In the fall of 1981, something miraculous happened in the sleepy village life of Kibeho in the south of Rwanda. Alphonsine Mumureke, a young woman attending the local Catholic boarding school, heard a voice call out “my daughter.” The voice belonged to a woman, whose skin was neither black nor white, “of incomparable beauty,” as Alphonsine recalled, wearing a seamless white dress and a white veil, hands clasped in prayer.

“Who are you?” Alphonsine said.

The woman replied in the local language of Kinyarwanda:

“Ndi Nyina Wa Jambo,” she said. “I am the Mother of the Word.” That is, the Mother of God, the Virgin Mary.

Met with fervent skepticism at first, Alphonsine’s messages gained credibility in the coming year as others began to see the Virgin. Along with Alphonsine, two other young women would later be deemed credible by the Vatican—Nathalie Mukamazimpaka and Marie Claire Mukangango. Marie Claire had once been among the most vocal skeptics of Alphonsine, which made her conversion a strong argument for the truth of the apparitions.

As in many of her apparitions, the Virgin asked for repentance and prayer. But she had a darker message also. On the Solemnity of the Assumption, August 15, 1982, the three women all had a horrifying vision: a river of blood choked with corpses, decapitated heads, and unburied bodies left to rot.

The visions would continue until 1988. Then, in 1994, the Assumption prophecy seemed to come true.

In the span of a hundred days, at the direction of a Hutu-caste extremist government, almost 800,000 members of the Tutsi-caste—along with Hutu moderates and the Hutu spouses of Tutsis—were murdered. It was the complete mobilization of a society towards genocide, with family members, friends, and neighbors turning against each other. The courts, schools, and markets were closed “until the job was done,” the job being the extermination of Tutsis and the erasure of records of their very existence. Churches would become the most common site of massacres as thousands upon thousands flocked to them to safety, only to be betrayed, sometimes by clergy.

Prior to colonization, Hutu and Tutsi meant very little. Rather than a tribal or ethnic designation, these terms were instead, in the words of author Phillip Gourevitch, ”fluid descriptors of social standing, changing with acquisition of property or marriage into another family,” with Hutus being farmers and Tutsis cattle herders. The claim was that Tutsis were taller with lighter skin and thinner noses, whereas Hutus were shorter and darker with wide noses—but centuries of intermarriage put the lie to these stereotypes. There was a third group, the Twa, pejoratively called “pygmies” by Europeans, who formed an extreme minority.

As genocide survivor and author Immaculée Ilibagiza remembers, “[Hutus and Tutsis] had virtually the same culture: We sang the same songs, farmed the same land, attended the same churches, and worshiped the same God. We lived in the same villages, on the same streets, and often in the same houses.”

Before this, there had been a fervent sense of national unity, underpinned by loyalty to the monarchy. But Belgium, aided by the Catholic Church, sought to turn Rwandan society against itself, the classic divide and conquer. Colonizers favored Tutsis, claiming they were closer to Europeans than other Black Africans. The Belgians typically assigned Tutsi status to anyone owning more than 10 head of cattle. To circumvent the impossibility of telling apart Hutus and Tutsis on sight, Belgian authorities instituted identity cards with “ethnic” identity printed on them.

The fastest genocide in history did not come out of nowhere but out of years of escalating rhetoric and discrimination under the Hutu Power government. The Hutu Power movement, which began in the mid-20th century, unexpectedly embraced the notion that Tutsis were “different” and akin to foreigners. Hutus were true native Rwandans, whereas Tutsis were foreign. In 1992, one ideologue called for Tutsis to be expelled from Rwanda via the Nyabarongo, a tributary of the Nile. Radio Télévision Libres des Mille Collines (RTLM) was a putatively independent radio stationed based in the capital of Kigali that incited hatred towards Tutsis, calling them snakes or inyezi, cockroaches, part of a long-term campaign to dehumanize them.

These exhortations to violence led to mass death. On April 6, 1994, three days after Easter, Rwandan President Juvenal Habyarimana was returning from peace negotiations with Paul Kagame of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), a Uganda-based insurgent group of Tutsi exiles. The plane crashed under circumstances that remain disputed. RTLM put out the call for murder, even including the names and locations of those to be killed.

Thousands of Tutsis, along with Hutu opponents of the regime, flocked to churches for shelter. Because of its reputation for holiness, many thousands streamed into Kibeho, the site of the alleged apparitions of Mary. On April 13, a group of Interahamwe comprised of military, law enforcement, and civilians attacked the church, barred its doors, and set it on fire. Among those killed was Marie Claire Mukangango, one of the visionaries. The village became the base of operations for the killers, with approximately 28,000 being murdered in and around it.

