As an art critic and Catholic, I am often joyfully surprised by the unlikely homes of divine wisdom. St. Bonaventure wrote in his Legenda Maior that “In things of beauty, he contemplated the One who is supremely beautiful, and, led by the footprints he found in creatures, he followed the Beloved everywhere.” As St. Pope John Paul II indicated in his “Letter to Artists,” the artistic impulse is a reflection of God’s creative will. One such unlikely home of divine wisdom is the song “God Help The Outcasts” from the Disney version of The Hunchback of Notre Dame. Esmeralda, the “unclean” “gypsy” woman, enters the Cathedral Notre-Dame de Paris, and before a statue of the Madonna and Child, sings a song, entreating them to hear her prayer, even though she is an outcast. At first, she expresses her hesitation even to approach and speak to Jesus. But, looking at his face, she is compelled to ask: “Were you once an outcast too?”

Tradition responds to Esmeralda’s query with a resounding “yes.” Jesus was, and remains, an outcast. The gospels overflow with instances of Jesus being ridiculed, discredited, and of course, finally executed by the establishment, adorned with mocking attributes of his self-professed kingship. Pope Francis, in his 2014 Lenten Message, reminds Catholics that, “In the poor and outcast we see Christ’s face; by loving and helping the poor, we love and serve Christ.”

In the face of the institutional church’s infidelity to the gospel, such exhortations bring me great comfort. As a partnered gay Catholic, and a person of Latino descent who remains much separated from his ethnic roots, I often feel as though I belong precisely nowhere. When I navigate Catholic spaces, I wonder to whom I can come out; I fear that if I were to announce my relationship status to a priest, I might be denied communion. When I navigate queer spaces, or activist spaces, I utter the loaded word “Catholic” with much trepidation, lest I be called to account for my church’s sins. Yet I cannot possibly separate the two: my own marginalization and the formation Catholicism has given me to encounter the marginalized.

Reflecting on Jesus’ own suffering, his absolute loneliness on the incarnational path, is the nurturing water of my tormented faith. Esmeralda and her song remind me of a character from the gospels: the bleeding woman. Queer Catholics may often feel like both Esmeralda and the bleeding woman; as if we’re sneaking around a place we don’t deserve to be, just to touch Jesus, or if not him, at least his garment. I cling to the belief that when I go to Mass and receive communion, Jesus says “Who is it that touched me?” I hope that when I die, we meet and he says to me, “Daughter, thy faith hath made thee whole; go thy way in peace.” Although Esmeralda has some sense of herself as unworthy, she dares to go into the church, and she dares to approach and implore Jesus and his mother. The bleeding woman feels the need to be surreptitious, knows, as does Esmeralda, that she “shouldn’t speak” to Jesus, nor touch him. But she does anyway, and Jesus credits her for her own healing, testifying that she drew power from him. Crucially, Jesus seeks out the bleeding woman, dismissing Peter’s attempts to distract him. He seeks her out so intently that she saw “she could not go unnoticed” (Luke 8:47). It seems Jesus has an affinity for outcasts, because yes, he was “once an outcast too.”

