Los Quijotes, a San Antonio nonprofit, has been bringing free medical care to Mexico since 1989. The Sisters of Charity of the Incarnate Word have supported the group since its inception, and in 2015 Los Quijotes partnered with the University of the Incarnate Word (UIW) in San Antonio, the largest Catholic university in Texas.

Many of the participants see what they’re doing as following Jesus’ teachings. “Jesus served, right?” asks Rosa Ana Riojas, who has been volunteering with Quijotes for 30 years. “Jesus reached out to people who needed help. I think that what we do here is in that vein. Jesus was always reaching out to the underserved.”

The group has been going to Oaxaca during the first week of September since 1997. Oaxaca is the third poorest state in Mexico, one where 66 percent of the population are poor (earning less than $187 a month) and 22 percent are extremely poor (earning less than $133 a month). People that poor often can’t afford medical care. That’s why Quijotes chose to go there.

Quijotes partners with Mexican government officials, seven city and state health departments, medical students from the Universidad Autonomo de Oaxaca, and local medical personnel. “The two countries working together to provide medical care is just fantastic,” says Lety Vargas, the organization’s president. “We couldn’t do it alone.”

In 2022, 87 medical personnel, including faculty and students from UIW, made the trip. All medical personnel pay their own way.

Jovannah Ortiz took steps to prepare herself for the trip. “I did pray a lot,” she says. “I asked God to give me strength physically, because it’s a long week, and emotionally, because I’ll see things I haven’t seen before.”

Quijotes members went by bus from their hotel, the light bantering giving it the feel of a class trip. Each day started with a reading of a morning reflection, and Sister of Charity of the Incarnate Word Adriana Calzada Vázquez Vela read one from Ecclesiastes 3:1–8 on the first day. It begins, “There is a time for everything.”

“This is a very practical way to live the gospel,” Vela says. “Jesus was a healer, and that was his mission.”

Local governments choose the location for the clinics, and for the first three days it was in a community center on the outskirts of Oaxaca.

“This is a very impoverished area,” Vargas says. “There’s a lot of crime and delinquency here. But this is where we want to be. We want to be where the patients are.”

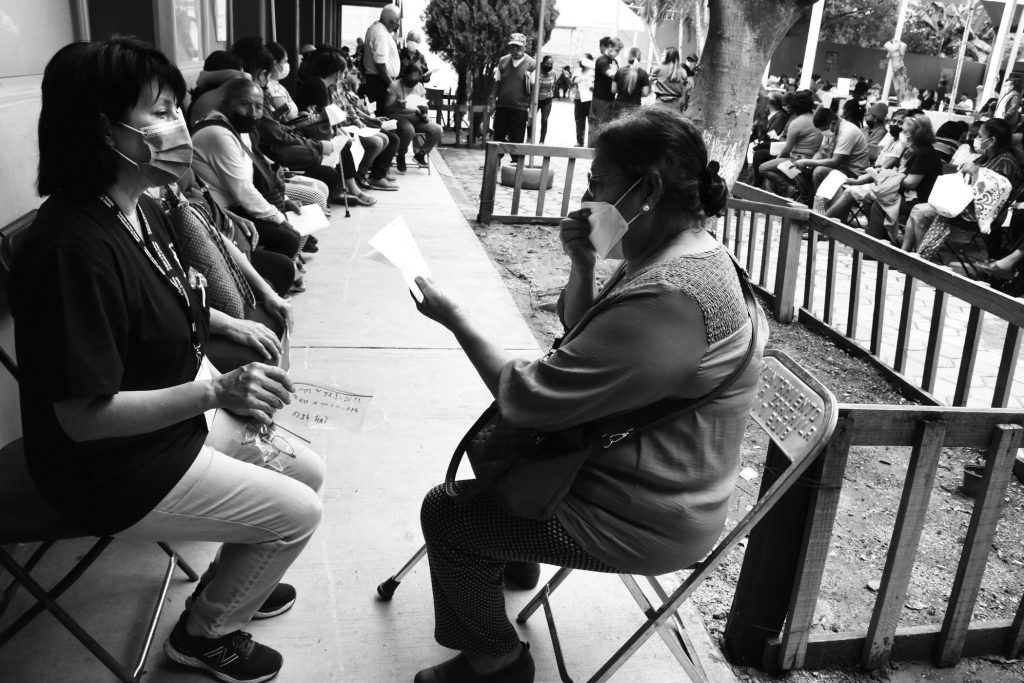

The first day started out a little chaotically. Dozens of people were already waiting as the bus arrived, and staff had to search for their examination rooms as supplies were unloaded. But doctors were soon seeing patients.

