I recently spent time in a cabin in the woods. For days I had to do things the “old way”; rustic was a repeated word in the brochure about this cabin, and they weren’t kidding.

Doing things the old way, as our ancestors did them, is how we often define tradition. It’s why we celebrate holidays like our parents did, prepare dishes our grandmothers made, or return to the same vacation spot by the lake year after year.

But that’s not how the church defines tradition. I like esteemed Jesuit preacher Walter Burghardt’s explanation best: Tradition’s not a museum piece, Burghardt writes, but the “best of our past, infused with the insights of the present, with a view to a richer, more catholic future.” Tradition, we could say, is our deposit of faith, with interest accruing across millennia for added value. We don’t simply hold onto what was. We also perceive what is and what must be to remain faithful to the message of Jesus now and for generations to come.

This month we celebrate the Solemnity of the Body and Blood of Christ, a sacramental reality at the center of all we hold true. Jesus said “take and eat,” and the church has been ritually doing this ever since. We do this in all kinds of ways. Formally, as at our first communion. Habitually, as at Sunday or daily Mass. With great intentionality, as in the viaticum we hope to be privileged to receive in the last hours of our lives.

We take communion in all sorts of frames of mind: thoughtfully, earnestly, piously, mindlessly. Sometimes we’re truly hungry for what the world cannot give as we stretch out our hands. At other times, we feel unworthy to approach the table. Or we may feel so “out of communion” with the church in seasons of our lives that we wonder if receiving the sacrament is hypocritical.

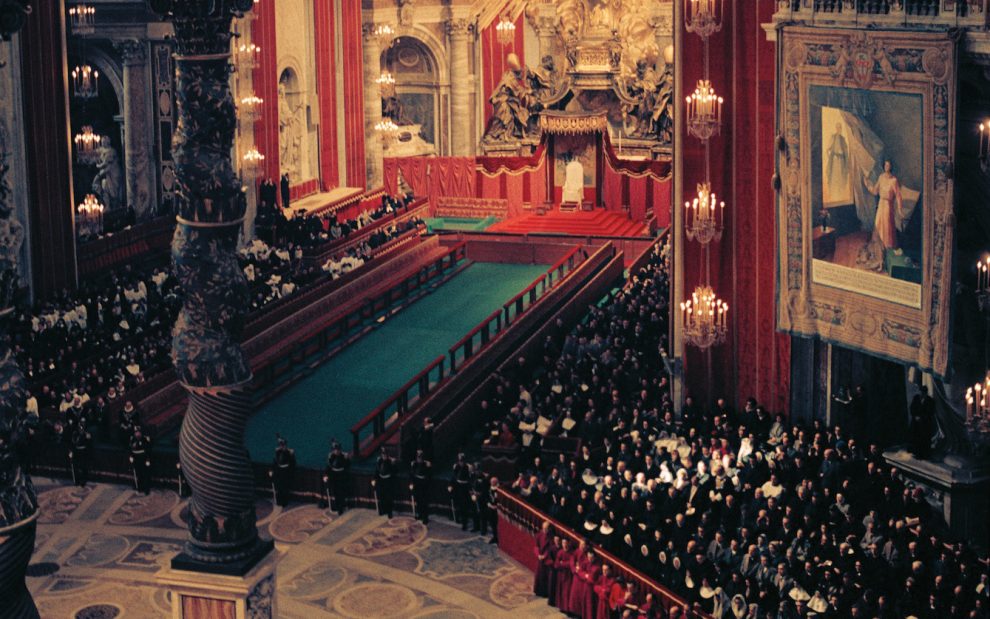

We Catholics perceive our identity as in or out of the church based on our relationship to this sacrament. Which brings us to the gravity of a document from the Second Vatican Council: The 1963 Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, or Sacrosanctum Concilium, isn’t just the first document produced by the council. It’s the one most popularly associated with Vatican II: the one that “turned the altars around” and translated the Mass into the language of the people rather than the formerly mandated Latin liturgy.

