús Malverde, Santa Muerte, Juan Soldado, and Olga Camacho—Toribio is the only one who is canonized. The others are “folk saints” or “vernacular saints”—figures whom the church does not recognize, but to whom many Catholics and non-Catholics have devotions.

“Vernacular saints tend to be very pragmatic,” Calvo-Quirós says, as the main way they interact with devotees is by performing miracles. “It sounds kind of capitalistic, but if a saint does not perform miracles, if they’re unable to fulfill the needs of their constituencies and their market, they will disappear,” he says. “They need to be attached to a raw, primal need of a society or a community.”

Saints also adapt to devotees’ needs. Today, migrants are moving to cities and towns across the United States to take up jobs in meat packing, soy production, and corn production. “The border does not stay fixed,” Calvo-Quirós says. “The border is now in Chicago. The border is in Detroit. In Arkansas.”

Toribio Romo has moved to those places, too. He has relics in Chicago, Detroit, and Tulsa, and people in those cities have utilized his relics during protests for migrant justice, Calvo-Quirós says. In Chicago’s St. Agnes of Prague parish, the Society of St. Toribio Romo serves the needs of the immigrant community, including registering people to vote and engaging in other forms of mutual aid.

“Some people live in such vulnerable situations that the only way to keep going day after day is to invoke divine intervention,” Calvo-Quirós says. “If you are too rational, you lose hope and expectations that the world will change and that your life will get better for you or for your children. Saints can become a manifestation of God’s love for people, because they signify a different world is possible and change can happen.”

Folk saints of the U.S.-Mexico border

The U.S.-Mexico border is a “wound that is open and never heals,” Calvo-Quirós says, referring to a quote by Gloria Anzaldúa. Yet this “unhealed wound” is a site of resistance, community organizing, and emerging religious practices, he writes in his book.

Calvo-Quirós says folk saints can often take on multiple identities based on what devotees need. Jesus Malverde is most widely known as a “narco saint,” or informal patron of Mexico’s transnational drug trade, according to Calvo-Quirós. Busts and images of him are associated with drug trafficking—he appears in U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) training modules on drug paraphernalia, Calvo-Quirós writes. At the same time, however, he is a saint for immigrants crossing the border.

Juan Soldado is another folk saint invoked by those seeking to cross the border. But before he became the venerated Juan Soldado, he was a solider named Castillo Morales, and he is the primary suspect in the rape and murder of 8-year-old Olga Camacho in 1938.

Olga was “virtually forgotten until the early 2000s, when she reemerged as Santa Olguita, a feminist saint symbolizing the struggle against men’s violence against women,” Calvo-Quirós writes. “What can this story tell us about the connection between religion and violence against women along the US-Mexico border?”

In his book, Calvo-Quirós writes about prayer cards to Santa Olguita that women have begun exchanging: “Here, Olga comes back not as an innocent and vulnerable eight-year-old girl but as an avenger and seeker of justice for those most vulnerable in the region.” This Santa Olguita is an “active mobilizer for social change,” a folk saint who “understands the connections between urban violence and the physical and sexual abuse of women at the intersections of class and gender along the US-Mexico border.”

The stories of Juan Soldado and Santa Olguita, along with other women and girls like her, remind us that “we cannot continue living in a world that treats women this way,” Calvo-Quirós says.

The cult of another folk saint, Santa Muerte, is one of the fastest growing religious movements in the Americas, and she has become even more popular since the COVID-19 pandemic. Santa Muerte is a “skeleton saint,” a folk saint of death who is thought to work miracles for devotees, particularly for those seeking protection from death and who are looking for love, especially among LGBTQ+ people. Santa Muerte is not recognized by the Catholic Church—church leaders in Mexico consistently rebuke the devotion—and some consider her dangerous.

“The church says no to this devotion, but my experience with people is that they will go to Santa Muerte on Saturday, and Sunday morning, they will go to the Catholic Church,” Calvo-Quirós says. “In their mind and hearts, there is no fracture between one thing or the other; they are part of devotions people need in order to survive the difficulties of life.”

LGBTQ+ folk saints

For Emma Cieslik, a museum director, writer, and historian who studies folk religion and gender, folk saints are those who serve as “champions for the community, whether that be in conjunction with a struggle for power and liberation or with ethnic identity, racial identity, or gender identity—they are fighting for your rights and who you are,” she says.