All patients first had their height, weight, blood sugar, and blood pressure recorded. In one room, 87-year-old Felipe Pérez waited patiently as his sugar was checked, his grandson at his side. “Sometimes we do not have the resources necessary to go to a doctor,” explains his grandson. “My grandfather has a doctor, but it costs.”

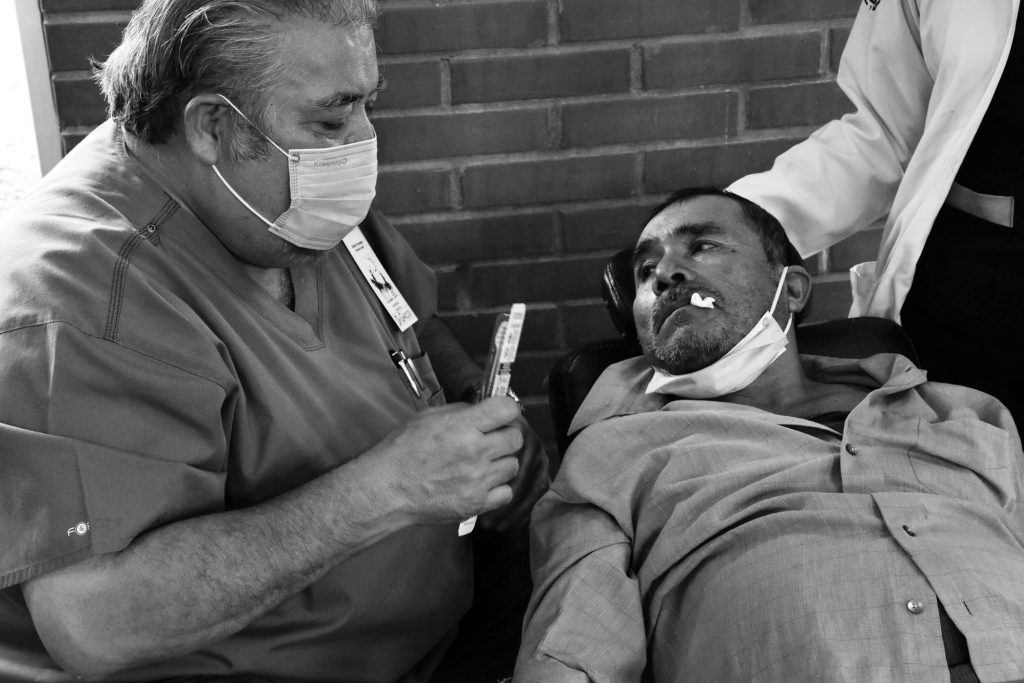

Dr. Marco Chalaby examined patients in one of the family medicine clinics. The majority of his patients were diabetic, which is no surprise since 16 percent of Mexicans have diabetes, and it is the number one cause of death in the country. “We counsel people, give them medicine, and send them to the dieticians,” he says. A devout Catholic, he’d gone to Sunday Mass at Templo de Santo Domingo, which he found inspiring. “Every profession has a gift, and it’s God-given,” he says. People are called, he believes, “to use your God-given gift.”

Ophthalmology was by far the busiest clinic. The majority of the patients Dr. Roger Velazquez and his team saw were also diabetic. “[Diabetes] can cause blindness,” he says. “Elevated blood sugars will damage blood vessels, especially in the eyes, which have the smallest vessels.” He was recruited by Quijotes’ president. “God was speaking to Lety Vargas to reach out to us, and we were looking to do a medical mission; it’s a match God made.” He says we all have a purpose in life. “Our purpose is to do surgery and help people live.”