The contents of this constitution are the primary reason St. Pope John XXIII decided to launch the 21st ecumenical council in the church’s history to begin with. Throughout his priesthood and during his time as archbishop, it pained him that the Catholics he saw were so disengaged during Mass. Reading prayerbooks or saying rosaries as unintelligible rituals unfolded, folks in the pews rarely got up to receive communion, convinced of their unworthiness. What went on at Mass was too holy to comprehend and more than a little unwelcoming.

Yet the church taught that “full, conscious, and active” participation in sacramental life is the very heart of Christian life. Clearly, something had to change. What would it take for Catholics to become genuinely involved in the Eucharist and to understand themselves as the body of Christ, an incarnate sacrament delivered to the world?

Sacrosanctum Concilium, which means “sacred council,” kickstarted Vatican II with its call to invigorate the church, adapt to the times, and draw Christians closer together—all with an eye toward serving the world as Christ commissions us to do.

It was a big agenda. Not everyone was on board with the idea of aggiornamento, or updating church practice. Throwing open the windows of tradition to admit some fresh air seemed a public admission of error to those frantically seeking to keep them shut. Yet if we keep Walter Burghardt’s definition in mind, tradition has always snowballed down the hills of time, enlarging its capacity to bring the gospel to the ends of the Earth. Think about it: 2,000 years and 21 councils. Dozens of libraries’ worth of teachings. Laws written and rewritten. More than 10,000 canonized saints who each found ways to serve their time, place, and community.

Before celebrating in Latin, Catholics celebrated Mass in Greek. The only remaining fragment of that original liturgy is in our Kyrie Eleison. Jesus likely spoke in Aramaic at the Last Supper, which was the language of his community. Yet only a few Orthodox churches use that language now. What’s vital to preserve is our belief that bread and wine become the life of Christ for us. How we celebrate that reality has evolved across time. Why should it not continue to do so?

Liturgy is an action of Christ before it becomes an activity of the church, declares Sacrosanctum Concilium. Liturgy is the “summit toward which the activity of the Church is directed; at the same time it is the font from which all her power flows.” That is why, “in the restoration and promotion of the sacred liturgy, this full and active participation by all the people is the aim to be considered before all else.”

This meant that pastors, above all, had to reeducate themselves not only in how to perform the rituals but also in why they were being adapted. Seminaries had to be transformed, theologians retrained and reoriented in their purpose. Sacrosanctum Concilium didn’t just move altars around. Converting the liturgy required a conversion of mind and heart that reverberated from the Vatican to the last pew in the assembly.

Not everyone was prepared for this. Lots of Catholics, including some priests and bishops, headed for a theological cabin in the woods where they could cling to the old ways unchallenged.

Others remained to take up the weighty task of aggiornamento. New liturgy involved new media—and what would we have done without televised and live-streamed liturgies in recent years? New liturgy also required new music, sacred art, and catechesis. “Pastors of souls” had to instruct their people in thoughtful reconsideration of their roles in the church. Homilists found it essential to “promote that warm and living love for scripture” that became more accessible than ever, with much more of the Bible included in the revised lectionary of readings. Parish Bible studies were strongly encouraged to help Catholics become reacquainted with a sacred story from which they’d long been estranged.

New liturgical roles opened up. Permanent deacons were reinstalled for the first time in centuries. Lectors, eucharistic ministers, choir members, ushers, and greeters discovered or rediscovered places of significance. The assembly could no longer afford to be passive to the liturgy; more participation was required for the Mass to be properly celebrated.

The new rites “should be short, clear, and unencumbered by useless repetitions; they should be within the people’s powers of comprehension,” according to Sacrosanctum Concilium. Recent reforms of the lectionary and prayers have been somewhat less than successful in achieving these goals. So we keep trying. Because we can’t retreat to a cabin in the woods and still fulfill our commission to deliver Christ to every corner of the Earth. That’s our highest tradition, and it’s what makes us church.

This article also appears in the June 2024 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 89, No. 6, pages 47-49). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Lothar Wolleh, Wikimedia Commons

Add comment