Two years ago, Cieslik started the Queer and Catholic Oral History Project, where she records histories of LGBTQ+ Catholics. “A lot of people have expressed how specific Catholic saints, folk saints especially, have been important to their own personal development and identity,” she says. Folk saints allow many LGBTQ+ Catholics to find “pockets within church tradition where they could feel themselves being represented,” Cieslik says.

This includes St. Wilgefortis (whom Cieslik has written about for U.S. Catholic), a German princess who refused to marry the pagan king to whom her father had betrothed her. Wilgefortis prayed God would make her unattractive in order to get out of the marriage, and she then grew a beard. Her father was so angry with her that he had her crucified.

The Madonna of Montevergine is another LGBTQ+ saint whom Cieslik has written about. In the 1200s, she appeared to two men who had been attacked by local villagers for being physically affectionate, and Mary freed them by recognizing their love for each other.

Mary shows up to her people in many ways, Cieslik says. “Often as a result of religious syncretism, there are many traditions where ancient ancestral practices remained alive through images of Mary or folk saints,” she says. “Especially in Slavic regions, many folk saints, including within the Slavic pre-Christian pantheon, were folded into saints such as St. Gregory and figures such as Mary and Mary Margaret. They were a way that communities could keep hold of some of their ancient practices and ancestral knowledge.”

LGBTQ+ rights activists in Poland, where there has been an increase in anti-LGBTQ+ laws, often invoke the Black Madonna of Częstochowa, a beloved icon in Polish culture, Cieslik says. Activists have depicted the Black Madonna with a rainbow flag in protests.

LGBTQ+ folk saints are “evidence in the church that God and Jesus value and love LGBTQ+ people,” Cieslik says. “The important thing is that people can see themselves in these figures in the face of intense homophobia and transphobia from the church today.”

Kittredge Cherry, an author and minister, started the project Q Spirit, a website that includes the “LGBTQ+ saints” series, in which Cherry has documented more than 130 profiles of “religious figures with a queer side that has been hidden, and LGBTQ+ people whose spirituality is not well known,” she says.

“Finding LGBTQ+ saints means either queering the canonized saints or sainting the queers,” Cherry says. Officially canonized LGBTQ+ saints include same-sex pairs, such as Sergius and Bacchus or Perpetua and Felicity; gender-nonconforming saints such as Joan of Arc; “cross-dressing desert dwellers such as Marinos/Marina the Monk,” and more. Cherry also incorporates “modern folk saints who were LGBTQ+ religious leaders, theologians, activists, and martyrs who were killed for being queer,” she says.

An LGBTQ+ folk saint Cherry believes the Catholic Church will likely canonize is Mychal Judge, the gay Franciscan friar and chaplain to New York firefighters who died helping others during the 9/11 attack. Other secular figures turned folk saints include gay politician Harvey Milk, hate-crime victim Matthew Shepard, and transgender activist Marsha P. Johnson, Cherry says.

LGBTQ+ folk saints perform the “miracle of transforming shame into pride and self-hatred into self-esteem,” Cherry says. “In a world that often marginalizes LGBTQ+ people, we express our longing for justice and liberation through devotions to LGBTQ+ saints.”