Adjacent to the examination rooms, free glasses were being handed out. “People want to see, and because they can’t get care, they come here for help,” says Rachel San Martin, who has been volunteering with Quijotes for 25 years. “They can’t get care because they can’t afford it.” She was a blur of motion, hurrying between rooms and from one patient to the next. “I’m giving as much time as I can,” she says. “I feel a calling to help, to be involved. It comes out of my being a practicing Catholic. The idea is to give until it hurts. Physically, yes it hurts, but spiritually, I’m gaining.”

Juana Rojas, a 68-year-old Oaxacan, came to the ophthalmology clinic because she couldn’t afford new glasses. Dentists examined teeth, filled cavities, and fitted people with dentures. They also gave out information and toothbrushes. “People don’t know how to use toothbrushes,” says Dr. Javier Garcia. “They don’t go to the dentist because they don’t have money to go. Education is the biggest thing we do. This is a gift we’re giving. It’s like Christmas.”

After three days in the city, Quijotes went to Zaachila, a nearby pueblo, and set up in a primary school. Physical therapists treated patients ranging from babies who were a few months old to the elderly. In older people, says Dr. Matt Walk, “we’re seeing a lot of degenerative joint issues, a lot of knee and spine arthritis. These are occupational things.” They saw some babies with muscle weakness because, traditionally, babies are carried in a sling on a mother’s back. One baby examined by Dr. Monica Mendez had weak muscles on his right side. “It may have been that he was always positioned a certain way on the mother’s back,” she says. “We told her to switch sides when she carries him and to let the baby move on his own.”

Nutritionists were set up, appropriately enough, in the cafeteria. With diabetes literally a killer in Mexico, nutrition education is extremely important. “We try to teach prevention,” says Valeria Romo Nava. “We don’t tell people to avoid certain foods but to use proportions. The biggest problem is soda consumption, which is very high.” They were also combating misinformation. “One woman told me that her doctor said calcium wasn’t important,” says Dr. Beth Senne-Duff. “Of course calcium’s important.”

Beatriz Adriana Ambrocio Garcia says she benefited from the nutrition information she was given. “I need to eat more fruits and vegetables, less soda, less fats, less bread. This is all new information for me. I have to improve what I eat.”

Although founded by nuns and strongly supported by UIW, not all participants are Catholic—there are Episcopalians, non-denominational Christians, some non-Christians, and some who have no religion. Dr. Richa Garg, who practices Hinduism, has gone on five previous medical missions, including one that was also Catholic. “I was nervous at first, but there were no problems,” she says about that one. “We’re here to help regardless of religion. This isn’t about religion but about being kind and having a good heart.” Dr. Tarak Patel, who is also a Hindu, says, “Doing these things adds to your overall good karma. It makes you feel good, too.”

Dr. Roberto Fajardo is one of three staff entering and analyzing data. He runs a medical mission in Columbia but still decided to volunteer with Quijotes this year. “My job is to give back and help others,” he says. “Jesus taught that we need to take care of the least of us. That’s our job.”

Los Quijotes relies on donations and fundraisers to do their work. “All donations go to the project,” says Yolanda Pérez, the organization’s treasurer. “Nothing goes to salaries.” Pérez also helps with fundraisers and coordinates with Mexican authorities to get permits to bring in medicine. During her time in Oaxaca, she seems to be everywhere at once, signing people in, guiding patients to clinics, and answering questions. She also finds time to dance at the closing fiesta.

There’s a strong sense of community among Quijotes participants, and those who have come for years have formed lasting friendships. “We go out for dinner with people,” says Jim Stultz, who’s been coming since 1993. “Many have become very good friends now. I’ve gone to births, baptisms, funerals, weddings. These people have become family.”

For many, especially first-time participants, it is a moving and eye-opening experience.

“I saw a 73-year-old woman who had never been to a doctor,” says Nikkirose Angeles, a hint of incredulity in her voice.

“It puts things in perspective,” says Jovannah Ortiz. “I’m a completely different person. My outlook is different. I want to be more grateful for what I have. Now I count my blessings. It made me realize I have to thank God for the blessings I have.”

It is a long and busy week, with 400 to 500 people treated daily, but patients weren’t the only ones benefitting. “I’ve always felt like I’ve gotten more from people that I serve than I’ve given them,” says Riojas.

This article also appears in the June 2023 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 88, No. 6, pages 26-20). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Header image: Dr. Marco Chalaby examines a patient.

All photos by Joseph Sorrentino

Add comment