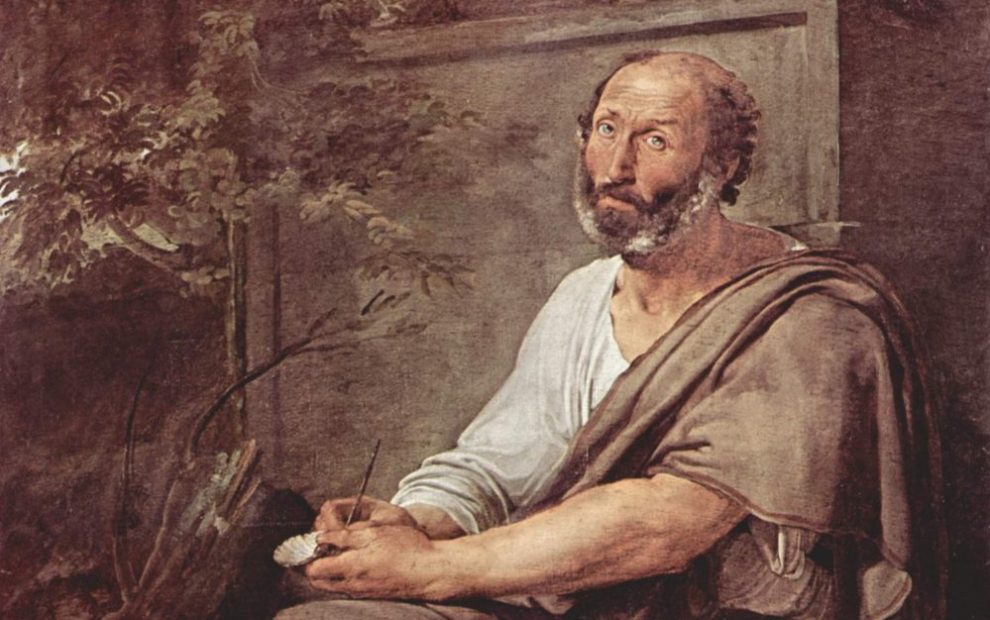

In my first few years teaching, as we read Aristotle’s view on friendship, I would ask my students to imagine how the Greek philosopher would evaluate the concept of “Facebook friends.” Fifteen years later, Facebook is no longer my students’ preferred social media platform; however, questions about the nature of friendship and community in an age of pervasive social media remain. How do we build friendship in a hyper-digital globalized world? Is our digital footprint helping or hindering building community?

For Aristotle, true friendship is a relationship of honesty, acceptance, and mutuality. In a relationship among equals, true friends love and accept one another for their own sake. It is not about competition or networking but rooted in virtue wherein we will the good for the other person, regardless of any benefit to us. Distinct from “imperfect friendships of pleasure or utility,” Aristotle believed true friendship was special and rare. Still, I imagine Aristotle’s shock at how rare friendship seems to have become. American society, notes Brookings Institution’s Richard Reeves, seems to be in a “friendship recession.” In 2021, the American Perspectives Survey found that 12 percent of Americans reported having no close friends, which is an exponential increase from only 3 percent in 1990.

Despite the ubiquity of social media and the language of connection, Americans struggle to build friendships. As a society, we are plagued by loneliness. In “Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation,” the United States surgeon general details the health effects of social isolation and lack of community connections. The decline in friendship correlates to declining health outcomes across the population. “Lacking social connection,” the health advisory notes, “can increase the risk for premature death as much as smoking up to 15 cigarettes a day.” Social isolation and loneliness have been publicly debated for almost 25 years, since Robert Putnam’s Bowling Alone (Simon & Schuster), yet the problem grows.

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated these trends, revealing our deep fragility. Researchers note that decreases in friendship during the pandemic were more prevalent among women as they took on greater caregiving responsibilities. Public health data shows that vulnerability to social isolation and loneliness is closely linked to other social and economic vulnerabilities. The elderly, those living in poverty, minoritized populations, and other groups who are marginalized in our society are at greater risk. Economic pressures often do not afford people free time to rest and socialize with friends. But I also find myself asking what role the Christian community plays in facilitating or hindering social connection.

Friendship is often neglected as a crucial element of human flourishing and the common good. We do not pay it enough attention in Catholic theology or Catholic social teaching. In Deus Caritas Est (God is love), the late Pope Benedict XVI wrote beautifully about eros and agape, but he left out philia or friendship. When scripture teaches us that “God is love” (1 John 4:8), it is agape, or self-gift, that we focus on. Yet, agape is not unrelated to friendship. For St. Thomas Aquinas, the goal of the virtue of charity is not just love of God or union with God but friendship with God. In John’s gospel, there is an emphasis on Jesus calling his disciples friends, not just followers or servants.

“Friendship is one of life’s gifts and a grace from God,” notes Pope Francis in Christus Vivit; “The experience of friendship teaches us to be open, understanding, and caring towards others, to come out of our own comfortable isolation and to share our lives with others.” As we look around our society, the epidemic of loneliness seems deeply connected to increasing violence, intolerance, and an inability to dialogue.

In Fratelli Tutti (On Fraternity and Social Friendship), Pope Francis emphasizes that “closed groups and self-absorbed couples that define themselves in opposition to others tend to be expressions of selfishness and mere self-preservation.” Friendship, the encyclical suggests, is tied to hospitality and our willingness to welcome others, as they are, into relationship. In hospitality, friends see and welcome us for ourselves not because we fit a particular use or need or because we conform. Do our parishes model and foster this friendship? Or have they become like closed groups?

Fear of rejection and making oneself vulnerable is a powerful barrier to friendship. So too is fear of change. But despite the risk, it is a gift. True friendship is incarnate. Even those lived digitally must be embodied because we as people are embodied. Friendships involve something shared, but true friendship does not seek uniformity but the good of each other. It is not anonymous but personal. Isn’t this also what the synodal process is about? Perhaps in learning to discern together as the people of God, we might also learn how to be friends.

This article also appears in the August 2023 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 88, No. 8, pages 40-41). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Aristotle, Francesco Hayez, 1811. Wikimedia Commons

Add comment