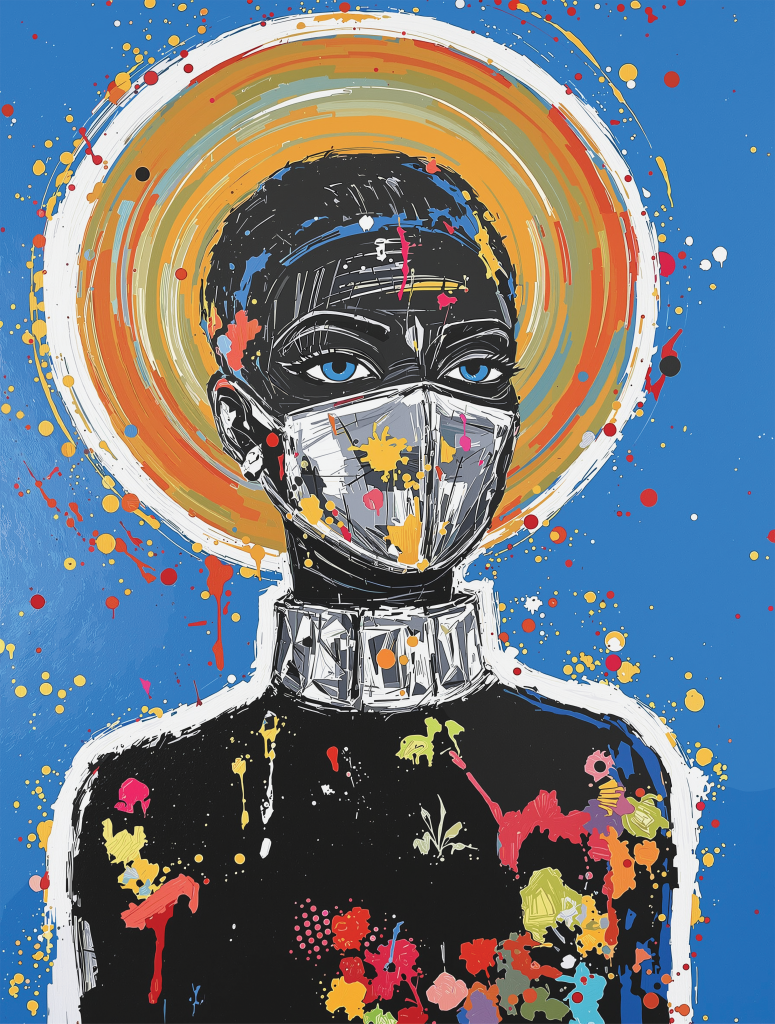

Anastácia and folk memory

Afro-Catholic and Umbanda Brazilians venerate a 19th-century enslaved African woman named Anastácia as a folk saint. Images of Anastácia often show her with a gruesome iron mask across her face, a torture device and symbol of the horrors of slavery.

There are different stories about Anastácia—one is that she defied an oppressive plantation owner and led a rebellion, thus was forced to wear an iron mask to keep her from speaking messages of liberation to others. Other stories say she was forced to wear the mask as punishment for speaking out against her rapist.

It’s unclear whether Anastácia started out as a Catholic folk saint or whether she came out of Umbanda, says Kelly Hayes, a professor and scholar of Brazilian religions at Indiana University. “There’s so much overlap between these things that to try to pinpoint it as one or the other, I don’t know if it’s even possible.”

What devotees across faith traditions tend to emphasize is Anastácia’s compassion and healing, Hayes says. “Her gaze is very important for people—she’s often depicted with green or blue eyes. People read that as a sign of her being mixed race. Some people say she was born in Africa, other people say she was the product of the rape of her African mother by a white enslaver.”

Anastácia’s legacy lived on in oral histories for decades. Then, in the 1970s, a traveling exhibit commemorating the abolition of slavery included a 19th-century drawing by a French author titled “Slave Punishment, Brazil” and depicting an enslaved person with an iron mask over their face. The image was widely “interpreted by people as an image of Anastácia,” Hayes says.

Between the 16th and 19th centuries, more than 5.5 million enslaved African men, women, and children arrived in Brazil—a system that was intricately tied to the brutal regime of slavery in the American South. Since possibly the 19th century, according to Marc Hertzman and Giovana Xavier in an article for Public Seminar, Black communities have revered Anastácia as a saint and people have called on her for strength and protection in hard times.

At the Church of Sts. Cosmas and Damien in Rio de Janeiro, Hayes says there used to be a tiled image of Anastácia at the very front of the church where people would leave offerings: ex-votos and retablos thanking Anastácia for her blessings. There was also a life-size statue of Anastácia in a glass case where people would leave requests for her intervention. “People petitioned her for healing,” Hayes says. “Lots of the things I saw in the chapel were thanking her for healing all kinds of things: illness, heartbreak, family problems.”

Eventually, the priest at the church decided that because Anastácia wasn’t an official saint, the church couldn’t display devotions to her. “This popular devotion to a particular Black female saint with a mask over her face—that gets reenacted in a certain way when the largely white male authority structure of the Catholic Church in Brazil decides that that’s not OK,” Hayes says. The church was also renamed.

In the 1980s, there was a campaign to have Anastácia canonized in the Catholic Church, but it was rejected on the grounds that there is lack of evidence Anastácia existed as a real person.