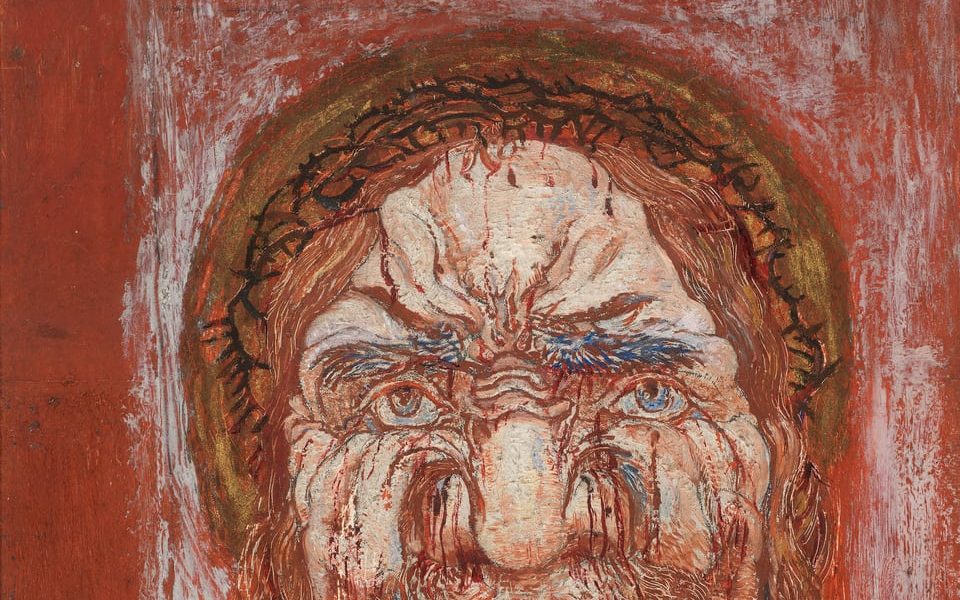

A more canonical representation of Jesus’ outsiderness is the lengthy iconographic tradition of the Man of Sorrows; images designed to portray the wretchedness of Christ, devoid of narrative setting. They are distinct from crucifixions, or pietas, or stations of the cross. They are simply portraits of Jesus, waist up, bearing the signs of his passion. Classical Catholic art is often compelling, beautiful, and blatantly homoerotic, but many of the Man of Sorrows images are repugnant and depict Jesus as markedly less pretty than we’re used to. They almost enlist us into the subjectivity of those who despised Jesus, who mocked him, and reviled him. They are representations less of triumphant sacrificial love, and more so of abject failure.

Perhaps better than any other iconographic tradition in the church, the Man of Sorrows reminds those who have been burdened with negative self-regard by hegemonic cultural forces that God incarnate was, in the words of Isaiah, “despised, and the most abject of men, a man of sorrows, and acquainted with infirmity.” A particularly challenging example is the Belgian painter James Ensor’s 1891The Man of Sorrows. Hardly the pearlescent and adorable Jesus which adorned my abuelita’s house, Ensor’s Christ is hideous and deplorable, bearing the marks of total anguish, affliction, and forsakenness. He is not serene, desirable, nor especially noble or long-suffering; he is disfigured by inconceivable physical and spiritual agony. This is our God: an ugly loser, an outcast, a persona non grata.

That is good news indeed. Good news not just for queer Catholics, but for all those to whom he is closest. Something we must cling to in the face of the irredeemable anguish in Palestine, and everywhere life is brutalized, profaned, and destroyed. For as Pope Francis says, “Christ, in his abandonment, stirs us to seek him and to love him and those who are themselves abandoned, for in them, we see not only people in need, but Jesus himself.”

The holiday season is notoriously difficult for queer people, but as Catholics we are comforted by the knowledge that Advent is all about loneliness, darkness, and waiting. Thus, we are sanctified by our isolation, made closer to our Lady and to our Lord upon his meager birth. Advent is an opportunity to be stirred by Jesus and his abandonment. To seek him in ourselves, and in others, to look for his image, to sift through our own imperfections and those of others in search of the Man of Sorrows in every person. The season is about waiting, an experience akin to faith, or “the evidence of things that appear not.” Waiting as our Lady did, wondering before God “how shall this be done?” yet still assuming her task, entrusting her welfare and that of her child to God, seeing within her own predicament that God “Hath filled the hungry with good things. And the rich he hath sent away empty.” We must proclaim the prophecy of our Lady, as we wait with her for the coming of Jesus: “Henceforth all generations shall call me blessed.” We must remember in our darkest moments that we “cannot go unnoticed” by our outcast God who loves us.

Image: Wikimedia Commons/James Ensor, The Man of Sorrows, 1891

Add comment