As a child, I visited the Civil War battlefield at Gettysburg. It was hard to imagine that peaceful scene—a lush, quiet field of gently waving tall grass—as the site of bloodthirsty ruin and suffering. But does a civil war have to be conducted with weapons on a vast battlefield, medics dragging off the wounded and the maimed? Could moving vans be the preferred weapon in a more civilized version of civil war?

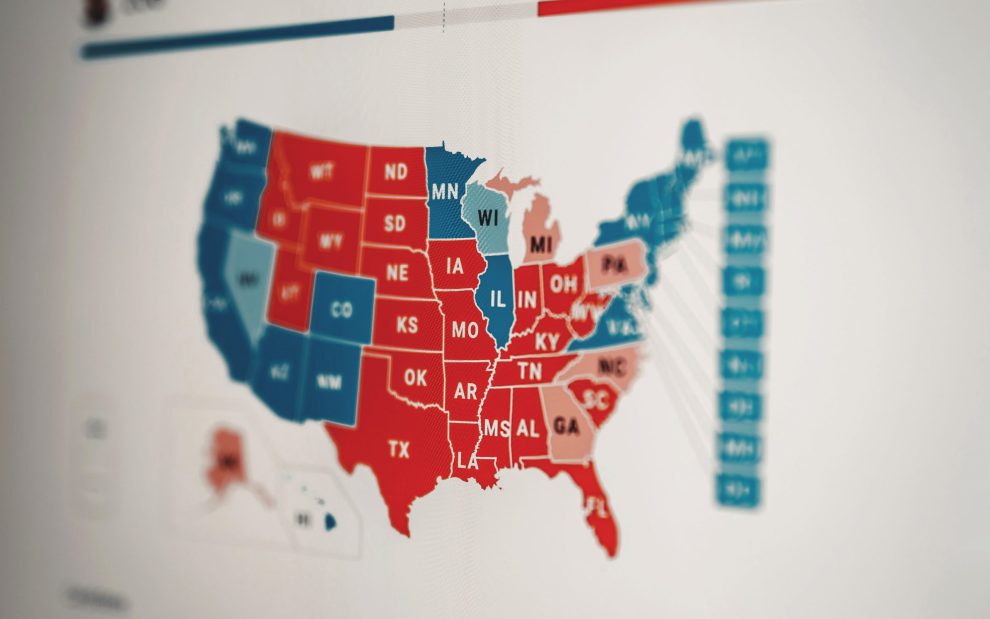

These days it’s not hard to silo yourself off from other opinions and perspectives via bespoke social media and news sources, but for some people even that rhetorical isolation does not create enough distance. Many of us are self-segregating by entire states as people on both ends of the political spectrum seek to live in places where they can speak their minds without fear of provoking someone with different social or political views. What sociologists call the “Big Sort” has been gathering steam as people relocate to states more amenable to their individual beliefs, divides deepening over politics and social issues such as abortion or LGBTQ equality.

The remote-work breakthrough engendered by the COVID-19 pandemic acted as a major accelerant of the Big Sort as more workers realized they no longer had to remain geographically tethered to a location they’d grown to find ideologically unfriendly. The United States’ federalized structure, which encourages the phenomenon, has been a strength except for those times when it contributed to breaking America down altogether. Are we heading, rapidly, toward such a time again?

The great social engines of solidarity—unions and religion—have faltered for decades as U.S. society has broken over identity, social mores, and diverging regional and economic interests. The coup de grace has been a culture of consumerism and social media algorithms more likely to provoke what my kids call “death scrolling” than Good Neighborism.

My father, a Korean War-era veteran who served in Germany, recalled how his army experience brought him into contact with Americans from all over the country. Shipped out of the Bronx to the South and West before finally being sent overseas, he met young men with different accents and attitudes who all learned to drink beer together in Europe.

That era’s obligation of national service had the practical effect of drawing at least some Americans together in an effort more important than their individual lives, regional conceits, and parochial perspectives. Perhaps today’s emergency of disassociation warrants the reimagining of a service-oriented national conscription that would reintroduce Americans to one another.

Those of us who are white Christians have special responsibility to respond to the breakdown in solidarity since much of it is driven by a blinkered Christian nationalism and nativist revival that has made U.S. political discourse toxic and dysfunctional. We may have withdrawn from difficult conversations with friends and family members, retreating into silence to preserve family comity. It’s time to accept some uncivil moments of tension and start talking again. We have to relearn how to disagree without assuming the worst of the people we disagree with, and we have to stop treating compromise as an inferior outcome.

The church should be a natural site of solidarity’s restoration. Its demographics and cross-continental reach make it one of the few institutions that includes just about every class, race, and ethnicity in the nation. Alas, its many self-inflicted wounds and its susceptibility to the same divisiveness roiling the U.S. body politic don’t offer much reason to hope just now. But we Catholics practically invented solidarity; as individuals and small communities of faithful we should commit a little time, creativity, and courage to grassroots efforts to restore it.

Read more Margin Notes:

- Catholic colleges have a chance to revive affirmative action

- Humankind’s legacy is shaping up to be a pile of garbage

- Solitary confinement is a form of torture

This article also appears in the October 2023 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 88, No. 10, page 42). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Unsplash/Clay Banks

Add comment