Today, Anastácia has become a figure of resistance, especially in Black women’s liberation movements, scholar Sarah Juliet Lauro writes in an article for Monument Lab, a nonprofit art and design studio based in Philadelphia. She is also a figure for Afro-Brazilian nationalism, Black history, and Black pride, Hayes says.

In 2019, artist Yhuri Cruz created an image of Anastácia without the iron mask, and this image has appeared on prayer cards, medallions, T-shirts, and in shrines, showing how Anastácia’s role as a symbol of empowerment is gaining more traction today, Lauro writes.

“Anastácia is a figure of incredible compassion, particularly for women,” Hayes says. “Any kind of gender abuse is one of her specialties [for intercession]. She also takes on some attributes of the Virgin Mary: incredible piety, purity of heart, love, and compassion amid suffering.”

The politics of canonization

Until the 13th century, there was no formal process for canonizing saints in the church—devotions sprang up in local Christian communities and were affirmed by local bishops, says Erin Rowe, a history professor at Johns Hopkins. Those devotions were passed down and over time became established practices.

In the high Middle Ages, the church became centralized and wanted to exert authority over canonization, Rowe says. In the 16th century, the church created the Congregation for Sacred Rites, which oversees canonization processes. Requirements for canonization remain the same as they did in the Congregation’s early days: a life of heroic virtue and demonstrable miracles.

Unsurprisingly, Rowe says, there are also political motives at play in canonizations. Throughout history, special interest groups have acted as lobbyists in Rome: mainly religious orders and wealthy kingdoms or nobility. Religious orders could claim more prestige if they had more saints. And the Spanish monarchy, for example, “pushed to canonize saints from everywhere in their empire,” Rowe says. “It tells us a lot about the geopolitics of a specific time, if you trace where the saints are coming from.”

Until the 20th century, there were relatively few canonizations. “If you look at the data, there may be like 15 [canonizations] per century,” Rowe says. “In the 17th century, Pope Urban VIII created what we call the 50-year rule: You had to be dead for 50 years before they could open a canonization process for you.”

But St. Pope John Paul II rolled back that rule in the 20th century, which allowed the canonization process to move much more quickly. “John Paul II himself is a great example; he’s canonized very quickly after his death,” Rowe says. “There were more people canonized under John Paul II than there had been during the previous four centuries combined.”

There was an effort by the church in the modern era to “bring forward candidates that came from more global backgrounds, because the majority of saints are Italian, and the vast majority of them are European,” Rowe says. “We see more saints from the Americas, for example.”

The church has always allowed a certain amount of popular devotion toward vernacular or folk saints, Rowe says, “but is very careful about it at the same time.”

For example, in the Middle Ages in France, a devotional cult sprung up around a dog—St. Guinefort, a greyhound who saved a child by attacking a snake and who was then killed by his owner, who mistakenly thought Guinefort killed the child. A shrine went up, and locals began to visit and invoke St. Guinefort for healing. The church began policing this devotion, claiming people were falling into heresy.

