A voice cries out:

In the desert prepare the way of the LORD!

Make straight in the wasteland a highway for our God!

Every valley shall be filled in,

every mountain and hill shall be made low;

the rugged land shall be made a plain,

the rough country, a broad valley.

Then the glory of the LORD shall be revealed,

and all people shall see it together;

for the mouth of the LORD has spoken.

This passage is an Advent classic. Found in chapter 40 of the book of Isaiah—and in our first reading this year on the Second Sunday of Advent—we hear a message of hope to a hopeless people.

I write this essay at a time when I, too, often feel hopeless. As a youth minister at a large congregation, I am continuously reminded that too many of our young people are experiencing mental health crises. I don’t need to read the statistics on record-breaking levels of mental illness, bullying, and suicide among children and adolescents; I see it every Sunday. One of these young people, at thirteen years old, just completed a stint in a psychiatric ward. Another is working hard to separate herself from a group of bullies at school. Some are grieving deaths or diagnoses of family members, and others are frozen by educational stress or existential anxiety about climate change. Outside my congregation, a young member of my spouse’s extended family just died by suicide because of middle-school bullying; I recently returned from visiting a dear friend in Tennessee who is mourning the death of a nine-year-old girl in her community, also due to suicide and probably abuse. Our young people are in a state of crisis, and it is hard not to feel powerless to intervene. I, and so many of us—young and old alike—are desperately in need of the divine hope promised in Isaiah.

Chapter 40 of the book of Isaiah begins what many scholars call “Deutero-Isaiah.” Most biblical scholars accept that what we know as the book of Isaiah is in fact three separate books written by three separate people living in different time periods and responding to dramatically different circumstances. Deutero-Isaiah was written in about 538 BCE at the end of the Babylonian exile, a period when the people of Judah (the Israelites) had been violently expelled from their land and held prisoner in Babylon. Deutero-Isaiah contains promises of redemption and return, beginning with these words of liberation and absolution:

Comfort, give comfort to my people,

says your God.

Speak tenderly to Jerusalem, and proclaim to her

that her service is at an end,

her guilt is expiated;

indeed, she has received from the hand of the LORD

double for all her sins.

What are we to do with these words of comfort? In my life, and certainly when I think about our young people, these hopeful verses feel so out of reach that they make Isaiah’s invocation seem insincere and out of touch with cold, bitter reality. Surely, to find comfort now would require turning away from the real pain of the world. Conversely, surely not turning away from the real pain of the world would make comfort impossible. How are we to live, sustainably, in this deeply wounded world? How are we to find comfort?

I return to Isaiah’s writing and remember his context: he was writing from within the Babylonian empire at the end of 70 years of Jewish imprisonment. Notice that Isaiah’s command is to prepare the way of the Lord in the desert, and to make straight God’s path in the wasteland. Take note: we are not to prepare the way of the Lord in lush oases, nor are we to make straight God’s path through fertile farmland. Rather, we are called to make way for God in the very midst of scarcity and risk.

Isaiah’s writing is sampled (much like a contemporary rap song would sample a classic track) in the first verses of the Gospel of Mark, our gospel passage on the Second Sunday of Advent. John the Baptist, cast in the role of the prophet in Isaiah as one “appearing in the desert,” preaches a gospel of baptism and forgiveness. And all the while, he tells his followers about an even mightier prophet yet to come who will baptize with the Holy Spirit.

While John might not have spoken explicitly of freedom, his audience knew oppression and powerlessness as much as their ancestors, the captive Israelites, had hundreds of years prior. Roman occupation and imperialism crushed the Jewish community, economically and religiously. Roman government officials, greedy for power and profit, kept Jewish life under their thumbs. When John echoed the prophetic message of Isaiah, he was talking to people who, like so many people around the world today, did not have the option of tuning out the world’s violence and pain. They lived it every day, and it impacted every facet of their lives.

So why preach a gospel of forgiveness—and not a gospel of revolution? I look back to the words of Isaiah, words of absolution: Israel’s guilt is expiated, and the debt of their sin has been repaid twice over. If I were a Jew living under Roman occupation, and if I believed my community’s oppression was the result of personal or collective sin, I, too, would seek forgiveness. I wonder today about the connection between forgiveness of sin and liberation. We have so many sins that need forgiving in our own lives: sins of power-hoarding and colonization, sins of war crimes and hostage-taking, sins of denying housing and resources and possibility to migrants fleeing violence and terror. If all of us, we who cause harm on many different levels, truly repented for our sins and were cleansed of our sinful instincts, how much closer would be our society’s liberation from injustice?