While the church at Kibeho was set on fire, there was a chillingly similar, almost scripted pattern to massacre at other churches across Rwanda. Armed with machetes, Interahamwe proceeded methodically down church aisles and through rows of pews, hacking to death the hundreds or thousands huddled within. Even votive statues of Mary and angels were hacked apart with machetes because of their association with Tutsis.

It is important to note that this was not solely a Catholic phenomenon. Both Adventist and Anglican leaders were also involved—or allegedly involved—with the massacres. The whole of Rwandan society was reoriented towards genocide.

At roadblocks in Kigali, those whose identity papers revealed them as Tutsis were taken aside and murdered. There was gang rape of women as their husbands and children watched. HIV-positive men raped teen girls to infect them. Children were left alive with their limbs severed. Babies were thrown against rocks.Within the first month of the genocide, tens of thousands of bodies clogged the Nyabarongo River and Lake Victoria, seemingly confirming the “rivers of blood” prophecy of Kibeho.

The killing of Tutsis would only cease with the successful advance of RPF forces, led by Kagame, across the country, culminating in the capture of Kigali on July 4. But it was not the end of all killing. RPF forces unleashed violence of their own against Hutus, both prominent collaborators and refugees. At Kibeho, in April 1995, almost exactly a year on from the first massacre, there was a second: RPF soldiers killed 2,000 to 4,000 refugees, undeterred by the presence of peacekeeping forces.

The systemic promotion of hate using violent language, then calls for violence, then mass violence—such was the pattern in Rwanda.

The Catholics who participated in acts of genocide in Rwanda prioritized their group identity as Hutus over their identification in the Body of Christ. Catholics worldwide should be uneasy at even the slightest similarity to the hate-filled ravings of RTLM coming from our own, knowing that words can quickly become actions. Here in the United States, Catholics should be on guard when they hear, for instance, former President Trump’s description of immigrants as “vermin” who are “poisoning the blood of our country.” We must acknowledge that some of our prominent Catholic figures have used similarly inflammatory, dehumanizing rhetoric. Consider defrocked former priest Frank Pavone, who claims his political opponents are literally “allied with evil,” and Steve Bannon, who very publicly touts his conservative brand of Catholicism while calling for “political war” ending in “victory or death.”

But what of Rwanda? What of Kibeho?

Peace has come at the price of freedom. NowPresident of Rwanda for more than 20 years, Paul Kagame is dictator in all but name, but still receives accolades from the West for his policy of reconciliation. Of course, criminalizing the ‘propagation of ethnic divisions’ is a nebulous crime, perfect for ensnaring one’s political opponents.

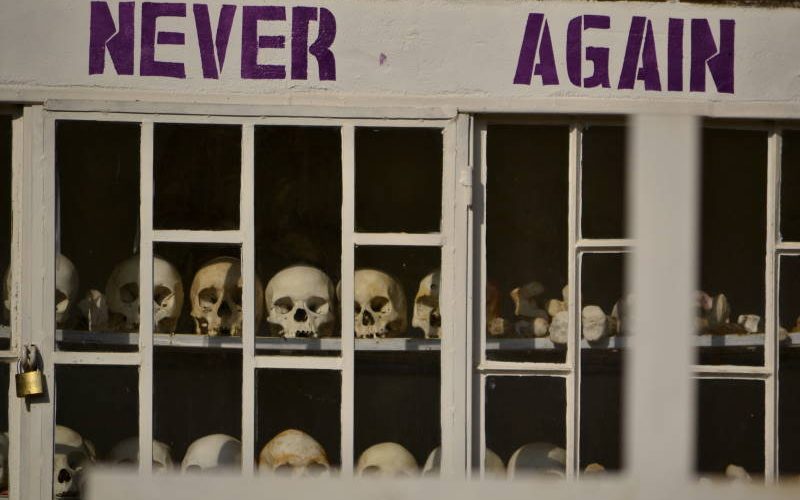

As for Kibeho, it remains a place of pilgrimage. Its bishop, Augustin Misago, who would later declare the authenticity of the Marian apparitions, was tried and acquitted for aiding the genocide, but questions remain about why he did not publicly oppose the killings. Today, a mass grave sealed with concrete and a shed full of bleached bones stand as monument to those killed in the first massacre by Hutu Interahamwe. There is no monument, no acknowledgement, of the victims of the later massacre by Kagame’s partisans.

Today, as we remember the genocide that occurred 30 years ago this year, Catholics around the globe ought to reflect on how they respond to hate and the propaganda that can spur on violence. In our increasingly polarized U.S. society and its reflected divisions within Catholic life, the need to moderate and evaluate such rhetoric is clearer than ever.

Image: Wikimedia Commons/Diego Tiria (CC BY-SA 2.0), display of skulls from victims of the Rwandan genocide at a memorial in Kibuye, Rwanda.

Add comment