Mary and localized devotion

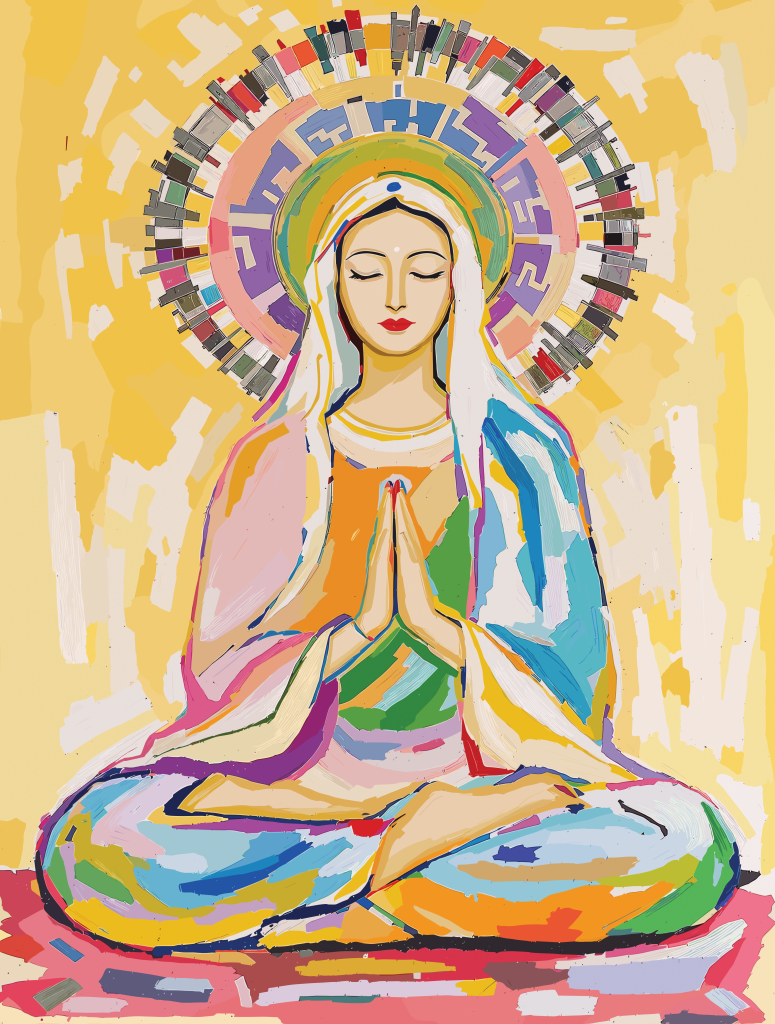

As with many folk saints, localized devotions to Mary reflect the hopes, desires, and needs of devotees. Michel Chambon, a cultural anthropologist and theologian based in Singapore, says Mary is a “universal religious figure” in Asia. “She’s venerated by many forms of religious traditions, with different levels of legitimacy: in Islam, Taoism, Hinduism, even Buddhism,” he says.

Chambon is a research fellow at the Initiative for the Study of Asian Catholics, which supports social science research into how Catholic communities across Asia have evolved.

Chambon studies how Mary takes different shapes across the continent and how these devotions reflect the social conditions and values of those regions and people. One of the largest pilgrimages to Mary in Asia is Our Lady of Velankanni (Our Lady of Good Health) in India, and most of the pilgrims are Hindu, Chambon says, which reflects how devotion can be tied to national identity rather than strictly religion.

In Singapore, Chambon says there’s a new Taoist movement that integrates all kinds of deities, including Mary. “We tend to reduce Mary to this universal appeal toward motherhood and femininity,” he says. “In the case of this Taoist movement, it’s not that. It’s Mary’s capacity to reach enlightenment, because she was meditating on everything in her heart and therefore she didn’t go through death. Which, for them, is proof that she reached enlightenment as Taoist immortals will do.”

In Japan, Taiwan, and China, “we see a strong coexistence between Buddhism and Mary, such as using a female bodhisattva to represent Mary,” Chambon says. “Catholics in Korea today depict Mary through Buddhist and animist art traditions. Mary is often a bridge between those religious traditions.”

Chambon says looking at how Mary is depicted and venerated invites us to consider our own images of Mary: “What are implicit cultural values about women, gender, and motherhood—which kind of mother are we longing for?”

In Japan, for example, the traditional notion of the father was as a “hardworking, distant parent,” and it was “women who were expected to provide emotional proximity; we find that in the way we represent Mary,” Chambon says. Whereas in India, “women are supposed to be the protecting, fighting parent,” and Mary is depicted that way.

Our Lady of Good Health is a “warrior fighter, fighting for you and expelling bad spirits. She is not just a loving, gentle, maternal Mary,” he says. Statues and art within people’s homes, as well as grottos in yards and street alleys, are other ways that folk expressions of faith come alive.

“[People invoke saints] because the world in which they live is not enough,” Calvo-Quirós says. “Saints are truly companions, because they help us to imagine the world, and even the church, differently.”

For many, devotion to folk saints is a matter of keeping hope alive. Their involvement in people’s lives testifies “over and over to people’s resilience in the face of adversity, exploitation, violence, and greed,” Calvo-Quirós writes in his book. These saints invite and inspire people to act, according to their own gifts and in their everyday contexts, to birth God into the world.

“In theology we call it sensus fidei, the collective sense of the faith,” Chambon says. “It’s not just something defined by the bishop or by theologians, but it’s a common sense of the real presence of God among us.”

This article also appears in the April 2025 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 90, No. 4, pages 10-15). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Art: Jory Mertens

Add comment