I think, too, about the word gospel—meaning “good news”—which we traditionally apply to the Jesus stories of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. John the Baptist, in the very midst of oppression and upheaval, makes way for Jesus, who is the ultimate Good News to the poor and suffering. In making way for Good News, John does not turn away from the hurt of the world: Instead of going to the more comfortable Temple with its authorized sources of power, he goes into the desert’s isolation, adapting to the rough diet and dress of a religious fanatic. But he does not seek the desert to escape the crises of his society. In fact, I would argue that John the Baptist could not turn away from the hurt of the world, because it surrounded him and his family and community and pervaded every aspect of their lives. In a similar way, many of our young people, both close to home and around the world, also cannot turn away from hurt and pain: they live with physical or sexual abuse in their homes; they face violence in the streets—or they live in a war zone or under a government that denies them basic human rights and dignity.

But what about those of us who can turn away? I, for example, in my privileged, upper-middle-class, largely white Midwestern neighborhood could delete my social media accounts, cancel my subscriptions to newspapers and journals, turn off the TV, and be blissfully ignorant of many of the more horrific events of our time. I often wonder what is gained by my personal awareness of atrocity and violence: Will justice come sooner because I, personally, watched the full video of someone getting murdered by police—or because I, personally, know the most current hashtags for a particular social justice cause? What is the benefit of spending my emotional energy bearing witness to the pain of people I will never meet? Isn’t it easier to just turn it all off and drink my peppermint mocha in peace?

I return to the witness of John the Baptist and the question of orientation, a question I bring to my own prayer frequently these days. While John the Baptist is fully in the desert, fully eating locusts, fully rooted in the discomfort of his Roman-occupied life, he is not oriented toward discomfort. He is not oriented toward violence. He is, rather, fully oriented toward the coming of Jesus. He is making way for Good News not despite pain and oppression, nor while being obsessed with it. Instead, as he makes way for Good News, he is oriented toward Good News, even amid the reality of earthly devastation and heartbreak.

Are we oriented toward pain? Are we oriented toward blissful ignorance? Or are we oriented toward the coming of Jesus, the coming of freedom, the coming of peace? May curiosity inspire us to ponder these questions about the orientation that guides our Advent journeys—and may we be empowered to share our answers with the people in our lives. This Advent and beyond, may we make way for Good News in the midst of the desert, in the midst of the wasteland. And may we nurture our young people, giving them deep roots in the wisdom of our spiritual ancestors, so that they may grow through and beyond the crises in their lives.

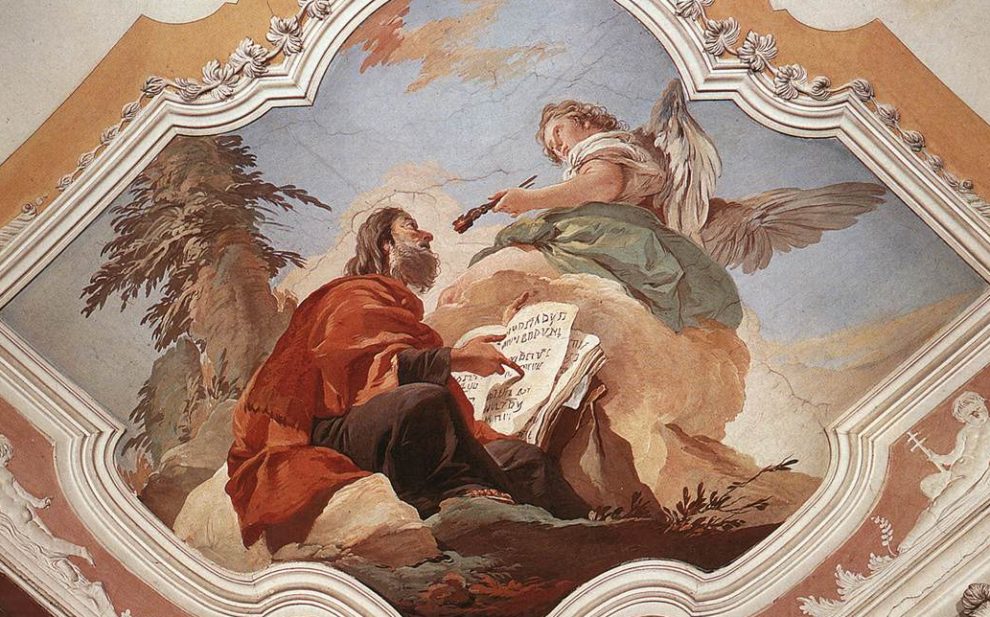

Image: Wikimedia Commons/Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, The Prophet Isaiah

Add comment